Heritage of the Upper North Region: Background History-2

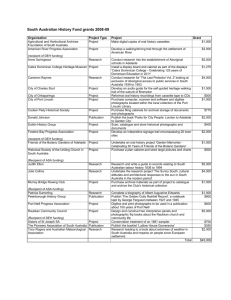

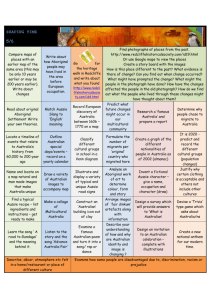

advertisement