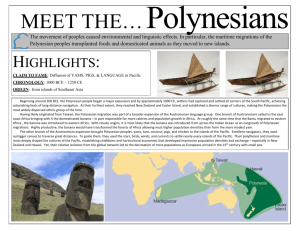

Identification of national processes that may threaten the

advertisement