StdsComment-web09

advertisement

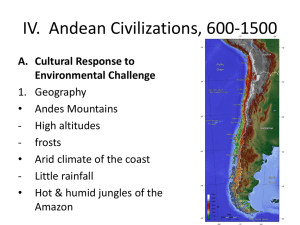

2008 Field School - Students’ Reflections Andean Culture and Society The Andean people have maintained a strong sense of kinship and community relations. Community values are what have allowed Andean culture and society to survive for thousands of years; Andean spirituality and respect for their surroundings and one another has touched me in so many ways. Through the vast biodiversity found here, people have developed a symbiotic relationship and understanding with their surroundings, and are capable of maintaining a self sustainable lifestyle without completely destroying the sheer beauty existing here. Despite structural limitations, I don’t see a lack of vibrance in Andean culture. People work together to ensure that their needs are met. They have vast social networks that they call upon for fiestas. They organize themselves to ensure that women give birth in a healthy manner. Educators and parents cooperate to guarantee decent education. I have seen community organization in the Andes that puts the US to shame, all without any form of coercion, neither economic nor physical. The words for health and body do not exist in Quechua language - their genuine notions of interconnectedness are expressed in relational terms, so that their ails are inseparable from those of their neighbors. I felt welcomed as an outsider even when intentions were unkown and was allowed to walk among the people without prejudice. I have felt a strong acceptance from the small communities we have visited; it saddened me to leave. The generosity has far exceeded my expectations. The Andean cultural concept of Patsa Mama (Mother Earth) is something that encompasses all aspects of my learning experience here. The strong link Andean people have with the land is evident in the way they sow and reap, the way they speak, and the way they relate to the four parts of their cosmovision. The ways in which people interact with the natural world demonstrate a deep respect and responsibility to Patsa Mama that is more reciprocal than the relationship many people I know have with the earth. In the context of fiesta, offerings are made to Patsa Mama, a gesture that to me strengthens, or rather, maintains the connection between us and the natural. The conscious presence and influence of mountains pervade every facet of life here, from the source of water to food variety and cultivation, to the myths and folklore. The lunar phases appear in Andean perceptions of agricultural cycles – with time represented in a circular counterclockwise direction, rising and setting east to west. In Andean culture, the trees, mountains, sun, moon, water…are all like family members, things to be adored, which you raise and which raise you at the same time. The thing that impresses upon me the most in Andean life, that seems to bind each arena I’ve been accustomed to perceiving as separate, is the forward and backward simultaneous thinking, the temporal connectivity of the present. We have seen this play of time enacted and lived in fundamental parts of life from growing and planning to community networks of support and obligation, from the tangible to the social. I’ve learned that unearthing potatoes for the present, for food in this season, is a reward for hard work the season before, and for the foresight of selecting a successful assortment of seedlings to save for planting. Each potato brought to light is a gift of the ancient practices of seed selection, and as such, Andean heritage is stored in selection relationships and practices as well. I was impressed repeatedly during this program at the trade and gift, or obligation relations that serve to tightly integrate one family with another, spreading out a resilient, enduring and self-perpetuating support network to prevent total loss in times of stress. As with potatoes, the fiesta is of core importance to the integrity and maintenance of concepts of community. The enactment of the fiesta calls upon and reinforces social bonds by which the community persists and by which it understands itself as a community, but likewise the enactment plants the seeds and lays the groundwork for reinforcing these social and community identities in years to come. Andean music played for spirits ranges from the spirits of the mountain to the moon, music for the heart is extended to the hearts of animals and plants. One does not just “play” music – one becomes the music and unites with spirits and nature, and also reaches the various dimensions of being in Andean cosmovision, which together create a sense of holism that binds communities with the earth. Although it has been only a short period of time with Quechua classes, I feel that I have learned a lot. Even more, learning Quechua has allowed me to gain a better understanding of Andean culture. It has been exciting for me to open my mind to new ways of understanding the world. The Andean way of life is under constant threat of modernization, economic struggle, health problems, and the consequences of the current global warming crisis. If the glaciers continue to melt, the Andean world will forever change. Field Work I have learned not to be afraid to jump in, get my hands dirty, ask questions, learn from doing – no matter how hard it might be; experience the learning, learn the experience! After participating in the cosecha de maíz, I realized that Anthropology cannot be taught in a classroom. Diving in head first is the only way to go. As we helped harvest, we joked around, told stories, asked questions and answered some, too. This interaction, the process of building a relationship in the middle of a cornfield, is key. There are many ways to take action, but first one must be open and committed to participate. This is what I’ve learned about doing fieldwork. Overall, it was made very clear that unless a community is involved actively and fully in a project and its implementation, the residents will not feel the drive, enthusiasm and personal responsibility for changing anything. Perception of need creates willingness, and doing fieldwork is an important part of finding out whether that perception exists, how strongly it is felt, and far it can be taken to institute community-driven change. Field work has influenced my personal philosophy which is now of community advocacy; this means helping people help themselves. I have learned that it is important to spend time talking with people and paying attention to their communication – verbal and nonverbal, regardless of where fieldwork is done. Being in a group and working as a team to generate questions and learn about this community was a new experience for me. I learned how to work as a team by bringing out and encouraging other team members to do what they are good at, and giving them other input. Acting as a mirror and reflection for others and learning how to listen to team members express themselves was beneficial. We worked well as a team. There seemed to be a perfect distribution of interests and determination to carry out activities and get something out of this research. This was clearly demonstrated in our variety of topics connecting our final presentations. Experience seems to be the most concrete way of learning for me. The field work experience in itself became its own sort of field work! After this experience I feel much better prepared for future fieldwork. I have lots of ideas, methods, and more flexible approaches to bring to new field opportunities. I have learned that the Experiential Learning Cycle does hold true – that reflecting, analyzing, generalizing, and then modifying your experiences really does seem like the best way to make progress in the field. Relying, to begin with, upon first impressions and flushing them out later with the impressions of others, both insiders and outsiders, hearing about what they saw, what stood out, what they thought, is an important field research process. Another significant part of field training was navigation and adaptation; finding ourselves in unfamiliar places, with foreign modes of transport, sustenance and communication, made us take careful note of geographic surroundings, make maps and drawings to guide us. Perhaps most importantly, we learned to be part of our surroundings. This element of fieldwork is the basis for participating, delving into the gift networks as much as the dances, joking and sharing food, and drinking chicha from the communal cup. I was looking for a model of action and purpose in Anthropology, and I believe the Community Action Cycle provides a foundation of this, and also an opportunity for me to be able to retain the ideas, ideals, methods and goals from my current profession of Education. Alternative Energy Systems It was especially inspiring to see that Pocha, a self-taught individual without an engineering degree or similar technical background is able to put these methods into action, and made these concepts come alive for me. I am constantly amazed at the efficiency of the farm. Pocha’s explanations are easy to comprehend, and as we continue to explore the farm we understand more how it all works. I admire the dedication to renewable energy on the farm, such as the solar stoves, ovens, hot water system, electricity, sewage, as well as the use of organic food waste – the compost, animals devouring peels, and scraps, etc. By far my favorite ecological aspect of the farm is the waste pond. Someone once told me that there is beauty in shit. I never really believed them until the other day when you showed us the calla lilies. To be here is an inspiring experience. The hard work and intuitive design of the farm is amazing. Sustainable design, alternative energy, organic farming and integration with nature are worth learning about. It’s great to see an actual working example of someone making a minimal impact on the environment. Pocha’s explanations of how she heats the water and purifies our waste is inspiring. The fact that the ranch is basically self-sustainable with little negative impact to the surrounding environment is a rare thing. The ranch serves as a model to community members to show that alternative energy can be used and is the best way to diminish pollution. I have definitely learned more about energy and resource conservation here on the ranch. I never was so explicitly taught reasons to conserve, and it inspired my faith that each and every person can, in fact, make a difference by changing our behaviors in our environment and community. The Setting I could not desire a more peaceful setting to learn in. I like the fact that Pocha’s ranch is within the community of Cajamarquilla so students have the opportunity to interact with community members. The “remote” setting forced us to interact with the local community early on. I appreciated the fact that it was a bit of a hike to get to town, getting to pass the people on the path, and observe goings-on en route to town was an integral part of the experience. This setting serves as a metaphor for a sense of sharing and reciprocity; from the pre-fiesta lunch given for those who choose to contribute, to the sharing of a single cup among a group of people drinking chicha, one gets a sense of the importance of closeness and community participation in Andean society. The ranch framed my perceptions of the surroundings and provided a context for what I saw as areas to improve environmentally. Many opportunities for immersion experiences were presented, but never was it overwhelming. An excellent balance. I loved being in a beautiful mountain valley and seeing glaciers (though this made me sad - they are disappearing). The very natural setting brings people close together. Being so far out of one’s element yet in such a peaceful one, facilitates learning and, moreover, personal growth. At night, to be on the mountain in darkness and silence (aside from the occasional fireworks) was ideal for contemplation.