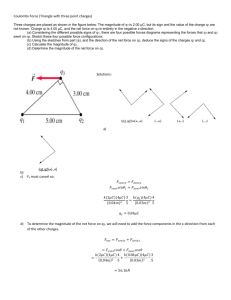

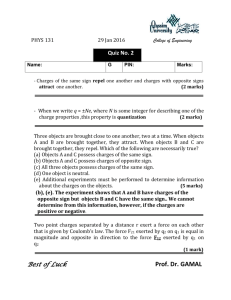

here

advertisement