TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture 1. LANGUAGE AS A MEANS OF

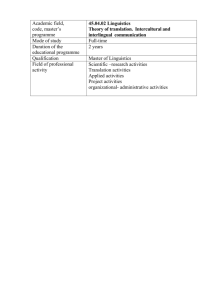

advertisement