Labour And Birth In Water 467

advertisement

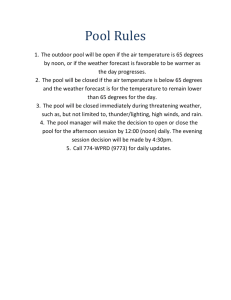

Labour and Birth in Water Contents Section 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0 8.0 Heading Background 1.1 Maternal benefits of water for labour / birth 1.2 Neonatal outcomes Page 2 Suggested criteria for use of the birthing pool Indications to leave the pool Health and Safety Preparation for water labour/birth Equipment needed Preparation of the pool 3 Pain relief for women using the birthing pool Care of the woman during labour First stage of labour Second stage of labour Third stage of labour Specific considerations 8.1 Group B haemolytic strep 8.2 Support of the woman in the pool 4 3 3 4 5 5 7 8 9 8.3 Emergency situations Maternal collapse Shoulder dystocia Cord snapping 8.4 Suturing 9.0 10.0 11.0 12.0 Appendix A Appendix B Training Monitoring Compliance Evidence Base Provenance Temperature Guide Evacuation Policy 1 1.0 Background The purpose of these guidelines are not to restrict practice but to strengthen good midwifery care and enhance ways in which a midwife can safely and to the best of her ability support a woman choosing to labour and / or birth in water. Water has long been known for its therapeutic value. The use of water in midwifery encompasses not only the birth but also the labour. Immersion in water raises the level of endorphins so that the body can relax and enjoy the analgesic effects of water5. The use of water during labour and birth appeals to women, their birth partners and midwives, particularly those striving for a woman-centred, intervention free, ‘normal’ experience15. “The statistical significant reduction in the rate of epidural / spinal / paracervical analgesia suggests that water immersion during the first stage of labour reduces the need for this invasive, pharmacological pain mode of analgesia, which disturbs the physiology of labour and is associated with iatrogenic interventions.”5 Every woman without major complications should be offered the opportunity to labour and give birth in water in the same way other forms of analgesia are offered offered. 1.1 Maternal benefits of water labour / birth Evidence suggests that water immersion during the first stage of labour reduces the use of epidural / spinal analgesia. A systematic review based on data from six trials showed significant reduction in the incidence of epidural and spinal analgesia 22. This review also found that for women at low risk of complications, labouring in water reduced the likelihood of needing an instrumental vaginal delivery. Water reduces adrenaline and catecholamine’s, therefore increasing a woman's own natural endorphins and oxytocin, therefore shortening the length of labour. Increased adrenaline levels can inhibit labour and excessive levels of catecholamine’s may cause dysfunctional labour, decreased uterine tone, slower dilatation and resulting hypoxia17. The buoyancy of water allows the woman to move more easily than out of water. This has an effect on hormones alleviating pain and optimising the progress of labour. Women using water as a form of pain relief reported significantly less pain than those not labouring in water5. The ease of mobility offered through the use of the birthing pool may also optimise fetal position by encouraging flexion. A deflexed fetal position is often associated with in coordinate uterine contractions resulting in slow progress and a longer more painful labour. The benefits of being upright in labour include less pain, a shorter second stage, less assisted delivery and a decrease in abnormal fetal heart rate patterns. Water immersion reduces blood pressure due to vasodilatation of the peripheral vessels and redistribution of blood flow. Water immersion during labour increases maternal satisfaction and a sense of control10. A pool offers a woman an 2 environment where she can act instinctively and feel in control. Increased sense of control during childbirth leads to a greater sense of emotional well-being postnatally. 1.2 Neonatal outcomes There were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes for water births compared to uncomplicated births on out of water17. 2.0 Suggested criteria for use of the birthing pool for labour and / or birth Suitability for labour and birth in water will be agreed at the onset of labour following a full risk assessment as detailed in the “care of Women in Labour” Guidance. This is found at the start of the birth record and applies to women delivering at home or in hospital. The majority of identified risk factors will be a contraindication to labour and birth in water although carriage of Group B Streptococcus is not provided antibiotic cover is offered as usual18,24. Maternal choice Uncomplicated pregnancy, medical and obstetric history Gestation between 37+0 and 42 weeks Spontaneous onset of labour Cephalic presentation Singleton pregnancy Maternal weight under 100kg If spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM), no signs of meconium onset of labour no more than 24 hours after SROM. No maternal infection causing pyrexia Not had a previous shoulder dystocia requiring more than McRoberts (labouring in the pool can be an option following discussion with the woman). 3.0 Indications to leave pool at any time during labour The woman should be informed she may need to leave the pool if problems arise. Maternal request Meconium stained liquor Water contamination- vomit, diarrhoea Significant blood loss Concerns regarding fetal heart rate – if CTG subsequently re-assuring may return to pool if desires Prolonged first or second stage of labour Abnormal maternal observations Maternal pyrexia (defined as 38.0⁰C once or 37.5⁰C on two occasions 2 hours apart) If further analgesia (other than entonox) required 3 With reference to maternal pyrexia it is recommended practice to encourage fluids in order to avoid dehydration and possible hyperthermia. In cases of raised maternal temperature it is recommended to reduce the water temperature and depth of the water to facilitate the woman in losing body heat. It is also recommended to consider leaving the pool and when maternal temperature reduces the woman may return to the pool. There should be ambient room temperature and fans available. 4.0 Health and Safety The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust Moving and Handling policy to be adhered to at all times, including the emergency procedure for removing a collapsed woman from the pool. Furthermore the universal Infection Control Precautions must be adhered to at all times. Cleaning the pool: Use Suma Bac 10-15mls per litre of water, clean all surfaces of the pool including taps and plug. Leave for five minutes then rinse thoroughly with clean water until clear. Use new cloth every time the pool is cleaned. 5.0 Preparation for water labour/birth 5.1 Equipment needed Water thermometer Sonicaid, waterproof and battery operated Step for getting in and out of the pool Towels for woman and baby Sieve Mirror Ensure all equipment is cleaned. Clean thermometers with sani-cloths and sieves and mirror with chlor clean tabs. For homebirths the woman’s birth partner should take responsibility for assembly, inflation, filling and emptying of the pool and ensuring that the room is adequately ventilated and furnished for the comfort, health and safety of parents and staff. Provide the woman with a home water birth leaflet. 5.2 Preparation of the birthing pool The pool should be prepared to a depth comfortable for the labouring woman. The water should be deep enough to cover her abdomen and sufficient enough to facilitate mobility. The pool needs to be at least 50cms deep to achieve adequate buoyancy and to be deep enough to always cover the vertex especially in all fours position. This is why we do not advise women to give birth in the bath at home. During labour the water temperature should be adjusted to ensure maternal comfort. Water temperature should be maintained between 34 and 37⁰C for the first stage and 37 and 38⁰C for second stage It is very important not to overheat the water as it is thought this may cause vasodilatation leading to hypotension and cause fetal 4 tachycardia and fetal hypoxia because of the baby’s inability to regulate its temperature2. Pool temperature should be continuously monitored and documented in the birth record at least ½ hourly during labour. The water should be kept as clear as possible at all times, the sieve being used to remove any debris, to allow observation of the colour of the liquor and to note any excessive blood loss. 6.0 Pain relief for women using the birthing pool Immersion in water significantly reduces pain of labour. Encourage simple methods, relaxation, hypnobirthing and massage therapy. Entonox may be used under supervision as additional pain relief whilst in the pool. If intra muscular analgesia is required the woman must leave the pool. If however, the woman has been administered opiods in early labour and is not adversely affected i.e. drowsy and it is at least 4 hours from administration consideration can be given to the woman entering the birthing pool. This should be discussed with the woman, midwife and co-ordinator. 7.0 Care of woman during Labour 7.1 First stage of labour To ascertain maternal and fetal well-being: record on a MOEWs chart baseline observations of maternal condition: blood pressure, pulse, temperature and urinalysis Palpate abdomen to determine fetal lie and presentation auscultate fetal heart with self counting sonicaid. A vaginal examination may be performed to confirm the onset and stage of labour. It is the clinical judgement of the midwife to support the woman with analgesia options and review the plan for labour with the woman and her partner. Consideration needs to be made to use the pool in early labour to maximise the calming effect of the water. The water sometimes slows or stops labour if used too early. The woman’s wishes should be paramount. If the midwife caring for the woman feels it is too early to enter the pool a discussion should take place so that the woman can make an informed decision. Each and every situation must be evaluated and then judged and if contractions are strong and regular with either a small amount of dilatation or none at all the use of water can promote relaxation and subsequent facilitation of dilatation. When comparing early versus late water immersion during the first stage of labour, there is a significantly higher epidural rates in the early group and an increased incidence of augmentation of labour. The first hour following the woman entering the pool is when the effects of the water will 5 become apparent and if contractions space out or become less frequent it is advisable to suggest leaving the pool and encouraging mobilisation. Once in the pool monitor maternal and fetal well-being as is usual practice in normal labour (see LTH guidelines relating to the care of women in normal labour) If the maternal temperature exceeds 38oC on any one occasion or 37.5oC on 2 separate occassions, the woman must leave the pool. Cooling measures should be employed (see LTHT guidelines pyrexia in labour) and the delivery suite coordinator informed. Summary of observations in first stage of labour Observation Frequency Temperature Blood pressure (BP) Maternal pulse Fetal heart rate (FHR) hourly 4 hourly 1 Hourly Hand Held aqua Doppler machine for one full minute immediately after a contraction every 15 minutes half hourly and at each VE Colour of amniotic fluid Uterine contractions Duration strength & frequency Abdominal examination Vaginal examination Urine (test all specimens for ketones) Every 30 minutes 4 hourly 4 hourly encourage woman to a pass urine regularly and at least every 4 hours The woman should be encouraged to drink plenty of water whilst in the pool (recommended 1 litre per hour, and to leave the pool to urinate if she wishes. All urine output should be documented on the partogram. Water immersion vasodilates the woman and inhibits vasopression, so she requires more fluid intake and to urinate more often. A full bladder is to be avoided in labour because it obstructs fetal descent and may cause future urinary problems (see LTHT bladder care guidelines). Vaginal examinations can be performed in the birthing pool at the discretion of the midwife and consent of the woman. If for any reason the woman is out of the pool and the vertex is visible she may not re-enter the pool as contact with air may stimulate premature breathing16. If the woman is showing signs of the onset of the second stage it may be inappropriate to ask them to vacate the pool to perform a vaginal examination. If artificial rupture of the membranes is required due to slow progress this may be performed in the pool. In the majority of labours the membranes will rupture spontaneously in the first or second stage of labour. Amniotomy is an unnecessary intervention7, however, if you are certain that meconium is visible behind the membranes then the woman should vacate the pool for delivery. If meconium is suspected behind the membranes consider artificial rupture of membranes within the pool to confirm this. On rare occasions the membranes may not rupture. In these circumstances they usually 6 break as the head or shoulders are born. For those few baby’s that are fully born in intact membranes, guide the baby in the caul (amniotic sac) to the surface and tear the membranes between the chin and the neck7. 7.2 Second stage of Labour It is important to maintain the pool temperature between 37-38°C. If the water is less than 37⁰C this may stimulate the initiation of respiration before the baby reaches the surface. Pool temperature should therefore be recorded ½ hourly in the birth record. Observations in the second stage of labour Observation Frequency Temperature Blood pressure (BP) and Pulse Fetal heart rate (FHR) Half hourly 1 hourly Aqua handheld Doppler for one full minute immediately after a contraction every 5 minutes Uterine contractions duration frequency Abdominal examination Vaginal examination Urine (test all specimens for ketones) Every 30 minutes Prior to vaginal examination Offer hourly in active second stage As necessary (encourage woman to a pass urine every 2 hours) Encourage the woman to adopt the position most comfortable for her9,10,21. There should always be two midwives present for birth or a midwife plus either a student midwife or maternity support worker. Little intervention will be required during delivery. Pushing should be spontaneous, and is less likely to exhaust both woman and baby and prevent an imbalance between carbon dioxide and oxygen in the fetal / maternal circulation. If following a two hour passive second stage the woman has no urge to push, more directed pushing should be commenced. If the head is not visible after 30 minutes consider a vaginal examination to assess descent of the head and discuss further care / management with the co-ordinator. Traditional control of the head during crowning is not necessary. There should be no interference from the midwife. Immersion in water changes the skin elasticity and the counter pressure of the water enables the woman to push more steadily while the head crowns, thus allowing a spontaneous gentle birth. It is not necessary to palpate for the presence of the umbilical cord once the baby’s head is born. It can be loosened and disentangled as the baby is born if needed. The cord should never be clamped and cut whilst the baby remains under the water. The baby should be born completely immersed under water to prevent stimulation of respiration14,16. As soon as the baby is completely born lift the baby gently to the surface, ensuring the head of the baby emerges into air. As with any reflex, the longer it is maintained, the less intense the response. Long exposure to the diving reflex leads to episodic breathing, which eventually results in aspiration. The baby’s head must then stay out of the water with the body below the surface of the water to prevent cooling. Assessment of the baby should be according to normal labour protocol. 7 7.3 Third Stage of Labour Management and place of delivery depends on the woman’s wishes, i.e. physiological or active and also the confidence and skills of the midwife 3,8,20. However, if blood loss is within normal limits and antenatal haemoglobin, a physiological third stage may prove to be the least intrusive and the woman can remain in the pool for a longer period. 7.3.1 Active management Active management is always conducted out of the pool (see LTHT guideline “Care of women in labour”), The woman should leave the pool a maximum of 10 minutes after delivery. Routine observation of the woman should occur with third stage management, including her general physical condition as shown by her colour, respiration and her own report of how she feels and close monitoring of vaginal blood loss. 7.3.2 Physiological third stage out of the pool The cord should be clamped and cut when pulsation has ceased to allow the woman to leave the pool. It is important to keep woman and baby warm in skin to skin contact with the nipple to facilitate placental delivery(see LTHT guideline “Care of women in labour”), 7.3.3 Physiological third stage in the pool Exclusion Criteria – - Heavy blood loss Woman feels faint Delayed delivery of the placenta Baby requires resuscitation In the absence of complications there is no evidence to support removing women from the pool for a physiological third stage and in doing so this can interrupt crucial maternal / infant contact. This maintenance of privacy and contact with the nipple optimises oxytocin secretion. The early theoretical risk of water embolism has been dispelled and there are no documented cases of water embolism23. Physiological third stage in the pool may also be more successful as the cord remains intact which aids the physiological process6. With the woman sitting upright, rest baby with only their head above the level of the water at the level of the woman’s uterus. This prevents possible excessive transfusion to the baby and reduces heat loss. Baby suckling can be encouraged. Skin to skin contact, particularly direct contact with the nipple should be encouraged as this increases oxytocin levels which assist in the birth of the placenta. There is no need to divide the cord between woman and baby; the cord may be left unclamped until the placenta and membranes are expelled. There is only one documented case of neonatal polycythaemia following third stage of labour underwater1, and this can be prevented by following the above recommendation. 8 At any point if excessive blood loss is suspected then the woman should be asked to leave the pool, and active management considered. It is safe practice to clamp and cut the cord prior to assisting the woman out of the pool. A useful way to identify the extent of haemorrhage is to observe how dark the water is getting. Can you still assess skin colour of the woman’s thighs even though there is blood in the water? Blood loss should be estimated through clinical observation of maternal observations and how the woman feels. Maternal observations should be recorded every 15 minutes. Maternal tachycardia can be the first sign of an impending post partum haemorrhage. Physiological third stage can last up to 2 hours, however active management should be offered after one hour if placenta undelivered. 8.0 Specific considerations 8.1 Group B haemolytic streptococcus (GBS) Approx 1 in 4 women having a water birth unknowingly carries GBS, yet no significant differences in neonatal infections after water births compared to birth out of water have been reported18,24. As intravenous antibiotics are effective in reducing the transmission of GBS to the neonate, as long as there are no other risk factors, women should not be denied the use of the pool or the water birth that they desire because they have been identified as colonised by GBS during the pregnancy (MSU or HVS). . A waterproof dressing should be used for the peripheral cannula as it needs to be kept as dry as possible. Provided it is well sited and the woman assists with keeping her hand above the level of the water as much as possible a canula should not be an exclusion criteria for using water for labour / birth. Administration of intravenous antibiotics should be performed out of the pool. 8.2 Support of the woman while in the pool There are no contraindications to the birthing partner entering the pool in the first stage of labour to support the labouring woman. However, the partner must maintain decency by wearing swimwear or underwear. 8.3 Emergency Situations In the rare case of an emergency ask the woman to stand up and leave the pool if she is able to, if she feels unwell or faint she should be assisted onto the bed which can be moved next to the pool. 8.3.1 Maternal Collapse Summon help and raise the woman onto the evacuation seat using the net, move the bed next to the pool and transfer her onto it. Maintain the woman’s airway throughout (see appendix A for evacuation protocol). 9 8.3.2 Shoulder Dystocia If you anticipate a potential problem prior to or with the delivery of the head such as restitution, ask the woman to get into a squatting position while holding onto the bars. Pushing in this position may be all that is needed to aid birth of the baby as it uses the maximum dimensions of the pelvis. Call for a second midwife for the delivery. If delivery of the shoulders does not occur with maternal effort, Call for help immediately. Ask the woman to stand out of the water with one foot raised on the side of the pool or onto the emergency seat and attempt delivery. If the shoulders are still not born ask the woman to vacate the pool immediately while assisting her. If she is unable to move use the evacuation protocol. 8.3.3 Cord Snapping Cord snapping at any delivery is a rare event, but one that midwives need to be aware of, especially if the woman has delivered in the water. Recognition of this immediately prevents severe outcomes for the neonate6. Avoid traction on the cord and bring the baby up into the woman’s arms slowly. Be careful to avoid undue tension or resistance on the cord. Always check that the cord has not snapped and have cord clamps at hand just in case. 8.4 Suturing Suturing of perineal tears should be delayed for 1 hour unless bleeding excessively from the tear. This is to allow water to drain from the tissues. 9.0 Training Before undertaking a waterbirth, midwives must attend a full training session, witness and assist at a water birth and then undertake a waterbirth with another trained midwife before embarking on a birth independently. Following initial training there should be an update every 3 years which will normally be a short revision during mandatory training. 10.0 Monitoring compliance An audit form should be completed for all women who use the pool while in established labour. Data will be analysed every 2 years in accordance with the Maternity Services Audit Plan. Auditable criteria include: Number of women birthing in water Observations performed in all stages of labour Management of the third stage of labour Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage Incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes 10 Audit results will be presented at the Women’s Services Clinical Governance and Audit meeting and an action plan developed as necessary. A lead will be appointed for monitoring of the action plan, including re-audit, and the status of the action plan reported to the Women’s Services Clinical Governance and Risk management Forum quarterly. Audit results will be included in the Maternity monthly risk management report and any resulting changes disseminated via the Maternity Services Forum, Team Leaders Forum, Supervisors Forum. 11 11.0 Evidence base 1. Austin, T; Bridges, N; Markiewicz, M and Abrahamson, E. 1997. Severe neonatal polycythaemia after third stage of labour underwater. Lancet. 350, pp 1445-1450. 2. Balaskas, J. 1994. Clinical guidelines for a hospital water birth pool facility. UK. [Internet] Available from: http://www.activebirthcentre.com/pb/wbguidelinesformidwives.shtml [Accessed 6th June 2011]. 3. Begley, CM. 1990. A comparison of ‘active’ and ‘physiological’ management of the third stage of labour. Midwifery. 6, pp3-17. 4. Burns, E and Kitzinger, S. 2005. Midwifery Guidelines for the Use of Water in Labour. Oxford, Oxford Brookes University. 5. Cluett, ER and Burns, E. 2009. Immersion in water in labour and birth (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 6. Cro, S and Preston, J. 2002. Cord snapping at waterbirth delivery. British Journal of Midwifery. 10. (8). P 494-497. 7. Dickson, L. 2003. Birth in a caul: a discussion on the role of amniotomy in physiological labour. Newzeland College of Midwives Journal. 29, pp 7-10 8. Dunn, PM. 1996. The placental venous pressure during and after the third stage of labour, following early cord ligation. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 73, pp 747-756. 9. ENKIN, M., KEIRSE, M., NEILSON, J., et al. (2000). A Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. 3rd ed. London: Oxford University Press. 10. ROSSER, J., (2000). Women's position in second stage. The Practising Midwife, 3 (8), 10-11. 11. Garland, D. 2000. Waterbirth an attitude to care. Second edition, Edinburgh, Books for Midwives. 12. Garland, D. 2002. Collaborative waterbirth audit - supporting practice with audit. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 12. (4). 508-11. 13. Garland, D. 2006. “On the crest of a wave” Completion of a collaborative audit. Midirs Midwifery Digest. 16(1), pp 81-85. 14. Garland, D. 2010. Gentle birth, the water birth concept. Midwife expert. Study day November 2010. 15. Green, JM; Coupland, VA and Kitzinger, JV. 1998. Great expectations: A prospective study of womens expectations and experiences of childbirth. Second edition. Cheshire, Books for Midwives. 16. Johnson, P. 1996. Birth under water – to breathe or not to breathe. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 103(3), pp 202-208 17. Ohlsson, G; Buchhave, P, Leandersson, U, Nordstrom, L; Rydhstrom, H and Sjolin, I. 2001. Warm tub bathing during in labour: maternal and neonatal effects. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 80, pp 311-314. 18. Plumb, J; Holwell, D; Burton, R and Steer, P. 2007. Water birth for women with GBS: a pipe dream? The Practising Midwife. 10(4), pp 25-28 19. Richmond, H. 2003. Womens experiences of childbirth. Practising midwife. 6(3), pp26-31. 12 20. Rogers, J; Wood, J; McCandlish, R; Ayers, S; Truesdale, A and Elbourne, D. 1998. Active vs expectant management of the third stage of labour: the Hinchingbrooke randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 351, pp 693-699. 21. Roodt, A and Nikodem, VC. 2005. Pushing / bearing down methods used during the second stage of labour. (Protocol) The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews2002. The Cochrane Collaboration John Wiley & Sons. 22. Taha, M. 2000. The effects of water on labour: a randomised controlled trial. Cited in Cluett, ER and Burns, E. 2009. Immersion in water in labour and birth (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 23. Wickham, S. 2005. The birth of water embolism. The Practising Midwife. 8 (11), pg 37. 24. Zanetti-Dallenbach, R; Lapaire, O; Maertens, A; Frei, R; Holzgreve, W and Hosli, I. 2006. Waterbirth: Is the water an additional reservoir for Group B Streptococcus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 273, pp236-238 12.0 Provenance Authors: Debbie Daly; Coral Morby (midwives); Gail Wright (team leader). Review: Originally published 2004 by G Wright and updated July 2006 and June 2008 Next review: Sept 2014 Person responsible for review: G Wright (team leader) Target patient group: any woman booked to deliver in LTHT or at home choosing to labour/birth in water Target professional groups: all healthcare professionals involved in intrapartum care 13 Appendix A - Temperature Guide Maternal Temperature Pool Temperature First stage To be documented hourly Second stage To be documented ½ hourly To be maintained between 34 - 37⁰C To be documented ½ hourly To be maintained between 37 - 38⁰C To be documented ½ hourly Appendix B - Evacuation Policy 1) Call for help Add water to the pool Keep the woman’s head above the water 2) FOUR people required Place trolley next to pool Roll net under 3) Lift woman onto safety seat 4) Slide onto bed / trolley 14 Guidelines for Immersion in Water for Labour and Birth Author(s) Debbie Daly, Coral Morby and Gail Wright Contact name Approval process Debbie Daly and Coral Morby Maternity Services Clinical Governance First Issue Date Version no: Review Date: Approved by May 2004 by G.Wright Updated by D. Daly and C.Morby 2011. 3.1 Updated July 2006; June 2008, Sept 2011 Next review : January 2014 Maternity Services Clinical Governance and Risk Management Forum September 11 Consultation Process Maternity Services Guideline Group / Maternity Services Forum, Maternity Services Clinical Governance and Risk Management Forum / Paediatricians / Team Leaders / Supervisors of Midwives Scope of guidance Clinical condition Women receiving intrapartum care Patient Group Dissemination All pregnant women receiving intrapartum care within the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust All Health Care Professionals involved in the provision of intrapartum care within the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust All Midwives – hospital and community midwives Obstetricians Lead Clinician Head of Midwifery Matrons Clinical Midwifery Team Leaders Via Risk Management Midwife Audit and Monitoring Will be carried out in accordance with Maternity Services Audit Plan Professional Group Distribution List Equity and Diversity Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust believes in fairness, equity and above all values diversity in all dealings, both as providers of health services and employers of people. The Trust is committed to eliminating discrimination on the basis of gender, age, disability, race, religion, sexuality or social class. We aim to provide accessible services, delivered in a way that respects the needs of each individual and does not exclude anyone. By demonstrating these beliefs the Trust aims to ensure that it develops a healthcare workforce that is diverse, non discriminatory and appropriate to deliver modern healthcare. 15