ATSDR Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual

advertisement

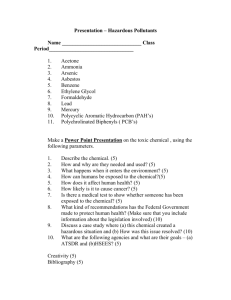

1/30 FACTS ON THE NORTH CAROLINA ATSDR HEALTH STUDY ATSDR Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual – Assessment of Requirements and Actions Steven P. Levine, Ph.D., CIH; Emeritus Professor, University of Michigan June 6, 2004 Contents I. Executive Summary II. Introduction III. Discussion IV. Comments and Lessons Learned Recommendations Appendix A. Peer-reviewed publication analyzing the ATSDR Trinity-Glenola study I. Executive Summary In August 2003 the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) issued a contract to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) to initiate the first stages of a project to measure and evaluate the correlation of possible emissions from flexible polyurethane foam (FPF) plants to health effects in individuals living in communities nearby to the FPF plants. This correlation was expected to prove a causal link between the presence and operation of the FPF plants, the emissions of TDI from those plants, and asthma in the nearby communities. To prove correlation and causation, quantifiable and reliable data must be gathered to demonstrate that an exposure pathway actually exists. This kind of study is governed for ATSDR by the “ATSDR Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual”. Prior to the start of any monitoring activity, the design of this study was fatally flawed because it failed to include the requirements of the ATSDR Manual, Chapter 3. “Evaluating Site Information” to investigate other sources of exposure and adverse health effects. The ATSDR Manual, Chapter 6 “Identifying and Evaluating Exposure Pathways” requires the following, which was not performed: “The health assessor should identify the data gaps that exist in each of the… elements [of exposure assessment], and explain how they affect ATSDR's assessment of a specific pathway. In particular, the health assessor should identify contaminants for which insufficient Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 2/30 information exists on transport mechanisms and/or route of exposure and indicate that that data gap prevents complete assessment of the identified contaminant until the data are available.” The investigators had no information on plant operations or operating times, or on the meteorological conditions, nor of any of the known or suspected cross-contaminants. This renders ATSDR’s exposure assessment data invalid. The ATSDR Manual, Appendix C. “Data Evaluation Criteria” gives the requirements for collection, analysis and acceptance of data gathered in such a study. This appendix is centrally important to the analysis presented in this report. The practices of the ATSDR-NCDHHS team are in complete nonconformance with virtually every requirement of this appendix. This was the same case in the ATSDR study at Glenola, NC. No consideration has been given to the quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) requirements prescribed in the Manual. None of the data that has been gathered to date should be used. The ATSDR Manual, Chapter 8. “Determining Conclusions and Recommendations” requires: “The final task in preparing a health assessment is to determine conclusions about the health implications associated with the site and to prepare parallel recommendations…. In selecting the appropriate health hazard category, the assessor must consider the total body of information available for the site.” Exposure pathways have not been completed, on-site and off-site contaminant concentrations have not been determined, and the gaps in the environmental characterization data are so egregious that the project should be stopped. The ATSDR Manual, Chapter 9. “Health Assessment Format” requires that “The Summary should be a concise synopsis of the health assessment.” The flaws are so egregious that this project should be stopped until an impartial peer-review panel evaluates the need for, design and funding level of the study, and oversees its implementation and analysis of the data. Recommendations for further actions are given in Section IV of this report. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 3/30 II. Introduction In August 2003 the ATSDR issued a contract to the NCDHHS to initiate the first stages of a project to measure and evaluate the correlation of possible emissions of TDI from FPF plants to health effects in individuals living in communities nearby to the FPF plants. This correlation was expected to prove a causal link between the presence and operation of the FPF plants, the emissions of TDI from those plants, and asthma in the nearby communities. To prove correlation and causation, quantifiable and reliable data must be gathered to demonstrate that an exposure pathway actually exists. This kind of study is governed for ATSDR by the “ATSDR Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual” http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/HAGM/ last updated June 25, 2001. This manual is hereafter referred to as the “Manual”. In this report, a comparison will be made between the Manual and the activities of ATSDR and NCDHHS. III. Discussion The comparison will follow the structure of the Manual. Chapters 3 and 6, Appendix C, Chapters 8 and 9, of the Manual will be used for this comparison. Appendix C is discussed before chapters 8 and 9 because chapters 8 and 9 primarily related to conclusions, whereas Appendix C relates to methods and data. In the Note to Users of this Manual, it states: “[This] is a guidance document for health assessors both at ATSDR and the states. It outlines the health assessment process and provides information to the health assessors on different technical and scientific aspects of performing public health assessments.” This means that all such studies performed by ATSDR will conform to the requirements of the Manual. To further confirm this, Manual Chapter 1 – Introduction, states: “This document sets forth the health assessment process as defined by ATSDR, clarifying the methodologies and guidelines that will be used by ATSDR staff and agents of ATSDR in conducting these health assessments… This document is directed at ATSDR public health physicians, scientists and engineers, and other state and federal agencies that perform health assessments.” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 4/30 Some of the language of the text of the Manual is clearly intended for application to remedial action sites, such as Superfund sites. However, the Manual itself makes it abundantly clear that the Manual applies to all ATSDR activities. In this report, references will be made to both documented activities of the ATSDR-NCDHHS team, and to the document “Environmental Exposure to Diisocyanates and Respiratory Effects”. Protocol – Pre-Decisional Draft (March 17, 2004). How a project could be underway based on a protocol that is marked “Pre-Decisional Draft” is entirely unclear, as is the use of the language and the designation “Pre-Decisional Draft”. Furthermore, this Pre-Decisional Draft refers to and is based on the justification of work performed at Glenola, NC, at the Trinity American Company site. References given leave out the peer-reviewed critique of this study, which objectively demonstrated that the ATSDR-NCDHHS Glenola study was illplanned, poorly implemented, incompletely documented, led to unsupportable conclusions, and violated virtually every tenet of the ATSDR’s own Manual. (Appendix A). Environmental and occupational health interventions are central to the protection of human health and well-being. It is essential that interventions be based on sound science and methods, and by reducing exposures thereby reduce the risk of adverse health effects. Risk determinations must be based on sound science and methods. That is the basis for this critique of the ATSDR project. (Bolded text represents emphasis added to quoted text.) 1. Manual – Chapter 3 “Evaluating Site Information” “3. No analysis of the threat posed by site contamination can begin without the health assessor first becoming familiar with the site, its setting, and its history… To begin a health assessment, the assessor needs to have site-specific knowledge about the following categories: 1. Background (site description, operations, history, regulatory involvement); 2. Community health concerns; 3. Demographics (characterization of populations at and near the site that may potentially be exposed to hazardous materials); 4. Land use and natural resource use information (land use and natural resources at and adjacent to the site); 5. Environmental contamination (chemicals and concentrations identified in specific media); Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 5/30 6. Environmental pathways (contaminant fate and transport mechanisms within the respective media); and 7. Health outcome data.” … in general, the greater the site-specific knowledge the assessor has about those seven categories of information, the greater the accuracy of health assessment conclusions.” “3.1.1. Location of the site within the community provides insight about both the size of the population potentially affected by the site and other sources of contamination.” “3.4 A review of land use at or near the site is necessary because it provides valuable information on the types and frequency of activities of the surrounding population and the probability for human exposure… Industrial areas near the site that may potentially contribute to the exposure- related body burden of workers and residents should be noted… Residential areas and indicators of lifestyle factors that may influence exposures or health implications should be identified (low-income or poverty-level housing, scavenged drums and materials, gardens, livestock, and private wells).” Comments: There is ample objective evidence that key aspects of these steps were not carried out. In particular, the areas surrounding the FPF plants were not surveyed for other sources of isocyanate emissions, especially those emissions that might interfere with measurements meant to assess the dispersion of diisocyanates from the FPF plants. These surveys must include complete current and historical evaluation of the chemical emissions of all the facilities within the “zone of influence”, and must be conducted on each piece of property in the study area using, at a minimum, ASTM method E50 Environmental Assessment (the standard for environmental assessment of property). On December 3, 2003, representatives of Future Foam of North Carolina met with ATSDR representatives who delivered information about this project. When asked why Vitafoam and Future Foam plants, which are within a few miles of each other, were both being monitored, ATSDR responded that it was because of EPA TRI data. Future Foam said that they were only reporting a couple of pounds per year of emissions, which number was artificially high because their carbon adsorbers are essentially 100% efficient. The North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources would not accept that efficiency claim. Future Foam then presented information showing multiple sources of potential diisocyanate use and possible release from other companies in the immediate vicinity of their plant, including two major Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 6/30 chemical operations within 1/4 to 1/2 mi of the plant. In addition, there are no zoning-compliant residences within the down wind area of the plant, which is zoned “industrial”. (A residence within an industrial area is not zoning compliant and usually cannot be rebuilt if it is damaged.) ATSDR did not appear knowledgeable in this area. When asked why they did not investigate other possible emission sources that could interfere with the test, ATSDR said they were only interested in foam facilities. Objective evidence to the effect that there are other sources that could interfere with the test: 1. Aerial photo with the FFNC plant represented by the black rectangle (middle of picture). Dots = identified businesses. Scale is 1 in = 100 M (all figures/tables from L. Knudtson, Future Foam) Table 1. List of factories surrounding Future Foam plant. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 7/30 Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 8/30 2. Aerial photo with the highlighted area 1/4 mi from the sides of the plant (marked by X) 3. Aerial photo with the FFNC plant with the highlighted area = 1/4 mi to 1/2 mi from the plant Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 9/30 4. Zoning map of High Point available from the city's web site Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 10/30 Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 11/30 5. Zoning map - Future Foam location = black rectangle in the middle. This map shows that the only zoned residential area is located up-wind from Future Foam and is surrounded by heavy and light industrial zoning, with many potential sources of diisocyanate emissions. 6. US EPA Enviromap of all sources of emissions in High Point. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 12/30 These figures illustrate other possible sources of contamination and ATSDR did not do the investigations required before starting their monitoring activities required in their own Manual: “3.1.1. Location of the site within the community provides insight about both the size of the population potentially affected by the site and other sources of contamination.” “3.4 A review of land use at or near the site is necessary because it provides valuable information on the types and frequency of activities of the surrounding population and the probability for human exposure… Industrial areas near the site that may potentially contribute to the exposure- related body burden of workers and residents should be noted…” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 13/30 Furthermore, there is no evidence that they investigated lifestyle factors that might be contributory to either asthma or to diisocyanate exposure (such as the hobby of car restoration or repair or home “cottage industry”) required by their manual: “3.4 A review of … Residential areas and indicators of lifestyle factors that may influence exposures or health implications should be identified (low-income or poverty-level housing, scavenged drums and materials, gardens, livestock, and private wells).” It also does not appear that ATSDR investigated the area around Vitafoam. Factories within a one mile radius of the plant are: Business Address Notes Ron’s Auto Repair D&D Asphalt Paving Co. ABC Iron Works “Un-named Metal Bldg.” Piedmont Marble Co. Triangle Ice Inc. Piedmont Paper Stock HBD Inc. Duke Power substation RAD Performance “Un-named Metal Bldg.” 4140 Pleasant Garden 3625 Pleasant Garden Road 5625 Pleasant Garden Mechanical, body work. Vehicle painting. Paving equipment + non-commercial auto repair. Metal fabricators (Basement of D&D Asphalt) 3600 Pleasant Garden 3326 Pleasant Garden 3324 Pleasant Garden 3909 Riverdale Rd. 3901 Riverdale Rd. Non-manufacturing. Storage. Synthetic marble sinks. Resin use. Ammonia. Organic refrigerants. Corrugated paper, non-manufacturing Plastic bags, nets, containers, printed apparel. Riverdale Rd. 3429 Elm-Eugene St. Transformers, potential VOC emissions. Auto wheels, tires, hubcaps. 824 Wiley-Lewis Rd. Diamond Hill Plywood Southeastern Plastics 601 Diamond Hill Rd. 605 Diamond Hill Rd. Non-manufacturing? Storage. Oriented Strand Board, Fiberboard, Distribution. Non-manufacturing. Office only. General neighborhood Pleasant Garden Rd. area. Observations of residents burning trash/garbage Does this list mean that there are diisocyanate emissions from businesses surrounding Vitafoam? Not necessarily. But it does mean that, unless ATSDR has investigated these businesses, they have not fulfilled the requirements of the Manual. In addition the ATSDR Pre-Discussional Draft Protocol requires: “For each target site identified, a comparison site will be identified. Comparison sites will be based on proximity and similarities in age, race, and income distributions, as well as the absence of any industrial point sources for diisocyanates.” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 14/30 There is no information available from ATSDR about the comparison sites. Since many of the parameters required to be identified in the Manual Chapter 3 were not identified for the “exposed” populations, it is not clear how comparison sites can be defined, with all parameters being normalized except exposure. Knowledge of all factors is required in any epidemiological study. Lesson Learned: Prior to the start of any monitoring activity, the design of this study was fatally flawed because it failed to include requirements of the ATSDR Manual, Chapter 3. “Evaluating Site Information” to investigate other sources of exposure and adverse health effects. 2. Manual – Chapter 6 “Identifying and Evaluating Exposure Pathways” “An exposure pathway is the process by which an individual is exposed to contaminants that originate from some source of contamination… An exposure pathway consists of… five elements [two of which are listed here]: 1. Source of contamination (source of contaminant release into the environment, or the environmental media responsible for causing contamination at a point of exposure if the original source of contamination is unknown); 2. Environmental media and transport mechanisms (environmental media include waste materials, groundwater, surface water, air, surface soil, subsurface soil, sediment, and biota. Transport mechanisms serve to move contaminants from the source to points where human exposure can occur)…” “The health assessor should identify the data gaps that exist in each of the five elements, and explain how they affect ATSDR’s assessment of a specific pathway. In particular, the health assessor should identify contaminants for which insufficient information exists on transport mechanisms and/or route of exposure and indicate that that data gap prevents complete assessment of the identified contaminant until the data are available.” “6.1. Identifying Element 1 – Source of Contamination: …Sources of contamination are not always obvious. The health assessor needs to consider a number of factors before deciding whether contamination existed, exists, or could exist in the future. Some of those factors include the following: location or release point; Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 15/30 history of storage, disposal, or release; contaminants and concentrations at the source; emission rates ; frequency of release; operating period; and current status.” “The emission rate and frequency of release from the source will help determine the importance of evaluating this source further. The operating period is crucial in determining the importance of the release point over specific time periods, particularly if the releases involve some human element of control. Knowing the operating period and the current status will assist in determining the relevant time period that should be considered when assessing the exposure pathway.” Comments: The history and current uses of sites must be investigated. Web-based or governmental databases do not always have such information in complete or accurate form. Historical changes in operations at sites proximal to residential areas could have significant effects on past or present adverse health effects in the community. “6.2. Identifying Element 2 – Environmental Media and Transport: …During the analyses of contaminant fate and transport in an environmental medium, the health assessor should try to answer the following questions: At what rate are contaminants entering the medium? (emission rates) Where are the contaminants going and how fast are they migrating? (advection) How are the contaminants spreading out in the medium? (dispersion) What is the degree of buffering or degradation of contaminants as they migrate? (attenuation) Will contaminants migrate to another medium? (inter-media transfers) What about past and future exposures?” “6.2.3. Site-Specific Factors Influencing Environmental Fate and Transport. When identifying possible transport pathways, the assessor should also consider site-specific factors that may affect contaminant transport… Wind speed and direction influence generation rates of fugitive dust [and transport of vapors].” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 16/30 Comments: One site-specific factor for diisocyanates is that such compounds react readily with moisture. Therefore, for TDI in situations in which there is even a relatively short residence time in a stack prior to emission to the environment, a significant fraction of the TDI might be eliminated. This, then, would affect the results of stack sampling and emission modeling for TDI on stacks in plants that have carbon adsorbers and similarly on plants that do not have carbon adsorbers. “6.2.4. Representativeness and adequacy of the environmental sampling conducted at the site. “This section provides guidance for determining whether environmental data are sufficient to characterize contaminant transport and the extent of contamination. Section 5.3.3. provides additional information on this topic for each of the media. The health assessor should conduct the following steps [including] 1. Review the deficiencies in the number, location, time coverage, and quality of the samples.” “AIR When assessing air data, state how useful the data are based upon sampling duration. Indicate if the sampling duration is representative of acute (less than 14 days), intermediate (15-364 days), or chronic (greater than 365 days) exposure. Indicate whether or not the air sampling was conducted at the breathing zone. Verify, using on-site wind rose information, that the air monitoring station(s) is (are) located downwind from the site. If on-site meteorologic data do not exist, state the distance to the closest meteorologic station with wind rose data and discuss how representative it is of the site…” “6.2.5. Environmental Transport Models: Environmental modeling is used for both qualitative and quantitative analysis of contaminant transport at a site. There are some instances when the assessor may use environmental transport models to assist in conceptualizing the transport mechanisms and the factors affecting them at a site. Some specific uses of environmental modeling include the following: to evaluate and recommend sampling locations; to identify data and information gaps; to describe temporal and spatial trends for contaminant concentrations at an exposure point; to estimate the duration (e.g., years) of exposure; and Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 17/30 to estimate contaminant concentrations at exposure points in the past or in the future when monitoring data are not available. The assessor should recognize that models contain assumptions that influence the validity of the predictions derived from the model. Therefore, before relying on data derived from modeling, the assessor should ensure, whenever possible, that the model being used has been validated and calibrated using site-specific data.” “The validity of those assumptions is often difficult to establish on a site-specific basis. For that reason, ATSDR believes that such models or mathematic expressions are tools that should be used only as guides to help develop public health decisions and should not replace decisions based on comprehensive, validated, environmental samples. The health assessor should not use the predicted environmental concentrations from models to estimate exposure doses in humans, or to draw health conclusions…” “Although ATSDR strongly recommends the use of validated analytical data as the basis for public health conclusions, it may be necessary to rely on modeling data when analytical data are not available. If modeling data are used in the health assessment, the data should be clearly identified as such, and the uncertainty and limitations of the data should be explicitly acknowledged.” “6.5.3. Estimation of Receptor Populations: ‘Health assessors estimate the persons exposed or potentially exposed to contaminants for each exposure pathway…. Health assessors should use the following steps as a guide in estimating the receptor population [including] 1. Before the site visit, evaluate the completed and potential pathways… from the available data. 2. During the site visit, further evaluate the exposure pathways by examining site access, use (work, play, riding, recreation, hunting, fishing), and local points of exposure…” Comments: The Manual, Chapter 6, requires that the investigators have data specifically defining, at the time during which exposure monitoring takes place: Plant operations; Plant operating times; Plant emission rates; Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 18/30 Meteorological conditions; and Other sources of emissions. As far as can be ascertained, the ATSDR collected little, if any, of this information while air monitoring (exposure assessment) was being carried out. For example, at Prestige Fabricators of Asheboro, NC, monitoring was performed without regard to the facts that: a weather station at that site had not been installed; the ATSDR and the NCDHHS did not request meteorological measurements from Prestige’s own weather station; Prestige tried to contact ATSDR-NCDHHS for the two month period of the monitoring with no response from the investigators; The ATSDR never requested plant operating times or conditions from Prestige during this period. At the Vitafoam Greensboro, NC, site the weather station was not operational during some periods when air monitoring was taking place. Meteorological data was used from the airport weather station that was 18.5 miles distant from the study site. In the Pre-Decisional Draft Protocol, ATSDR states: “Based on air monitoring and weather data, refined air modeling will be conducted to define the exposed area in the target communities.” Clearly, this was not done. It was also not performed at Future Foam. The weather station was not retrieved and meteorological data was not read as of May 25, 2004, and by that date Future Foam had already been told the results of the ATSDR study. In the Pre-Decisional Draft Protocol, ATSDR covers their bases by making a complaint about lack of cooperation from the FPF plants before such cooperation is even requested: “Diisocyanate releases may be difficult to capture without an understanding of the timing of releases from the point source. It may be difficult to obtain cooperation from the owners of the point source. However, in the absence of such cooperation from the Trinity American Corporation, ATSDR was still able to capture diisocyanate releases during the exposure investigation described above.” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 19/30 This is not only a complaint before the fact, but it is also incorrect in that the ATSDR did not capture diisocyanate releases during the Trinity exposure investigation. In addition, in the Pre-Decisional Draft Protocol, ATSDR states: “Existing information on particulate matter, ozone, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide will be collected for both target and comparison communities.” Apparently, this has not been performed at the study sites. To do this would have required the colocation of the TDI monitors and monitors for these other substances. Just putting these monitors in “the area” would have been insufficient because of the very high probability of localized concentration gradients (for example, from diesel exhaust) Finally, environmental emission and transport modeling (Manual, section 6.2.5) must be used prior to the initiation of an exposure and health effects study. If modeling shows that there are no TDI emissions to the community that either exceed applicable (and very stringent) regulations or otherwise have the capacity to impact the health of the community, then no study should even be initiated. Such data was ignored in this case, and the study was started despite the fact that dispersion modeling would have demonstrated full compliance with North Carolina air emissions regulations. Thus, every aspect of the ATSDR Manual, Chapter 6, “Identifying and Evaluating Exposure Pathways” was not followed by the investigators. Lessons Learned: The investigators had no information on plant operations or operating times, or on the meteorological conditions, nor of any of the known or suspected cross-contaminants. This renders ATSDR’s exposure assessment data invalid. 3. Manual - Appendix C. “Data Evaluation Criteria” This appendix is centrally important to the analysis presented in this report. The practices of the ATSDR-NCDHHS team are in complete non-conformance with virtually every requirement of this appendix. This was the same case in the ATSDR study at Glenola, NC. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 20/30 “C.1. REVIEW - DATA REQUIREMENTS: Before data can be evaluated, there must be an understanding of necessary information and criteria enabling judgment of data acceptability. The investigator should be familiar with: data quality objectives (the anticipated use for which samples were taken and which consequently determines types of laboratory analysis and data quality), and quality assurance/quality control requirements (type of information required to determine data accuracy and precision of data collected).” “C.1.1. Data Quality Objectives [DQOs]: …Throughout the project planning process, DQOs are supplied through qualitative and quantitative statements in documents such as sampling plans, work plans, and quality assurance plans. Familiarity with a site's DQOs will aid the data reviewer in understanding the quality of data provided and their potential limitations. In general, DQOs define data quality criteria and other analytic considerations, such as: definitions of criteria most commonly used to specify project data requirements and to evaluate available analytical options, namely: o precision (the reproducibility of measurements under a given set of conditions), o accuracy (the bias in a measurement system. Sources of error are the sampling process, field contamination, preservation, handling, sample matrix, sample preparation, and analysis technique.), o representativeness (the degree to which sample data accurately and precisely represent an environmental condition. This criterion is best satisfied by making certain that sampling locations are selected properly and a sufficient number of samples collected…), o completeness (the percentage of measurements made that are judged to be valid measurements. The completeness goal is essentially the same for all data uses: a sufficient amount of valid data must be generated.), o comparability (a qualitative parameter expressing the confidence with which one data set can be compared with another…); guidelines and definitions for minimal quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) sampling: by type of media, for collected samples, for duplicated Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 21/30 samples, field blanks, background samples, and inter-laboratory split samples; definitions of collocated, replicated, and split samples and instructions regarding applicable measurement systems, including details on sample acquisition, homogeneity, handling, shipping, storage, preparation, and analysis; the need for the quantity and validity of data to meet enforcement and cost recovery actions; reviews of internal laboratory QA/QC, including surrogate and matrix spikes, method blanks, and duplicate or replicate runs, keeping the level of required analytical support in perspective; reviews of other parameters, such as the effects of media variability, method detection limits, and definitions of data qualifiers and details on their interpretation and use.” “C.1.2. Quality Assurance / Quality Control: Data evaluated and used to make health assessment determinations… must meet QA/QC criteria. Quality assurance (QA) programs assure the reliability and accuracy of data. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires the development of a QA plan for all tasks involving environmental measurements… Quality control (QC), an integral part of a QA plan, is the aggregate of activities and procedures designed to ensure attainment of prescribed quality standards for monitoring and measurement data. Quality control methods include the following: blind and identified standards analysis; multiple samples (a general term referring to any of the following types of samples: sample blanks, duplicate samples, split samples, and spiked samples); calibration of analytical equipment; and statistical design and evaluation…” “…A data review summary, prepared by the EPA Regional Laboratory staff, documents the validation of sample holding time, instrument performance, calibration, blanks, surrogate recovery, matrix spike recovery, and compound identification. It includes documentation of actions taken to resolve data quality problems and an overall assessment.” “When those documents are not available, the investigator should assume the data may not meet QA/QC criteria. Health assessments based on data that do not meet QA/QC criteria should include a disclaimer that acknowledges the use of possibly unreliable data and, therefore, the possibility of reaching inaccurate conclusions in the health assessment. Once familiar with data requirements for performing the health assessment, the investigator needs to review field and laboratory data.” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 22/30 “C.3.2. Detection Limits: Detection limits are the lowest quantifiable concentrations that can be determined and are affected by several factors, such as: analytical instrument, analytical method, sample matrix, and laboratory procedures… The reporting limit is of most importance to the investigator performing a health assessment and should be recorded in the data for every analyte concentration level.” “C.3.3. Data Validation: Data validation identifies invalid data and qualifies the usability of the remaining data. This should only be done by trained individuals with appropriate technical expertise. Nonetheless, the investigator should be familiar with validation practices and their impact on the data. Data validation is a series of performance checks and decisions on analytical procedures, calibration, instrument detection limits, QC samples, out-of-control events and corrective actions, and data evaluation and reduction. Considerations in determining the validity of the data from collected samples include the specificity and sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of the analytical procedure employed.” “The data user must keep the level of concern and the end use of the data in mind when reviewing precision and accuracy information. In some cases, even data of poor precision and/or accuracy may be useful. For example, if all the results are far above the level of concern, the precision and accuracy are much less important. However, when results are close to the level of concern, precision and accuracy are quite important and should be carefully reviewed. If results have very good precision but poor accuracy, it may be acceptable to correct the reported results using the percent recovery or percent bias data. Comments: It is worthwhile to note that in the entire “Pre-Decision Document”, the only reference to any aspect of data QA/QC or anything discussed in Appendix C is the statement: “Validating human exposure to ambient releases of diisocyanates requires a combination of air screening and sampling tools and biological monitoring.” It is a basic tenet of health affects studies that the first step in the study is to determine exposures. If QA/QC is ignored, which it has been by ATSDR, for the determination of exposure of the population, then no correlation or causal link can be established in the chain because a key step in the chain has been broken. This is the case in this study: Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 23/30 1. Plant emissions 2. Emission transport 3. Exposure of population 4. Development of biologic changes 5. Adverse health effects. Objective evidence exists that demonstrates conclusively that in the low parts-per-billion range of TDI concentrations, there are very strong effects on paper tape-based TDI monitors that may cause false positive (false alarm) readings. These are the presence of: Oxidizers, such as nitrogen oxides and ozone Engine and vehicle exhaust Cigarette smoke High humidity Tape age Exposure to light None of these known and published factors were taken into account by ATSDR. In fact, the 5 partsper-billion “hit” level chosen by ATSDR is prone to false positive artifacts. How can you tell? It is easy. When there is a “hit” the tape must be examined for the color of the spot. Basically, the problem is that this type of monitor has a chemical-impregnated paper tape. Upon exposure to TDI, it turns pink. Upon exposure to certain other materials, it turns other colors. However, the instrument does not know one color from another. Instead, it looks for decreases in reflectance of light from a light source in the instrument. A darker spot reflects less light, almost regardless of color. So, if you take this instrument out of the workplace and take it into the community with all sorts of other unknown contaminants at unknown concentrations, the instrument will show a noisy baseline that will, inevitably, spike above the "non-detectable" level, and inevitably, will spike above an arbitrary trigger point in the low ppb range. If you want to exclude all of the other contaminants from cross-reacting and giving false-positives, you must [1] monitor continuously for each of those contaminants, and [2] know the quantitative relationship among all of those factors. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 24/30 Not only that, but if the tape sits in the instrument for too many days before, during or after operation, it changes color and is no longer valid either for use or for examining the spot colors after the fact. ATSDR has apparently not taken this into account. An inquiry on this matter was written to ATSDR by the Polyurethane Foam Association (PFA): “We understand that the protocol for this project called for identifying whether any reactions on the paper tape testing devices are actually TDI. To have a reliable test, it is important that confirmation of the presence of TDI and source identification must occur. With respect to identifying that TDI was detected, it is our understanding that ATSDR would use the Omega Iso-Chek detection instrument to confirm findings recorded on paper tape used with Zellweger Analytics Single-Point Monitors (SPM). For reliable results, the Zellweger devices must be manned 24 hours a day or fitted with an alarm device to identify readings above 5 ppb and to cause immediate collection of Iso-Chek air samples. It is well known in the scientific community and stated emphatically by Zellweger Analytics that paper tapes are subject to interference from common outdoor pollutants including chemicals found in gasoline and diesel engine exhaust. It has also been established that the tape media is sensitive to direct light, humidity, dirt, dust, and emissions from sanitary sewers and loses reliability with age. Color shifts are more likely to occur the longer the tape remains in the testing instrument. Allowing exposed tape to remain in SPM instruments for up to five days may negate any possible scientific conclusions as to what types of emissions are detected and their concentrations in the area.” It is evident and true that a “hit” above 5 ppb on the continuous paper tape monitor cannot be confirmed through the use of the Iso-chek sampler because by the time the “hit” is detected by the paper tape monitor, the TDI concentration transient may or may not have already passed. Therefore, activating the Iso-chek sampler after the fact may or may not detect any TDI, which would prove nothing. The clock time and the sample averaging time will be different for the two methods. During the Trinity-Glenola study, ATSDR reported all positive Iso-chek and paper tape instrument “hit” results as correct, whether they were correlated or not. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 25/30 Also, the with respect to the Iso-chek samples, we understand that duplicate samples and a field blank QC sample will be taken. That is good. However, the Manual requires that additional quality control procedures be utilized: “C.1.2. … Quality control methods include the following: blind and identified standards analysis; multiple samples o (…sample blanks, duplicate samples, split samples, and spiked samples); calibration of analytical equipment; and statistical design and evaluation…” “A data review summary… documents the validation of: sample holding time, instrument performance, calibration, blanks, surrogate recovery, matrix spike recovery, and compound identification. It includes documentation of actions taken to resolve data quality problems and an overall assessment.” No such data was taken, analyzed or considered for either the paper tape or the Iso-chek samples at Trinity-Glenola. Will those samples be taken for the Iso-check? Will the QC be performed as required by the Manual? Reports have already been given that paper tape colors are inaccurate, that instruments are unattended for weeks at a time, and that Iso-Chek samples will not be taken to confirm paper tape readings prior to the reaching of conclusions about exposure of the population to TDI from the FPF plants. Instead, the ATSDR must follow its own rules: “When those documents are not available, the investigator should assume the data may not meet QA/QC criteria. Health assessments based on data that do not meet QA/QC criteria Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 26/30 should include a disclaimer that acknowledges the use of possibly unreliable data and, therefore, the possibility of reaching inaccurate conclusions in the health assessment.” In addition, except for one case, there was no co-location of paper tape monitors to measure replicability of readings. Furthermore, there is apparently no standard procedure on how to deal with suspected false positive paper tape readings, since at one plant the tape color changes were investigated and correlated with suspected high readings, and at another plant the paper tape itself was never reviewed but the digitized instrument data was accepted without question. In no case was there an investigation into the effects of environmental conditions or suspected non-TDI air contaminants. Lessons Learned: No consideration has been given to the QA/QC requirements prescribed in the Manual. None of the data that has been gathered to date should be used. 4. Manual - Chapter 8. “Determining Conclusions And Recommendations” “The final task in preparing a health assessment is to determine conclusions about the health implications associated with the site and to prepare parallel recommendations…” “Section 8.1.1. Determining Conclusions: In selecting the appropriate health hazard category, the assessor must consider the total body of information available for the site. Some of the important factors that must be weighed in the analysis include these: presence of completed or potential exposure pathways; on-site and off-site environmental contaminant concentrations; potential for multiple source exposures…” “8.1.2. Conclusions about Insufficient Information: Gaps in environmental characterization data or the lack of sufficient human health information may have been identified during the health assessment process. These data gaps should be reported in the Conclusions section of the health assessment.” Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 27/30 Comments: Exposure pathways have not been completed, on-site and off-site contaminant concentrations have not been determined, and the gaps in the environmental characterization data are so egregious that the project should be stopped. 5. Manual – Chapter 9. “Health Assessment Format” “9.1. SUMMARY: The Summary should be a concise synopsis of the health assessment and should state the following: site location, including nearest city or town, county, and state; contaminants that drive the selection of the conclusion categories "urgent public health hazard" and "public health hazard;" exposed populations; community health concerns; populations at special risk; completed exposure pathways; potential exposure pathways; health effects in exposed populations; conclusions about the public health category assigned to the site; urgency of the site's public health implications; and recommendations.” “9.4.1. On-Site Contamination: The On-Site Contamination subsection should define "on site" and discuss contamination within the site's boundaries. The text should discuss the following factors: sampling dates; spatial distribution of sampling locations; concentration changes over time (if relevant); medium-to-medium differences; and sample design and representativeness.” “…Footnotes can be used to clarify entries in the table or to denote data problems (e.g., quality assurance and quality control)… The assessor should discuss whether or not the sampling design and the number of samples adequately characterize on-site and offsite contamination. The text should identify deficiencies in sample design and number Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 28/30 for each media and should discuss how these deficiencies affect the analyses, conclusions, and recommendations in the health assessment. “9.4.2. Off-Site Contamination: Off-site contaminants of concern should be presented using the format for on-site contaminants. All contaminants identified in the on-site subsection should be included in the off-site subsection.” “9.4.3. Quality Assurance and Quality Control: QA/QC information should be available... QA/QC information should be used to determine whether the analytical techniques are adequate, the environmental data are representative, and the environmental media sampled are relevant… Every effort should be made to obtain QA/QC information. Absence of QA/QC information should be explicitly noted in this subsection of the health assessment. When QA/QC information cannot be obtained or does not exist, the health assessor needs to discuss the uncertainty and the limitations of the data and the effect the uncertainties and limitations have on the analyses, conclusions, and recommendations. The assessor may use or expand on the following qualifier: "In preparing this health assessment, ATSDR relies on the information provided in the referenced documents. We assume that adequate quality assurance and quality control measures were followed regarding chain of custody, laboratory procedures, and data reporting. The analyses, conclusions, and recommendations in this health assessment are valid only if the referenced documents are complete and reliable." “9.5.1. Completed Exposure Pathways. In addition to the exposure pathway, the assessor must also evaluate… whether or not the available data and information are sufficient to adequately characterize the five elements of the exposure pathway. The assessor should pay special attention to environmental conditions. Health assessors should determine if: sample location and number are representative of on-site and off-site contamination, analytic techniques are appropriate for the contaminants, environmental data are sufficient and relevant, and media sampled are appropriate. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 29/30 The text should explain deficiencies in these areas and indicate media that have not been sampled. This discussion should concisely indicate how these deficiencies affect the analyses, conclusions, and recommendations. A more elaborate discussion is acceptable when the assessor believes that data gaps prevent conclusive discussion of public health hazards.” “9.6.1. Toxicologic Evaluation. The text should include discussions explaining health effects according to biological plausibility: route of exposure, duration of exposure, exposed dose, dose-response relationships, and variation in pharmacokinetics.” Comments: This report shows that the ATSDR study in North Carolina has not proceeded in a systematic manner. Many of the issues of primary importance to such studies, most of which have been identified in the Trinity-Glenola case (Appendix A), appear to be almost completely or totally absent. There is no data that indicate that an attempt was made to correlate results of air sampling or monitoring with local meteorological conditions. In fact, the evidence that is presented indicates that there was no such correlation. It is a rule in causal analysis that correlation does not prove causation. It is also a rule that lack of correlation does disprove causation. This is one of the fatal weak links in the study to date. A complete understanding of all sources of environmental contaminants provides the foundation of any exposure assessment. It is dangerous to begin sampling prematurely before this understanding is gained. Based on available information and the ATSDR Manual and the Protocol, it appears that this foundation was not well constructed prior to executing the sampling program. Key components of the initial steps of identifying sources and exposure pathways were either not performed or were performed post facto. Due to the central role that biological monitoring will play in this case, it is improper to begin the initiation of biological monitoring based on incomplete, inaccurate, and mis-interpreted environmental exposure results. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016 30/30 No toxicological evaluation (Manual section 9.6.1) can take place when unknown factors include the duration or exposure-dose of the “exposed” and “control” populations. Despite sampling efforts to date, ambient air sampling results provided by the ATSDR-NCDHHS neither demonstrate, nor in any systemic or non-systematic manner confirm that fence line TDI concentrations were measurable, much less in violation of State of North Carolina standards. Furthermore, it is not demonstrated, based on the current state of understanding of TDI-related exposure issues, that fence line TDI concentrations present a public health risk, are correlated with asthma in the community, or are casually linked to asthma or any other adverse health effect. Lessons Learned: This project should be stopped until an impartial peer-review panel evaluates the design of the study, and oversees its implementation and analysis of the data. IV Recommendations 1. This study should be stopped immediately. 2. Data gathered in this study should be discarded. 3. An independent policy review should be instituted to determine the necessity to perform a study of diisocyanate-using industries, and to decide on the governmental body appropriate for the implementation and/or oversight of such a study. 4. If such a study is deemed necessary, an NIH-quality independent study panel, with stakeholder representation, should develop an R-01 quality RFP for such an investigation. 5. Such a grant should be funded at levels appropriate to the scope of the project so the project can be conducted in a scientific and reliable manner. Levine – PFA 2/12/2016