Glass_C10 - People at Creighton University

advertisement

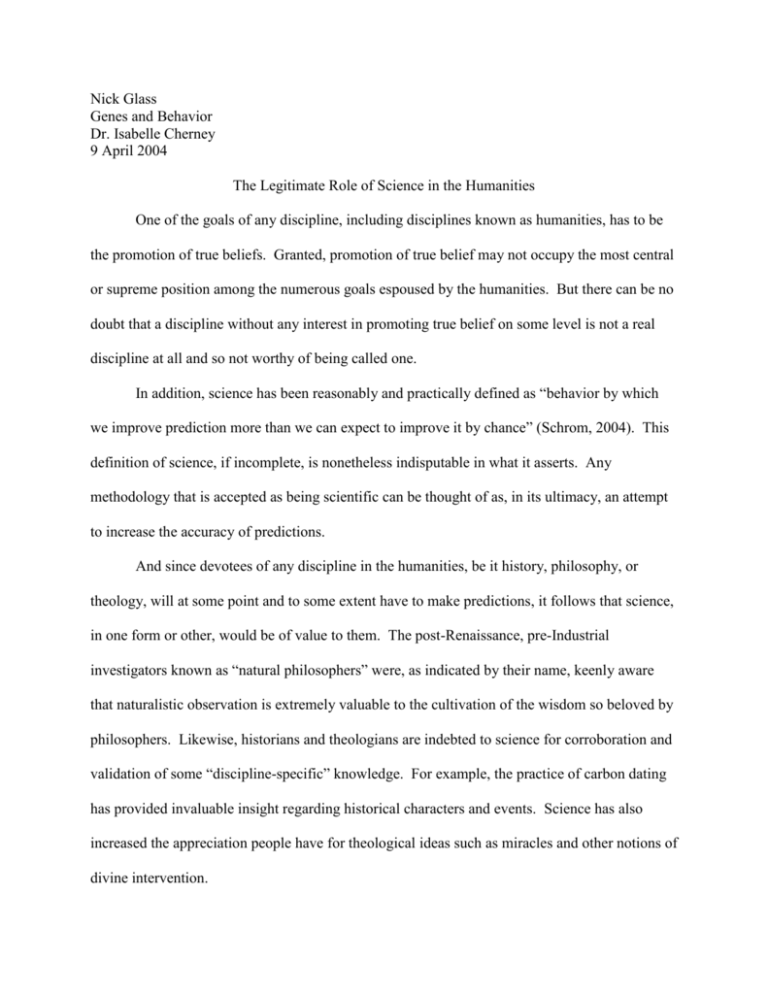

Nick Glass Genes and Behavior Dr. Isabelle Cherney 9 April 2004 The Legitimate Role of Science in the Humanities One of the goals of any discipline, including disciplines known as humanities, has to be the promotion of true beliefs. Granted, promotion of true belief may not occupy the most central or supreme position among the numerous goals espoused by the humanities. But there can be no doubt that a discipline without any interest in promoting true belief on some level is not a real discipline at all and so not worthy of being called one. In addition, science has been reasonably and practically defined as “behavior by which we improve prediction more than we can expect to improve it by chance” (Schrom, 2004). This definition of science, if incomplete, is nonetheless indisputable in what it asserts. Any methodology that is accepted as being scientific can be thought of as, in its ultimacy, an attempt to increase the accuracy of predictions. And since devotees of any discipline in the humanities, be it history, philosophy, or theology, will at some point and to some extent have to make predictions, it follows that science, in one form or other, would be of value to them. The post-Renaissance, pre-Industrial investigators known as “natural philosophers” were, as indicated by their name, keenly aware that naturalistic observation is extremely valuable to the cultivation of the wisdom so beloved by philosophers. Likewise, historians and theologians are indebted to science for corroboration and validation of some “discipline-specific” knowledge. For example, the practice of carbon dating has provided invaluable insight regarding historical characters and events. Science has also increased the appreciation people have for theological ideas such as miracles and other notions of divine intervention. So, properly understood, science does not threaten the humanities. And as long as scientists are not so hubristic as to consider science the pursuit of “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” (p. 3), but rather just the pursuit of physically observable and measurable truth, people in disciplines traditionally regarded as humanities will be more apt to acknowledge the usefulness of science in their pursuit of different kinds of truth (Kitcher, 1993). Moreover, people in the humanities and people in sciences should realize that their kinds of truth are complementary. This relationship is important in that knowledge of one kind fosters refinement to the approaches used in pursuing the other kinds. Thus, science should keep philosophers, theologians, historians, etc., honest, rational, responsible, and aware in their pursuits, while the humanities should keep scientists honest, rational, inspired, and curious in theirs. References Kitcher, P. (1993). The advancement of science: Science without legend, objectivity without illusions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Schrom, D. (2004). Can we use science to our own ends? Bioscience, 54, 284.