Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability

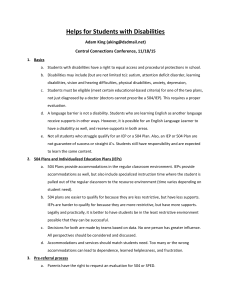

advertisement