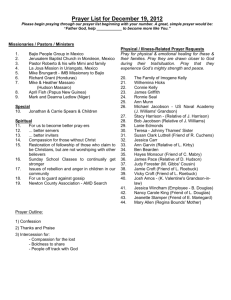

Tim-sermon-5-02-12

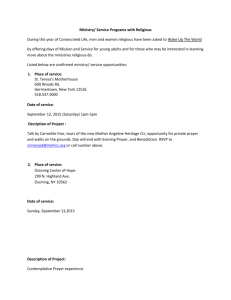

advertisement

Sermon, 5th February Mark 1.35-36 “Where shall the word be found, where will the word resound? Not here, there is not enough silence.” The world desperately needs contemplatives, and the world does everything it can to make contemplation impossible. We find ourselves surrounded by babble, rush, hurry, confusion, distraction, twitter. Our own desires and worries and fears are a constant stream of white noise. The body gets in the way. The mind gets in the way. Other people and their needs get in the way, as they do in today's gospel reading, and often they have every right to get in the way; even when what they do to the person who goes off to try and find some silence is “hunt him down”, which is what the Greek κατεδίωξεν means. Everything gets in the way. To such an extent that we may not even know, in the way of what exactly. In the midst of this chaos of noise, Jesus' command to us to pray can just sound like another piece of noise, another item to add to our daily task-lists under the “religious” sub-section. In fact his command to pray is the end of all task-lists, liberation from the task-list, the release of the oppressed spirit from its burdens. And that we should pray is not, or not just, a religious or spiritual necessity; it is a natural necessity. Our secular century has thrown out many babies with much bath-water, and one of the most important is the idea of prayer, the idea that every now and then—ideally, perhaps, at least once a day, in the morning—we should sit still and try and get some perspective, try and get a grip on where we really are in life, what matters and what doesn't, what's valuable and what isn't, what is worthy of our awe and reverence and what isn't. Unless we do this, and do it fairly regularly and fairly effectively, there's a danger for each of us of ceasing to be clearly an individual person at all. Despite what the philosopher David Hume seems to have thought, an individual person is not just a bagful of conflicting desires and fears tugging in all sorts of different directions, pulling the body this way or that according to their relative strengths. There is more to me than a parallelogram of forces. What makes me a single person is my ability to unify myself: to step back from the forces in my psyche and evaluate them. By choosing between the desires and the fears, the imaginings and the valuings, that I find inside me, I come to be able to develop a clear plan for my life based on whatever I find most valuable; and that plan gives me the unity of a person. But in order to do this, I need to be able to concentrate and focus my attention; I need to be able to make my mind a single thing, not just a bag of ravenous conflicting urges. This ability to unify my own mind is what prayer is, or part of it, and it isn't just for believers; it's for everybody. Above all things what human beings need is clarity, focus, the ability to unify our minds around some one object of steady and still attention. “Purity of heart,” as Kierkegaard famously said, “is to will one thing.” Without a clear and simple sense of reality as the basis for everything else we do and think and are, there is no happiness for us, quite apart from whether we believe in God. Without that anchor, we are ships that drift, both in our personal choices and in our moral values. Many people today would scoff at the idea that there is any connection between religion and morality—“you don't need God to be good”, they will rather dogmatically tell us. But one central part of the religious outlook on life that they seem so desperate to reject is this idea of centring down in prayer, of starting everything you try to do in a place of stillness and peace. I don't believe that anyone can do anything really valuable without that contemplative starting-point. But so far as I can see, the idea of beginning action in contemplation is not just not dominant in modern secular thinking about ethics. It's completely unknown, and completely against the spirit of that thinking. Prayer is contact with and reflection on reality. People sometimes describe prayer as escapism, and how ironic is that? The Buddhists would say that what is unreal is the constant round of striving, coveting, envying, ambition and contention, self-aggrandisement and self-promotion, worries about what others think of me, pointless fears for the future, empty regrets about the past... and all the rest of the tide of pettiness that the world and our own egos try to drown us in. And the Buddhists would be right. National Lottery Live, what A said to B about C, whether people think I'm amazing, who is dating whom in Hollywood, the contents of your email inbox, 95% of what you see on the internet and the telly and in the newspaper: that is unreality. What prayer forces us to do is focus on the real reality. This focusing is hard work, and it is difficult, because—to quote another well-known line from T.S.Eliot—“humankind cannot bear very much reality”. Facing up to where we really are is hard. Just for me to sit still in my own presence—never mind God's—is hard. People sometimes say that prayer, or church, is boring. There are many ways for prayer or church to be boring, and not all of them are good; yet a certain kind of boringness is not unnaturally part of prayer, and therefore of church, since church is mainly about prayer. (What else are we here for? The jumble-sales? The custard creams? To keep our toes warm? I don't think so. We are here to pray.) Prayer is a journey of exploration, and I don't expect every moment of the journeys of an explorer like Christopher Columbus or Fridtjof Nansen was rapturous excitement. To pray well we have to learn to cope with silence and quietness, and that can be difficult when everything in the society around us seems to be based on a pathological terror of silence, on a determination to do anything at all sooner than face up to the reality that we run the risk of becoming aware of, the moment we shut up. Prayer begins in reverent attention to something that isn't yourself. It begins when you concentrate on something beautiful that lies beyond your own petty concerns, something perhaps that is quite irrelevant to them, and are caught up in self-forgetfulness because you are focused on that. All you can see is the beautiful picture, or the image of someone else's generosity to someone else, or whatever it may be that you're focusing on. And this attention to something other than yourself has set you free from what Iris Murdoch called “the fat relentless ego”: it's enabled you to get beyond yourself. There is a curious paradox in the fact that the only way for us to make sense of ourselves is for us to learn to forget about ourselves and start focusing on something else. But like many other paradoxes, this one is true. Prayer in this sense of self-forgetful, detached contemplation is obviously not just a religious activity. It's a natural one, an activity that anyone at all is better for engaging in, no matter whether they believe in God; and it's an activity that our society is desperately in need of. But of course, as a Christian, I also think that there's a reason why prayer is a natural activity for us humans: it's natural for us because we are naturally drawn towards reality outside ourselves, and the ultimate reality outside ourselves is God. Anyone at all who seriously engages in contemplation of the sort I've described will be enabled, in time, to get beyond his own “fat relentless ego” to the beauty of the world around us that selfishness hides from us. But I think it's also true that that beauty has a heart and a direction to it; prayer brings to us a kind of liberation and a kind of grace, and that liberation and grace are no accident—they come to us from God. The beauty of reality leads us not only beyond our greedy, fretful self-absorption to actual contact with the people and the world around us; it also leads us beyond that, to actual contact with the one who is himself the source of all reality and the source of all beauty. If prayer is a journey, it's only because there is a God to pray to that the journey can even begin. This is why what should we do when we pray is what the old man said he did, when the vicar asked him curiously what he spent so much time doing before the altar. In the old man's words: “I look at him, and he looks back at me.” A question about today's reading. Where had Jesus got to in the prayers that Simon and the others interrupted when they finally “hunted him down”? We can't say, of course, but from elsewhere in the gospels we know Jesus' own outline description of what prayer should be. A modern newspaper advertisement might call it “Five easy steps to psychological health”—and if it did, the newspaper would have something true and worthwhile in it for once. As a frame to direct and discipline our own wandering thoughts when we try to engage in contemplation, there is nothing better than the Lord's prayer. We begin with God's supreme majesty, the utterly transcendent and inaccessible in-heaven-ness of the one who is also, amazingly enough, a father to us. We speak out our own need to recognise that he is holy, and the desperate longing in our hearts that, did we but know it, is actually a longing for the justice of his kingdom and the fulfilment of his will, in this messy world just as in the perfection of his paradise. We tell him our own more mundane and basic needs: above all to be fed, to be forgiven, and to forgive. We ask him not to make the way that he puts before us impossibly hard— knowing that he will never make it impossibly hard, though our Father has never promised us that our way will be easy, any more than he promised that to Jesus. And lastly we ask him to deliver us from the aimless malice of others, and even more importantly from our own aimless malice, knowing full well that he already has done, and always does now, and always will in the future, because his is the kingdom, the power and the glory—for ever and ever. Amen.