Models of Skilled Single Word Reading

advertisement

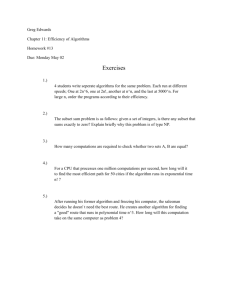

(Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 1 Reading In this lecture we will discuss how people read single words. We will concentrate on the processes that take the reader from print to sound and will not consider issues involving units larger than a single word. We will consider how evidence from normal adults and those with acquired dyslexia can inform models. We will also think about how children learn to read. 1 Skilled Single Word Reading The models discussed here apply mainly to English but may also be extended to other alphabetic scripts. As skilled readers we are able to read all sorts of words. We are able to read non-words such as ‘bork’ or ‘fass’ and words that we have never seen before. This would imply that we are sounding out words, assigning a phoneme to each grapheme. However, this does not account for our ability to read irregular words such as ‘pint’ or ‘yacht’. If we always read through sounding out then we would regularise the pronunciation of irregular words; this clearly doesn’t happen. Models of reading must account for our ability to read these two different types of words. 1.1 The Dual Route Model (Coltheart et al) The dual route model deals with non- and irregular words by positing two independent routes leading from the printed word to sound. 1. The Direct Access route This route is also known as the lexical route and accounts for the pronunciation of irregular words.. In this route, reading must proceed through the lexicon as we need information specific to individual words in order to pronounce them correctly. This route can also account for the correct pronunciation of homographs (e.g. ‘tear’). 2. The Grapheme-Phoneme Conversion route (GPC) This route is also know as the non- or sub-lexical route as reading proceeds without access to the lexicon. Each grapheme is assigned a pronunciation by mapping to a phoneme. This route accounts for the pronunciation of new or non-words by phonological recoding. Printed word LEXICON Pronunciation Simplified Dual Route Model GRAPHEMEPHONEME CONVERSION RULES (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 1.2 2 The Evidence from Normal Readers: 1.2.1 Real Words The dual-route model suggests that all real words both (irregular and regular) should be read by accessing the lexicon. 1.2.1.1 Regularity effects A robust finding is that the regularity of a word affects the time it takes to name it. For example a regular word such as ‘wave’ is named more quickly than an irregular word such as ‘have’. There is also an interaction with frequency. High-frequency words are relatively unaffected by regularity but low-frequency words are highly affected 1.2.1.2 Neighbourhood effects Glushko (1979) demonstrated that it is not just the regularity of the presented word that affects reaction times but also the regularity of the word’s neighbours. Some regular words have neighbours that are also regular. These words are consistent. Other regular words have some neighbours that are not regular. These words are inconsistent Regular consistent: MADE (GRADE, JADE, FADE) Regular inconsistent: WAVE (SAVE, BRAVE, GAVE… but HAVE) Glushko found that inconsistent words such as ‘wave’ are named more slowly than consistent words such as ‘made’ even when these words are of similar frequency. Sometimes regular words are given an irregular pronunciation. 1.2.1.3 Conclusion: A simple dual route model is not sufficient to explain these findings. The dual route model would predict that all real words should behave in a similar manner since they are all read by the lexical route. However, we find that reaction times are affected by regularity, frequency and consistency. 1.2.2 Non-words The dual-route model predicts that all non-words will be read by the GPC route. There are, however, a number of problems with this suggestion. 1.2.2.1 Pseudohomophones Pseudohomophones are non-words which sound like real words when they are spoken e.g. brane. These words are named faster than other non-words but are rejected more slowly in lexical decision tasks. There is a suggestion that this difference may be based on the visual appearance of the word. 1.2.2.2 Consistency Effects Glushko (1979) demonstrated that consistency effects are also found for non-words. A non-word such as ‘hean’ will be pronounced to rhyme with its neighbours all of which are regular (dean, lean, mean). A non-word like ‘heaf’ that has inconsistent neighbours (leaf, deaf) will be named more slowly and is sometimes even given the irregular pronunciation. This demonstrates that there are lexical effects on the reading of non-words. 1.2.2.3 Conclusion The simple suggestion that non-words are read by the GPC route is not accurate. Robust findings indicate that knowledge of real words in the lexicon affects the processing of non-words. (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 1.3 3 Evidence from the Acquired Dyslexias Acquired dyslexias occur after a person suffers some kind of trauma to the (left hemisphere of the ) brain. Previously normal reading processes are disrupted. A tenet of cognitive neuropsychology is that double dissociations revel things about normal processing. In this case a double dissociation is predicted by the dual route model. Some patients should have an impaired direct access and unimpaired GPC route while other patients should show the opposite pattern. 1.3.1 Surface dyslexia Patients make over regularisation errors for irregular words Can read both words and non-words well if they are regular Show no effect of word frequency, part of speech or imagaebility This suggests that there may be an impairment of the lexical route whilst the GPC route remains intact. However, it is very difficult to find clear-cut examples of patients who fit this pattern exactly. It is often the case that there is slight impairment for regular words and some ability to read irregular words. This has led to the suggestion that there may be more than one type of surface dyslexia. The purest cases are termed Type 1 patients. Type 2 patients on the other hand may also have a slight impairment when reading regular words that is interpreted as an additional minor impairment to the GPC route. 1.3.2 Phonological dyslexia Patients are very poor at reading non-words Real words are read well regardless of regularity This suggests that the GPC route may be impaired whilst the lexical route is undamaged Initial Conclusion It seems that these two types of dyslexia do indeed demonstrate a double dissociation, which supports the dual route model. However there are other forms of acquired dyslexia that suggest the situation is more complicated. 1.3.3 Deep Dyslexia As with phonological dyslexics non-words are read poorly In addition there are semantic reading errors for real words such as “hate” for <kill> Therefore it seems that these patients have (in addition to problems with the GPC route) an impairment to a system which normally allows reading though the semantic system. There is considerable debate about deep dyslexia. It is not clear if it is really a syndrome (a set of impairments that always cluster together because they have a single underlying cause) but the balance of evidence suggests it probably is. Also, there is some suggestion that that deep dyslexia may be the result of reading using the right-hemisphere. In this case deep dyslexia would not be relevant to a model of normal reading. However, if we assume that deep dyslexia is a syndrome caused by a lesion in the left hemisphere then we must conclude that it is possible to read through the semantic system in a way that the simple dual-route model cannot account for. 1.3.4 Non-semantic reading Patients can pronounce both irregular and nonwords However, they have no comprehension of the (real) words they read This suggests that in these patients a direct orthographic to semantic route is impaired (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 4 Printed word GRAPHEMES LEXICON NONSEMANTIC READING GRAPHEME – PHONEME RECODING SEMANTIC SYSTEM PHONOLOGY pronunciation Simplified three route model 1.4 Alternatives to the dual route model 1.4.1 Three Route Models In these models the lexical route is split into two. The three routes are as follows. GPC route Route through the lexicon AND the semantic system (for accessing the meanings of imeagable words) Route direct from the lexicon to the phonology (no semantics) 1.4.1.1 Normal Readers Lexical effects on non-words and regularity effects on real words are seen as interaction between the three routes. 1.4.1.2 Dyslexic readers These models claim to account for the 4 types of dyslexia in the following way: Surface dyslexia is seen as a problem accessing the lexicon Phonological dyslexia is seen as loss of the GPC route Deep Dyslexia results from only being able to read through the lexical-semantic route which works imperfectly due to damage or lack of interference from other routes Non-semantic dyslexia is a loss of the route from the lexicon to semantics (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 5 1.4.2 Analogy theories These are single route theories (they have no sub lexical route). Lexicons now access PARTS of written words (e.g. onset and rime). Any competing phonologies for these parts are accessed and the system chooses the most common one. This theory has some difficulty in accounting for the dyslexia evidence and also sometimes makes incorrect predictions for the pronunciation of non-words. 1.4.3 Connectionist Models These models are also single route models. There is no storage of individual words. The models contain 3 levels of units with each unit being connected to every other unit in the level above. The connections between these weights are set by the model itself, which learns from experience. These models often perform badly at predicting the pronunciation of non-words. Initial criticisms suggested that they also could not explain the dyslexia evidence although more recent work has cast doubt on this criticism. Phonological Units Hidden Layer Visual Units Connectionist Model of Reading 1 Simplified connectionist model 2 Reading Development In this section we will consider how children learn to read. Again we are dealing solely with producing sound upon seeing text. 2.1 The Developmental Shift Hypothesis Normally developing children go through a stage of using Grapheme Phoneme Conversion (GPC). As we’ve seen adults use the direct lexical route for words that they know. This has led to the hypothesis that there is a developmental shift from using the GPC route to using the lexical route. However, the evidence does not support this hypothesis. For example an experiment by Barron and Baron (1977) indicated that concurrent articulation does not affect the retrieval of meaning from the printed word even for very early readers. This suggests that they are not using Grapheme-Phoneme Conversion. There is evidence to suggest that the developmental shift may work in the other direction with early readers using the direct route and more mature readers using grapheme phoneme correspondences. One such study is by Condry, McMahon-Rideout and Levy (1979). In part of their experiment they presented subjects of different ages with a target word and two choice words. The subjects had to decide which choice word was semantically more similar to the target word. Sometimes the distracter rhymed with the target and sometimes not. The results showed that as they aged subjects were more influenced by rhyming distracters. Conclusion: If there is a developmental shift between strategies it seems to be that the youngest readers use the lexical route whilst older readers use the GPC route. (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 2.2 6 Theories of Reading Development The two most widely referred to theories of reading development reflect this shift from the lexical to the GPC strategy. 2.2.1 Marsh et al (1981) Stage 1: Linguistic Guessing Children are able to read words if they are always presented in the same way. For example the first words that a child can read are often names of shops or brand names. The child cannot guess at words out of context but if given a context the child’s guess will be based on syntactic and semantic information rather than any visual information from the target. Stage 2: Discrimination net guessing The child now uses graphemic cues to recognise words but only to the extent that is necessary to differentiate all the words in the sight vocabulary. Reading errors are now semantically, syntactically and graphemically based. Stage 3: Sequential Decoding The child begins to use grapheme phoneme correspondences. The child decodes words grapheme by grapheme from the left to the right. The child can still only cope with one-to-one correspondences and reading errors reflect this. Stage 4: Hierarchical Decoding Decoding is no longer grapheme by grapheme. Children can use analogies and conditional rules (such as ‘magic e’). 2.2.2 Frith (1985) Frith decided to modify Marsh’s model in order to make more apparent the links with models of skilled reading. In Frith’s model new strategies are used in addition to older strategies rather than replacing them Stage 1:Logographic The child recognises words using salient graphic cues. The child cannot read novel or non-words. Stage 2: Alphabetic The child uses individual grapheme to phoneme correspondences. Later the child can use conditional rules Stage 3: Orthographic The child recognises strings of letters and accesses pronunciations without decoding these strings. This is very much like analogy theory except the strings that the child uses are whole morphemes rather than onsets and rimes. Conclusion: Both of these models recognise that the lexical direct access route is used before the GPC route. 2.2.3 What causes the shift from the lexical to the GPC strategy? Marsh: Shift from ‘Discrimination Net Guessing’ to ‘Sequential Decoding’ The number of words in the sight vocabulary causes the shift. The child now knows too many words to distinguish them all by different graphemic cues. Frith: Shift from ‘Logographic’ to ‘Alphabetic’ strategies. The shift is caused by the child’s increased phoneme awareness. (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 2.3 Phonological awareness The ability to reflect upon and manipulate the sounds of words 2.3.1 Levels of awareness σ ‘dog’ O R O N d -- og C /d/ /o/ /g/ 2.3.2 Testing phonological awareness ‘pat’, ‘cat’, ‘fan’ Oddity: Odd one out - Phonemic Fluency: Words beginning with /t/ Identification: What’s the sound at the end of ‘rabbit’ Counting: Syllables Phonemes How many syllables in ‘television’ How many sounds in ‘dog’ Segmentation: Syllables Phonemes ‘car’ ‘pen’ ‘ter’ ‘d’ ‘o’ ‘g’ Addition: Syllables Phonemes add ‘pet’ to ‘car’ add ‘p’ to ‘ram’ Deletion: Syllables Phonemes say ‘rabbit’ without the ‘bit’ say ‘rabbit’ without the /t/ Spoonerisms: John Wayne >>> Won Jane 7 (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 2.4 8 Phonological awareness in relation to reading 2.4.1 The Evidence from Children 2.4.1.1 Deletion Beginning readers cannot delete phonemes from words. By the age of 9 children can do the task quite easily (Bruce 1964). Other experiments (e.g. Calfee 1977) have shown that children of all ages perform better when the phoneme to be deleted is the whole onset (e.g. they can delete /s/ from ‘sail’ but not from ‘snail’). 2.4.1.2 Counting Work from the Haskins group in the 1970s suggests that young children can count syllables but not phonemes. 2.4.1.3 Oddity Tasks Pre readers can perform the oddity tasks for initial sounds (onsets) but not for end sounds (codas). Beginning readers perform slightly better for end sounds. Conclusion: Children are aware of syllables and onsets but not codas before they can read. Awareness of codas increases after some reading experience. The suggestion is that they are aware of onsets and rimes but not phonemes when they form only part of these units. 2.4.2 The Evidence from Illiterate Societies Morais et al (1986) compared Portuguese people who either were or had been illiterate as adults. The current illiterates performed worse on all the tasks than the former illiterates but were at a much worse disadvantage for phonemes than for syllables. 2.4.3 The Evidence from readers of Non-alphabetic scripts Read et al (1986) looked at the differences between two groups of Chinese readers. One group had only been taught the traditional Chinese logographic script. The other group had also been taught pinyin, which is an alphabetic script. The logographic group was much worse than the pinyin group on phoneme addition and deletion tasks. 2.4.4 Overall Conclusion People who have not (yet) learned to read have quite good awareness for syllables and onsets and rimes. When a person learns to read their awareness of phonemes increases. However, the script must be alphabetic for this to happen – a logographic script will not increase phoneme awareness. Syllable Awareness Dog Onset-Rime Awareness d - og Phoneme Awareness /d/ /o/ /g/ Developmental Progression Alphabetic Reading (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight 2.5 9 The Child’s use of Analogy 2.5.1 At what stage do children use analogies? The models of both Frith and Marsh suggest that analogy type reading occurs at the last stage of development. However the fact that children are aware of onsets and rimes from an early stage (and are very sensitive to rhyme and alliteration) might suggest that they use this awareness to help them read by analogy. 2.5.2 Evidence for the early use of analogies Goswami found that even beginning readers can read new words by using analogies with words they already know. The new words in the study could not have been read by grapheme-phoneme conversion because they were irregular (e.g. beak). Neither could they have been read by the direct lexical route as a pre-test determined which tests words were known by each child 2.5.3 Goswami and Bryant’s Theory of Development This is a slightly different theory of reading as it does not have distinct stages but rather it has causal links in a chain. These are as follows: Before they learn to read children are aware of onsets and rimes (this awareness is facilitated by games which focus on rhyme and alliteration). When they learn to read they use this awareness and recognise that words with the same rimes are written with the same letters. This allows them to make analogies in order to read new words. As they have more exposure to the alphabetic script children become aware of phonemes. Later on they use this awareness to use GPC strategies in reading. (Introduction to) Language History and Use – Psycholinguistics Reading Rachael-Anne Knight Glossary Grapheme: A letter or combination of letters that represents a phoneme Concurrent Articulation: In certain experiments subjects are asked to constantly repeat a string of sounds (e.g. ice cream) while performing another task References Review Chapters Coltheart (ed.) (1987) Attention an Performance XII: The Psychology of Reading, Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum (especially chapter 19 for adult reading) Ellis, A. (1993) Reading, writing and dyslexia: A cognitive analysis, Hove, Lawrence Erlbaum Eysenk, M. and Keane, M. (1995) Cognitive Psychology, Hove: Psychology Press (Chapter 12 for adult reading, chapter 1 also has some information on neural nets) Harley, T. (1995) The Psychology of Language, Hove: Psychology Press (Chapter 4 for both topics) Harris, M. and Coltheart, M. (1989) language processing in Children and Adults, London: Routledge (chapter 4 for learning to read and chapter 9 for dyslexia both available on reserve in the MML library) Perfetti, C. (1994) “Psycholinguistics and Reading Ability” IN Gernsbacher, M. (ed.) Handbook of Psycholinguistics, San Diego: Academic Press (for learning to read and phonological awareness) Rayner, K. and Pollatek, A. (1989) The Psychology of Reading, Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum (Chapter 13 for models, chapter 11 for dyslexia and 10 for development of reading) Wolf, M., Vellutino, F. and Gleason, J. (1998) “A Psycholinguistic Account of Reading” IN Gleason, J. and Ratner, N (eds.) Psycholinguistics, Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace (for both subjects but especially a very thorough review of models) Some Original Papers Models Glushko, R. (1979) “The organization and activation of orthographic knowledge in reading allowed”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 5, 674-691 Coltheart, M., and Rastle, K. (1994) “Serial processing in reading aloud: Evidence for dual-route models of reading”, Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20, 1197-1211. Hinton, G., Plaut, D. and Shallice, T. (1993) “Simulating Brain damage”, Scientific American, 269 vol4, 58-65 Learning to Read Goswami, U. and Bryant, P. (1990) Phonological skills and learning to read, London: Lawrence Erlbaum 10