43 Battery (Lloyd`s Company) The Battle of Waterloo Introduction On

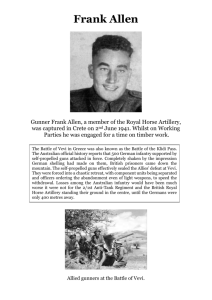

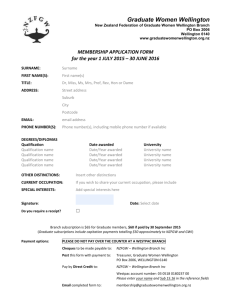

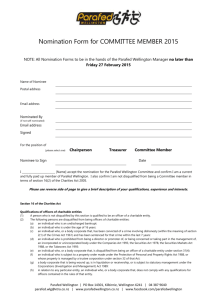

advertisement

43 Battery (Lloyd’s Company) The Battle of Waterloo Introduction On the 1st of February 1808, 10th Battalion Royal Artillery was raised. 2nd Company was commanded by Captain William J Lloyd (from whom the Battery takes its name). Armed with the then state-of-the-art 9 Pounder field gun their first action was to move to Walcheren in The Netherlands, but on arrival at the Dutch coast the British forces were evacuating so the Battery returned to Woolwich with the remainder of the British Army which had suffered heavy losses in a failed attempt to destroy Napoleon’s fleet at Antwerp.1 Between April 1811 and April 1815 the Company moved between Woolwich, Exeter and Plymouth, before embarking to Canada to fight in the War of Independence. However, they were diverted to Flanders, via Cork, as Napoleon’s escape from exile meant another British Army was needed in an Alliance with Russia. As a result, the Company landed at Ostend on 11 Apr 1815. Within weeks they were issued guns and equipment (5 x 9 pounders and 1x 5.5 inch howitzer) and became Major WJ Lloyd’s Brigade of Guns and allocated to the 3rd Division of the British 1st Corps in the Army of the Low Countries under the Command of the Duke of Wellington, also known as The Iron Duke. Fig. 1. 9 Pounder (1) 1 Duncan, Capt, F. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, J. Murray, 1873. p.451 WATERLOO CAMPAIGN The summer of 1815 saw the three Armies of Bonaparte, Wellington and Blucher manoeuvring across the plains of modern day Belgium (at the time it was part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands). Napoleon, with about 100,000 men was heavily outnumbered by the Allies (68,000 with Wellington and 89,000 with Blucher). The town of Quatre-Bras was of great strategic importance because the side which controlled it could move south-eastward towards the French and Prussian Armies at the Battle of Ligny. If Wellington could link up with General Blucher’s Army the force would greatly outnumber Napoleon’s. Napoleon planned to move into modern day Belgium and split the coalition Armies, then destroy the Prussian Army before turning his attention to Wellington’s force. Although the Allies had some intelligence of French plans, Wellington was heard to remark, “Napoleon has humbugged me, by God; he has gained twenty-four hours' march on me.” Wellington first heard of the outbreak of hostilities on the 15th of June 1815 from the Prince of Orange and after further reports of additional fighting Wellington ordered his Army to concentrate and move toward the Prussians. After a build-up and manoeuvring of Allied troops within Quatre-Bras and French troops surrounding the village there were a number of intense skirmishes beginning on the afternoon of the 15th of June and carrying on to the afternoon of the 16th when the real fighting began. The Battle of Quatre-Bras Fig. 2. The positions at the Battle of Quatre-Bras. (2) The French had amassed 22 guns and began bombarding Allied positions, at the time occupied mostly by Dutch soldiers under the command of William, Prince of Orange. The bombardment was followed by an intense battle of French columns supported by skirmishers forcing the Allies to pull back. In the face of two French Infantry Divisions and a Cavalry Brigade, the Allied 2nd Division’s position was perilous. At 3pm, The Iron Duke arrived with a British Infantry Division and a Dutch Cavalry Brigade. He immediately took charge and directed forces to halt the French advance to the east. Fighting broke out all along the line and Dutch forces had to withdraw into Bossu Wood where they fought the French from tree-to-tree. The intense fighting continued through the afternoon with forces capturing, withdrawing and recapturing key positions. This included the tactically significant Germincourt Farm which the Dutch held, lost, held again, but then finally had to withdraw. Napoleon’s brother, Jerome, also finally managed to drive most of the allies from Bossu Wood. His troops forced the, mainly British, soldiers almost all the way to the crossroads. The Allies however, held out until at 5pm when General Alten’s, 3rd Division arrived only shortly preceded by Lloyd’s Guns. The French 1st Corps had, without the knowledge of the Field Commander, General Ney, moved to reinforce the main French-Prussian Battle at Ligny. General Ney was then ordered to seize Quatre-Bras once and for all and move to support the Battle at Ligny. He could not do this without the support of the 1st Corps and ordered their return immediately. At this stage the French controlled the majority of Bossu Wood and Ney thought he could now cut-off Wellington. He ordered a Brigade of Cavalry men armed with sabres and pistols to keep the pressure on Wellington’s forces. The French Cavalry charge was vicious and caused the 63rd Brigade, to lose their King’s Colour, the ensign hacked down by 23 sabre cuts. This was the only King’s Colour under Wellington’s direct command that was ever lost. The remaining two Infantry Brigades managed to rally in the Allied portion of Bossu Woods and effectively regrouped. Fig. 3. French Cavalry (Cuirassiers) attack the 42nd Highlanders at Quatre Bras (3) Captain William Lloyd was ordered to deploy his guns to support the Duke of Brunswick’s troops from French Artillery fire. They had to deploy so close to the French Batteries that before they could even be unlimbered horses had been killed and wheels shredded from their axels. Men were literally cut in two from being hit with shells from the French side. Nevertheless the Battery managed to silence the French Guns, and forced the withdrawal of a French Column of Infantry that was to trying to turn the British forces. Lloyd lost the equivalent of two full gun teams and had to abandon two guns during the action, but they were later recovered and reconstituted for the next day.2 The arrival of the 1st Guards Division following this allowed Wellington to recapture Bossu Wood and when the British forces attempted to leave the wood they were met with intense French Artillery fire and forced back. 2 Lipscombe, N. Wellington’s Guns, Osprey Publishing, 2013. p.362 By 9pm the French had been forced to give up all their territorial gains in the area, a tactical victory on a strategic objective. The Allies lost around 4500 troops and the French 4000 troops at the Battle of Quatre- Bras with neither side suffering decisive losses. Napoleon had however, triumphed at Ligny and beaten the Prussian Army who had to withdraw North West. Wellington was forced to abandon his position and moved toward them. Napoleon chose to follow and met two days later at Waterloo. The Battle of Waterloo Napoleon decided to seek battle and defeat Wellington before the British and Prussian Armies could join up. He dispatched a small force under Grouchy to delay Blucher and marched his Army towards Quatre Bras. Wellington had positioned his force on a small ridge at Mont St John, near to the small town of Waterloo. He made use of four strongpoints around which he deployed his forces. The strongpoints were the Hougoumont farm, the farmhouse La Haye Sainte and the houses of La Haie and Papelotte. Wellington believed that he could hold Napoleon in the position, but only until Blucher arrived. Lloyd’s Company was deployed in the front line, near Hougoumont farm, which was defended by the Brigade of Guards. Fig. 4. Battle picture at Waterloo (4) The Battle began at 11am with an Artillery salvo by the French, followed by an attack on Hougoumont farm. The attack on the farm lasted all day, involving up to 10,000 French troops. At about 4pm, after five hours hard fighting, Wellington reorganised his forces. General Ney may have mistaken this for a retreat, as he then ordered a Cavalry charge of 4,000 horses. Lloyd’s Company’s position was very exposed and under constant French fire, but the guns continued to fire as the Cavalry charged. The Battery kept firing until they were overwhelmed. The Gunners then removed a wheel from each gun carriage, temporarily disabling the guns. They ran for shelter in the Infantry squares, bowling the wheels along with them. When I reached Lloyd's abandoned guns, I stood near them for about a minute to contemplate the scene: it was grand beyond description. Hougoumont and its wood sent up a broad flame through the dark masses of smoke that overhung the field; beneath this cloud the French were indistinctly visible. Here a waving mass of long red feathers could be seen; there, gleams as from a sheet of steel showed that the cuirassiers were moving; 400 cannon were belching forth fire and death on every side; the roaring and shouting were indistinguishably commixed — together they gave me an idea of a labouring volcano. Bodies of infantry and cavalry were pouring down on us, and it was time to leave contemplation, so I moved towards our columns, which were standing up in square. - Major Macready, Light Division, 30th British Regiment, Halkett's Brigade The French Cavalry crested the ridge at the canter. Only then did they see the square Infantry formations on the reverse slope. Volleys of controlled musket fire decimated the cavalry as they rode past the red squares. The French Cavalry repeatedly reformed and recharged. Six times the Gunners took shelter in the squares only to return to the guns and fire at the fleeing French Cavalry as they reorganised for another charge. If Ney had used Infantry as well as horsemen, then the British may well have been beaten, but Cavalry alone could do little. During this period of the Battle, whilst giving orders to Lieutenants Wells and Phelps, Captain Lloyd was mortally wounded by a French Cuirassier.3 Fig. 5. Lloyd’s Company at Waterloo. (5) Deadlock continued until past 7pm. Napoleon had only one remaining chance for victory before the Prussians could join the Battle. With Blucher’s main body still on the march and Wellington’s centre weakened by a day of fighting, Napoleon committed his final reserve to Battle. Seven Battalions of the Imperial Guard marched up the slope between Hougoumont Farm and the Ohain crossroads. Napoleon’s intention was to slice through the centre of the Allied line, which he believed to be close to breaking point. 3 Lipscombe, N. Wellington’s Guns, Osprey Publishing, 2013. p.382 Lloyd’s Company, with the rest of the British Artillery, poured fire into the French columns. This caused the Guard to falter, but each time a man fell the French closed ranks and continued to march on. On reaching the top of the slope, the French were met by volley upon volley of musket fire. The columns of the Imperial Guard reeled back and the British Infantry charged. The French turned and were forced to reform a distance down the hill. The French approached a second time, their lines broke whilst being out-flanked, and they were subjected to horrific crossfire. The French advance disintegrated as the Old Guard, for the first time, broke and fled. Seeing this, the rest of Napoleon’s Army collapsed and also fled. Fig. 6. The Battle of Waterloo (6) Defeating Napoleon had been costly for the Allies. Wellington lost 15,000 men, Blucher 7000, and Bonaparte 32,000, with at least another 7000 captured. Lloyd was taken to Brussels, where ten days later he died of his wounds, he is buried at St Josse Ten Noode Cemetery, on the south side of the Chaussée de Louvain.4 Losses throughout his Company of Artillery were severe: one Officer and 10 men killed, one Officer and 24 men wounded with one man missing out of a total of 98 soldiers. The Commander Royal Artillery, Sir George Wood, wrote of Captain Lloyd, that, “A braver or more zealous man has never entered the field of battle”.5 After the Battle of Waterloo, Lloyd’s Company remained in France with the Army of occupation, until March 1816 before returning to Woolwich, via Paris. The economic axe fell on the youngest Battery in the 10th Battalion and the Company was disbanded on the 31st of March 1817.6 Picture Credits 1. Ree, K. 9-pounder Gun. 2006 2. Fremont-Barnes, G. Battle of Quatre Bras Map. 2006 3. Wollen, W.B. Quatre Bras (Black Watch at Bay) 4. Ipankonin. Waterloo Campaign Map. 2007 5. Rowlands, D. Captain Lloyd's Company RA at Waterloo.Year unknown 6. Dighton. D. The Battle of Waterloo. c.1816 4 http://www.gutenberg.org/, Lady De Lancey. A Week at Waterloo in 1815, J. Murray, 1906 5 Duncan, Capt, F. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, J. Murray, 1873. p.437 6 Hime, Lt. Col. H.W.L. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery 1815-1853. Longmans, Greene and Co., 1908. p. 121