Model final essay

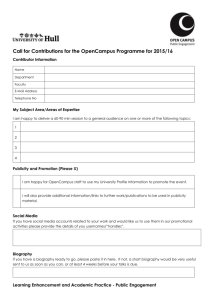

advertisement

POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 1 A Foucauldian Analysis of Portrayals of Female Docility in Popular vs. Critical Media A Correlation to Female Docility in Higher Education Final Essay grade A+ SOSC 3930: University and Society Dr. Indhu Rajagopal POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 2 Abstract In this paper, I will argue that women in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies are turned into Foucault’s (1995) “docile bodies” through ‘disciplinary power.’ The body is normalized, individuated, surveilled and objectified through social power that disciplines and controls it. Literature on the experiences of university women in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies show that the women in these fields endure gender inequities. In my analysis, I will explore female representations of popular vs. critical media to examine the influence of media as the apparatus of the disciplinary power. Persuasive and pleasurable representations of women’s ‘normalized’ behaviour and obligatory docility in popular media subjectivize and discipline the female body. In contrast, critical media expose the disciplinary inscription on the female body caught in the power matrix of ‘masculine’ fields. Relevant Literature on the Process of Female Docility Individuating and Normalizing Female Bodies Popular media disseminates qualities of stereotypical ‘normal’ gender behaviour (Eschholz et al., 2002, p. 299). This can be seen in popular media representations of science as a male field (Long et al., 2001, p. 265) and males as socially dominant (Eschholz et al., 2002, p. 322; Lauzen & Dozier, 2005, p. 444). These types of ideas can decrease women’s assurance of their capabilities (Herring & Marken, 2008, p. 234) and lead to the understanding that males are more competent than females in certain subject matters (Herzig, 2004, p. 392; Steele et al., 2002, p. 49). Foucault’s notion of individuation is useful to explore how women are excluded and subjected to normalization in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies. Foucault (1984a) sees individuation as a way to control individuals who defy norms (p. 218). Normalization POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 3 encompasses how individuals come to accept and internalize social norms (Bernauer & Mahon, 1994, p. 143 & p. 151). Individuation and normalization can be seen to operate together as people are separated from the population as unique and then classified based upon their actions (Foucault, 1984c, p. 195). The literature reveals that women in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies experience normalization and individuation. For example, Herzig (2004) argues that professors of natural/physical sciences favour mentoring male students (p. 380). McKinley (2005) asserts similar findings on reports of Maori female scientists who argue that due to their culture and gender, they are less respected as scientists (pp. 488-489). Furthermore, there is an implication that male students represent the norm. More specifically, female contributions in graduate education are not as acknowledged as male contributions (Wall, 2008, p. 220) and feminist scholarship is positioned outside of mainstream academia (Hart, 2006, p. 56). The Surveillance and Objectification of Females In addition to experiences of normalization and individuation, women in higher education can also be perceived to experience surveillance and objectification. To be sure, surveillance refers to the watching of bodies (Foucault, 1984c, p. 192), which allows for power relations to enter bodies (Foucault, 1984b, p. 180). Objectification encompasses individuals being treated as bodies controlled by power, instead of active agents (Foucault, 1984c, p. 188). Notably, scholars find that female students experience gender discrimination (Morrison et al., 2005, p. 158; Steele et al., 2002, p. 49). This implies that women are being watched. Mottarella et al. (2009) also discusses the “good mother stereotype” where women who go back to higher education after having children are judged (p. 230). These forms discrimination and judgment can be seen to objectify females as assumptions about their abilities (Steele et al., 2002, p. 49; Morrison et al., POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 4 2005, p. 158) and character (Mottarella et al., 2009, p. 230) are being derived from their gendered bodies. Control and Disciplining: Female Docility Following objectification, individuals become controlled and then disciplined bodies (Rajagopal, Lecture 5, October 27th, 2009). Women face challenges in higher education including gender discrimination and judgment (Morrison et al., 2005, p. 158; Mottarella et al., 2009, p. 230; Steele et al., 2002, p. 49). It is argued that such challenges can be looked at as punishments to control female advancement (Morrison et al. 2005, p. 154). One then becomes disciplined and docile by regulating one’s own behaviour according to established norms (Rajagopal, Lecture 5, October 27th 2009). To be sure, scholars recognize that female students are receiving more post-secondary degrees than male students (Blackhurst & Auger, 2008, p. 149). Further, Cho (2006) connects this to high levels of success for female students at the secondary level of education (p. 450). Despite this, gender inequalities remain prominent (Bradley, 2000, p. 1). Women are not necessarily challenging the status quo, but instead have been turned into docile bodies as they regulate their own behaviour according to how they are perceived (Morrison et al., 2005, p. 154). Evidence of this docility includes a disinclination to acknowledge gender discrimination (Middleton, 2005, p. 522; Morrison et al., 2005, p. 150), a lack of self-belief at higher levels of education (Barata et al., 2005, p. 239), and a discontinuation of studies (Herzig, 2004, p. 392). Potential Solutions The literature is inconclusive with regards to solving gender inequalities for women in higher education. Suggestions include introducing alternative ways of thinking that promote female capabilities (Oswald, 2008, p. 201). This, however, may evoke another way in which to POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 5 control female bodies. Other scholars advocate for a space for females to speak about their experiences (Barata et al., 2005, p. 243), yet paradoxically education is said to be lacking room for critical subject matter (Middleton, 2005, p. 524). Overall, a review of the literature reveals that despite increasing participation of females in higher education, gender inequalities remain prominent for women in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies. The Influence of the Media as an Apparatus of Disciplinary Power The inconsistency of the literature in regards to solving gender inequalities points to the necessity of further investigations. Studies of popular media representations have been conducted with a focus on gender stereotypes (Eschholz et al., 2002; Lauzen & Dozier, 2005; Long et al., 2001). I will build on the existing literature by investigating female representations in popular vs. critical media to examine the influence of media as the apparatus of Foucault’s (1995) ‘disciplinary power.’ Using the same conceptual themes from the literature review, I will link female docility in higher education to media representations of female docility. My analysis of popular media will focus on processes of obligatory docility in the film The Proposal (2009) and season one of the television series Nurse Jackie (2009). A television advertisement and song lyrics will also be used. I will contrast popular media with critical media in the form of cartoons. Individuating and Normalizing Female Bodies The above literature review discussed the ways in which females in higher education experience normalization and individuation. Despite initial appearances to the contrary, The Proposal (2009) and Nurse Jackie (2009) depict these processes of normalization and individuation. On the surface, The Proposal (2009) appears to challenge traditional gender representations by presenting Margaret, a successful female book editor, with a male assistant named Andrew. Nurse Jackie (2009) also features Jackie as a woman who maintains a POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 6 demanding job in medicine and a family life. Eschholz et al. (2002), however, argue that the social power of the male continues to be normalized in popular media (p. 322). With a more nuanced look, the findings of Eschholz et al. (2002) are confirmed in both The Proposal (2009) and Nurse Jackie (2009). In The Proposal (2009) Andrew’s position as a male assistant is utilized for comedic purposes, with his family making jokes about his lack of ambition. The fact that Margaret has two male bosses, however, is presented as an aside and not emphasized in the same manner. The Proposal (2009) thus serves to normalize male dominance in the workplace by highlighting Margaret and Andrew’s working relationship to ignite laughs, while simultaneously ignoring Margaret’s relationship with her male bosses. This implies that Margaret and Andrew are deviating from the norms of the workplace hierarchy. In addition, Margaret is depicted as a professional and social ‘outsider.’ Margaret’s coworkers find her highly unapproachable, and it is also revealed that she maintains no relationships outside of work (The Proposal, 2009). The television series Nurse Jackie (2009) similarly serves to normalize male dominance in the workplace, and individuate females as outsiders. The nurses are mainly female, while the majority of doctors are male. In addition, Jackie is unable to integrate her public working life and private home life. She maintains an extreme separation between these two spheres and hides the fact that she has a husband and children at her workplace. In fact, Jackie goes so far as to remove her wedding ring each day before work. She further carries on a secret affair with a male coworker and does not reveal her family life to him for the majority of the season (Nurse Jackie, 2009). Jackie is thus individuated an outsider in both realms of her life since she is never able to express her true self. Instead of this being highlighted as problematic, the separation of her lives is utilized for dramatic purposes to promote suspense (Nurse Jackie, 2009). POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 7 Presenting individuation and normalization as pleasurable in the form of a comedy or drama is dangerous. According to Stern (2005), it is possible that media portrayals of teenagers have some bearing on adult’s opinions of teenagers in reality (pp. 33-35). Using Stern’s (2005) analysis, the normalization of male dominance and the individuation of females may have some bearing on people’s perceptions of women in masculine disciplines. In contrast, critical media encourages one to recognize normalization and individuation by poking fun at popular representations. For example, a cartoon features a table dominated by male executives who mock the lone female’s experience of gender inequality (See Appendix A). Another cartoon portrays a female executive who answers her own phone and is assumed to be a secretary (See Appendix B). Notably, Giroux (2002) argues that students should be taught to think critically in higher education (pp. 15-16). Critical media, moreover, promotes the type of practice that Giroux (2002) asserts is necessary for democracy (pp. 15-16). In exposing the normalization of male work hierarchies and the individuation of female bodies through humour, critical media forces one to question, rather than blindly consume popular representations. The Surveillance and Objectification of Females Eschholz et al. (2002) find that popular media objectifies women (p. 323), and reproduces social relations of dominance (p. 325). Freedman (2003) also references the objectification of females in popular media (pp. 85-86), while Aubrey (2006) notes the pervasiveness of such objectification in popular media (p. 384). This is evident in both The Proposal (2009) and Nurse Jackie (2009), as the female characters are subjected to surveillance and objectification. In The Proposal (2009) it is revealed that Margaret will face deportation due to an expired visa. She coerces Andrew into marrying her so that she will not be deported and keep her job. Margaret then travels to Alaska with Andrew to reveal their marriage plans to his family. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 8 As a result of her plot, Margaret is constantly watched and evaluated by her bosses, government officials, and Andrew’s family. She further conforms to the ways in which these various parties see her. For instance, Margaret adopts a confident and firm demeanor with her bosses. She then switches to a gentler demeanor in front of government officials and Andrew’s family to convince them of the authenticity of her love for Andrew. In addition, Margaret also experiences objectification through her coworkers’ gendered comments. They refer to her as “it” “the witch” and “Satan’s mistress” (The Proposal, 2009). The comment of “it” is particularly problematic as it implies that a successful women cannot be fully female. Jackie also experiences surveillance and objectification in Nurse Jackie (2009). She receives judgment from her daughter who tells her to stay home more often (Daffodil, 2009; Nose Bleed, 2009). Jackie’s gender takes centre stage in this form of surveillance. In essence, her husband also works outside of the home, yet never receives such judgment from their daughter. This evokes Mottarella’s (2009) discussion of the “good mother stereotype” where women who go back to higher education after having children are similarly judged (p. 230). In addition, Jackie experiences objectification as her abilities at work are linked to her gendered body. A coworker tells her that nurses are supposed to be compassionate, while doctors lack emotion (Pilot, 2009). Since most of the nurses are female and most of the doctors are male, this comment connects one’s qualities and character to gender. The objectification of female bodies is further reinforced in an advertisement for the television program Californication. A male is displayed in the centre of the advertisement, with the bodies of female students surrounding him. The faces of the female students are not shown and they are wearing very little clothing (See Appendix C). In effect, this advertisement places the emphasis on females’ bodies rather than on their abilities or knowledge as students. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 9 Popular media is thus revealed to subject female bodies to surveillance and objectification. Aubrey (2006) finds that this can lead to one objectifying oneself (p. 381). Interestingly, Leone et al. (2006) note that individuals feel they are less influenced by the media than others (p. 265). At the same time, however, Freedman (2003) finds that pre-service teachers are uncritical of popular cultural messages (p. 93). As such, Freedman (2003) reveals that media does influence one’s beliefs despite feelings of immunity (p. 94). In this way, popular media promotes uncritical acceptance of the surveillance and objectification of female bodies. Critical media, however, makes the surveillance and objectification of females in masculine fields explicit. One cartoon features two men evaluating a woman to determine if she is suitable for a job. They explain to the woman that she is not being hired and the reason for this is due to her gender (See Appendix D). Another cartoon depicts a male who is incredulous that a female employee could feel she is experiencing gender inequality. Paradoxically, however, she does not even receive a chair to sit on (See Appendix E). This cartoon insinuates that gender influences work treatment, thereby exposing objectification. Moreover, critical media utilizes humour to make the modes of thought that contribute to gender inequality explicit. Morrison (2000), meanwhile, argues that higher education must advance democracy and social justice (p. 4). She asserts the importance of recognizing how people and knowledge are implicated with social beliefs in order to achieve this goal (Morrison, 2000, p. 3). To be sure, critical media supports ways of thinking that Morrison (2000) argues are imperative in the university (pp. 3-4). Control and Disciplining: Female Docility Popular media can also be seen to depict the last stages in the process of obligatory docility. This involves the control and disciplining of bodies (Rajagopal, Lecture 5, October 27th, 2009). The literature reveals that women face challenges in higher education (Morrison et al., POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 10 2005, p. 158; Mottarella et al., 2009, p. 230; Steele et al., 2002, p. 49). It was noted that these challenges be looked at as attempts to control female advancement that eventually leads to the disciplining of bodies (Morrison et al. 2005, p. 154), In The Proposal (2009) Margaret faces similar techniques of control and disciplining, as she has to sacrifice her relationships to be successful in her career. Following this, Margaret becomes disciplined by symbolically relenting to male social power. Typical of romantic comedies, Margaret and Andrew fall in love and Andrew moves to kiss Margaret. At this point a coworker exclaims Andrew is demonstrating he is “the boss” (The Proposal, 2009). While this comment is used to evoke laughter, it also implies that women must theoretically decide between being a “boss” or being in love. Further, the entire movie is premised on the fact that Andrew must agree to marry Margaret in order for her to keep her job (The Proposal, 2009). Therefore, while Margaret may be Andrew’s boss at work, Andrew retains the power and control in reality. Instances of control and disciplining are also displayed in Nurse Jackie (2009). The challenges that Jackie must face as a working mother are shown to the extreme. For one, she is unable to integrate her work and private life, maintaining an absolute separation between the two. In addition, her daughter suffers emotional breakdowns when Jackie goes to work (Daffodil, 2009; Nose Bleed, 2009; Pupil, 2009; School Nurse, 2009). This implies that Jackie cannot raise a healthy child while maintaining a career. In the end, Jackie becomes a disciplined body by turning to prescription pills to help her cope with her struggles. This addiction leads to intriguing story lines throughout the entire first season of the show (Nurse Jackie, 2009). Essentially, however, Jackie is artificially escaping from reality through her addiction, rather than challenging the normalization of working males and the disciplining of female bodies. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 11 Stern et al. (2005) show why such messages of obligatory docility are dangerous by revealing how media acts an apparatus of disciplinary power. They write of “parasocial attachment” where viewers of popular media feel they have an authentic bond with television characters (Stern et al., 2005, p. 223). Through “parasocial attachment” television characters impact individuals’ actions and values (Stern et al., 2005, p. 223). In this way, processes of obligatory docility in the media may have an effect on individuals’ actions. While popular media presents persuasive representations of obligatory female docility, critical media deconstructs such popular representations. For example, one cartoon utilizes humour to expose challenges that working mothers face (See Appendix F). Another comic makes one think about obligatory docility by depicting women in the business world having to use a male washroom (See Appendix G). Freedman (2003) advocates for critical teaching and learning whereby media representations can be discussed and analyzed (p. 94). Critical media encourages such practice as it deconstructs how female bodies become disciplined. One might suggest that popular media does not necessarily discipline females in masculine fields. For example, Long et al. (2001) note that ‘counter-stereotypes’ challenging the dominant depiction of scientists as male are being shown on television programs (p. 264). While these counter-stereotypes imply a critique of popular representations, they are still disseminated by the popular media. Bishop (2000) asserts that individuals must be cautious of media critiques generated by popular media, as they are only critical to the extent that the popular media allows (pp. 9-10). He argues that such criticism is produced with the goal of gaining profit (Bishop, 2000, p. 10). In effect, individuals’ incentives to be critical of the media are reduced, and the media’s control remains prominent (Bishop, 2000, p. 6). Counter-stereotypical shows are thus not resisting the disciplinary powers of popular media, but are rather supporting media control. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 12 This argument is illuminated in the song “Just a Girl” (See Appendix H). On the surface, the lyrics appear to be critiquing popular cultural depictions of women by mocking representations of females as fragile. In the end, however, this song is part of popular culture and only criticizes representations of female docility to the extent delineated by popular media (see Bishop, 2000, pp. 9-10). One lyric depicts a female’s desire to no longer be a girl because of her experiences of obligatory docility (Dumont & Stefanie, 1995). This presents the message that it is futile to challenge female docility, as the lyrics imply that her experiences will not change unless she is no longer a girl. This song is also dangerous since it initially appears critical of popular representations. As Bishop (2000) argues, such forms of media reduce one’s incentive to be critical (p. 6). Moreover, popular lyrics that appear critical on the surface actually support media control by encouraging a passive acceptance of media messages (see Bishop, 2000, p. 17). Concluding Thoughts In conclusion, the literature reveals that females in natural/physical sciences and graduate studies are turned into Foucault’s (1995) “docile bodies” through ‘disciplinary power.’ In analyzing popular media’s representations of ‘normalized’ female behaviour and obligatory docility it is clear that media is an apparatus of the disciplinary power. Although the media disseminates messages in public, in the words of Gerstl-Pepin (1998), these messages are too “thin” (as cited in Gerstl-Pepin, 2002, p. 39) as they are not easily open to scrutiny (Gerstl-Pepin, 2002, p. 39). Instead, obligatory female docility is portrayed in comedic, dramatic, and unsubvertable manners. At the same time, however, critical media reveals how females in masculine fields are inscribed by disciplinary powers. Unpacking and exposing the disciplinary power of popular media, one hopes, will serve to enhance the reflexive abilities of students and citizens, which would open the possibilities for resistance against gender inequality. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 13 APPENDIX A Critical Media: Normalization and Individuation (Sizemore. J. “Anyone else like to share a ‘glass ceiling horror story’?” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=jsin220>.) APPENDIX B Critical Media: Normalization and Individuation (Bacall, A. “No, this is not Mel’s secretary. This is Mel.” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=aba0459>) POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 14 APPENDIX C Objectification in Popular Media (Californication Advertisement. 1 Sept. 2009 <http://www.cityweekly.net/utah/imgs/media/Bill/Californication_Season_3.jpg>) APPENDIX D Critical Media: Surveillance and Objectification (Kes. “Of course it isn't a case of sexual discrimination. We just don't think you're the right man for the job.” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=ksmn955>.) POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 15 APPENDIX E Critical Media: Surveillance and Objectification (Flanagan, M. “Sex discrimination? What are you talking about?” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=mfl0325.>) APPENDIX F Critical Media: Controls (Streeter, B. “Sorry, still got my 'raising kids' head on...” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=bstn180>.) POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 16 APPENDIX G Critical Media: Disciplining (Jolley, R. "Do you ever worry that you've had to sacrifice your femininity to succeed?" Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=rjo0287>.) APPENDIX H Excerpt of Popular Media Song Lyrics: “Just a Girl” “…Cause I'm just a girl, little ol' me Don't let me out of your sight I'm just a girl, all pretty and petite So don't let me have any rights Oh. . . I've had it up to here! The moment that I step outside So many reasons for me to run and hide I can't do the little things I hold so dear 'Cause it's all those little things That I fear 'Cause I'm just a girl, I'd rather not be…” (Dumont, T. & Stefani G. (1995). Just a Girl [No Doubt]. On Tragic Kingdom [CD]. Interscope Records. Lyrics accessed online: http://www.lyrics007.com/No%20Doubt%20Lyrics/Just%20A%20Girl%20Lyrics.htm) POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 17 References Aubrey, J.S. (2006). Effects of Sexually Objectifying Media on Self-Objectification and Body Surveillance in Undergraduates: Results of a 2-Year Panel Study. Journal of Communication, 56(2), 366-386. Austin, T.K. (Writer), & & Buscemi, S. (Director). (2009). Daffodil [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem,, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc. Bacall, A. “No, this is not Mel’s secretary. This is Mel.” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=aba0459> Barata, P., Hunjan, S., & Leggatt, J. (2005). Ivory Tower? Feminist women’s experiences of graduate school. Women’s Studies International Forum, 28(2/3), 232-246. Bernauer, J.W., & Mahon, M. (1994). The Ethics of Michel Foucault. In G. Gutting (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Foucault (pp. 141-158). New York: Cambridge University Press. Bishop, R. (2000). Good Afternoon, Good Evening, and Good Night: The Truman Show as Media Criticism. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 24(1), 6-18. Blackhurst, A.E., & Auger, R.W. (2008). Precursors to the gender gap in college enrollment: children’s aspirations and expectations for their futures. Professional School Counseling, 11(3), 149-158. Bradley, K. (2000). The incorporation of women into higher education: Paradoxical outcomes? Sociology of Education, 73(1), 1-18. Californication Advertisement. 1 Sept. 2009. <http://www.cityweekly.net/utah/imgs/media/Bill/Californication_Season_3.jpg> Cho, D. (2007). The role of high school performance in explaining women’s rising college enrollment. Economics of Education Review, 26(4), 450-462. Dumont, T. & Stefani G. (1995). Just a Girl [No Doubt]. On Tragic Kingdom [CD]. Interscope Records. Lyrics accessed online: <http://www.lyrics007.com/No%20Doubt%20Lyrics/Just%20A%20Girl%20Lyrics.htm> Eschholz, S., Bufkin, J., & Long, J. (2002). Symbolic Reality Bites: Women and Racial/ethnic Minorities in Modern Film. Sociological Spectrum, 22, 299-334. Flahive, L. (Writer) & Buscemi, S. (Director). (2009). Pupil [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem,, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA Flanagan, M. “Sex discrimination? What are you talking www.cartoonstock.com <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=mfl0325.> 18 about?” Cartoon. Foucault, M. (1984a). Complete and Austere Institutions. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault Reader (pp. 214-225). New York: Pantheon Books. Foucault, M. (1984b). Docile Bodies. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault Reader (pp. 179-187). New York: Pantheon Books. Foucault, M. (1984c). The Means of Correct Training. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault Reader (pp. 188-205). New York: Pantheon Books. Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and Punish (A. Sheridan, Trans.) (2nd ed.) Studies in Critical Theory. New York: Vintage Books (Original work published 1978). Freedman, D. (2003). Acceptance and Alignment, Misconception, and Inexperience: Preservice Teachers, Representations of Students, and Media Culture. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 3(1), 79-95. Gerstl-Pepin, C.I. (1998). Cultivating democratic educational reform: A critical examination of the A+ schools program. Upublished doctoral dissertation, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Gerstl-Pepin, C.I. (2002). Media (Mis)Representations of Education in the 2000 Presidential Election. Educational Policy, 16(1), 37-55. Giroux, H. A. (2002). The Corporate War against Higher Education, Workplace: A Journal for Academic labour, 5. 1 http://www.louisville.edu/journal/workplace/issue5p1/giroux.html accessed 12 July 2006. Hart, J. (2006). Women and Feminism in Higher Education Scholarship: An Analysis of Three Core Journals. Journal of Higher Education, 77(1), 40-61. Herring, S.C., & Marken, J.A. (2008). Implications of Gender Consciousness for Students in Information Technology. Women’s Studies, 37(3), 229-256. Herzig, A.H. (2004). ‘Slaughtering this beautiful math’: graduate women choosing and leaving mathematics. Gender and Education, 16(3), 379-395. Jolley, R. "Do you ever worry that you've had to sacrifice your femininity to succeed?" Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=rjo0287>. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 19 Kes. “Of course it isn't a case of sexual discrimination. We just don't think you're the right man for the job.” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=ksmn955>. Kurtzman, A., Orci, R., McLaglen, M., & Bullock, S. (Executive Producers), & Fletcher, A. (Director). (2009). The Proposal [Motion Picture]. United States: Touchstone Pictures. Lauzen, M.M., & Dozier, D.M. (2005). Maintaining the Double Standard: Portrayals of Age and Gender in Popular Films, Sex Roles, 52(7/8), 437-446. Leone, R., Peek, W.C., & Bissell K.L. (2006). Reality Television and Third-Person Perception. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 50(2), 253-269. Long, M., Boiarsky, G., & Thayer, G. (2001). Gender and racial counter-stereotypes in science education television: a content analysis. Public Understanding of Science, 10, 255-269 McKinley, E. (2005). Brown Bodies, White Coats: Postcolonialism, Maori women, and science. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 26(2), 481-496. Middleton, S. (2005). Pedagogy and Post-coloniality: Teaching “Education” Online Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 26(4), 511-525. Morrison, T. (2000). How Can Values Be Taught in http://www.umich.edu/~mqr/morrison.htm accessed 10 May 2006 the University? Morrison, Z., Bourke, M., & Kelly, C. (2005). ‘Stop making it such a big issue’: Perceptions and experiences of gender inequality by undergraduates at a British University. Women’s Studies International Forum, 28(2/3), 150-162. Mottarella, K.E., Fritzsche, B.A., Whitten, S.N., & Bedsole, D. (2009). Exploration of “Good Mother” Stereotypes in the College Environment. Sex Roles, 60(3/4), 223- 231. Oswald, D.L. (2008). Gender Stereotypes and Women’s Reports of Liking and Ability in Traditionally Masculine and Feminine Occupations. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(2), 196-203. Rajagopal, I. (2009). Lecture 5, October http://www.yorku.ca/rajagopa/sosc3930.htm/ 27th: Body. Retrieved from: Shepherd, J. H. (Writer) & Feig, P. (Director). (2009). Nose Bleed [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem,, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc. Sizemore. J. “Anyone else like to share a ‘glass ceiling horror story’?” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=jsin220>. POPULAR VS. CRITICAL MEDIA 20 Steele, J., James, J.B., & Barnett, R.C. (2002). Learning in a Man’s World: Examining the Perceptions of Undergraduate Women in Male-Dominated Academic Areas. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(1), 46-50. Stern, B.B., Russel, C.A., & Russel, D. W. (2005). Vulnerable Women on Screen and at Home: Soap Opera Consumption. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 222-225. Stern, S.R. (2005). Self Absorbed, Dangerous, and Disengaged: What Popular Films Tell Us About Teenagers. Mass Communication & Society, 8(1), 23-38. Streeter, B. “Sorry, still got my 'raising kids' head on...” Cartoon. www.cartoonstock.com. <http://www.cartoonstock.com/cartoonview.asp?catref=bstn180>. Wall, S. (2008). Of heads and hearts: Women in graduate education at a Canadian University. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31(3), 219-228. Wallem, L., Brixius, L., Melfi, J., & Manabach, C. (Executive Producers). (2009). Nurse Jackie [Television Series). New York: Showtime Networks Inc. Wallem, L. Dunsky, E., & Brixius, L. (Writers), & Coulter, A. (Director). (2009). Pilot [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem,, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc. Shepherd, J. H. (Writer) & Feig, P. (Director). (2009). Nose Bleed [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem,, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc. Zander, C. (Writer), & Buscemi, S. (Director). (2009). School Nurse [Television series episode]. In L. Wallem, L. Brixius, J. Melfi, & C. Manabach (Producers), Nurse Jackie. New York: Showtime Networks Inc.