Serology Write-Up

advertisement

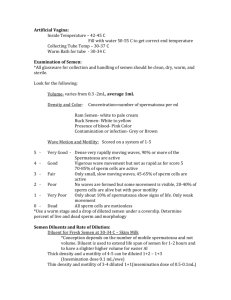

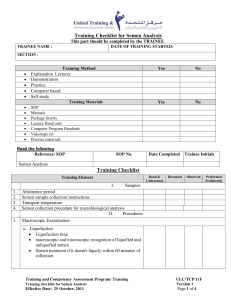

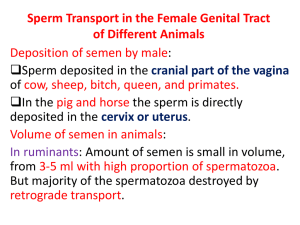

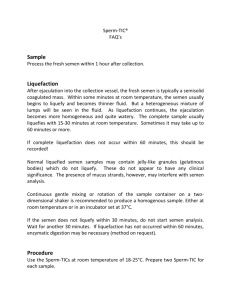

Serology Serology is the study of the properties and effects of body-fluid evidence. Most commonly, serological evidence involves analysis of blood, semen or saliva. Less frequently seen are cases involving urine, perspiration or fecal matter. Serological analysis can serve two main purposes in a criminal case. First, and its primary use, is to identify a stain for the presence of bodily fluids. Second, is the use of genetic markers in the fluids to associate the evidence sample with a particular group of people. This later purpose is much less frequently used in modern criminal investigations because the discriminatory power of DNA testing is much greater than that of serological analysis. We discuss here the three main types of serological evidence: blood, semen, and saliva. Consult with the sources listed at the end of this article if your case involves other types of bodily fluid. Blood Blood evidence is associated with a wide spectrum of crimes, from simple assaults to homicides. Usually in the more serious cases, forensic serologists will conduct examinations of suspected blood evidence in order to (1) identify the material as blood and (2) associate it with particular individuals as possible sources. Identification of Blood The first question a serological blood analysis will ask is: “Is this stain blood?” To answer that question, forensic labs use two types of tests: presumptive tests and confirmatory tests. Each type of test detects for the presence of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells. (Hemoglobin is red, and it is what gives blood its reddish appearance.) Presumptive tests are extremely sensitive, thus requiring very little sample to make a presumptive blood determination. The tests are useful as a searching device, to locate spots and stains that might not be obvious to the naked eye. The limitation on presumptive tests, however, is that materials other than hemoglobin can cause a positive reaction. For example, certain plant enzymes can cause a false positive reaction. Because of the prospect of false positives, according to one treatise (albeit a dated one), “[m]ost authorities agree that positive presumptive tests alone should not be taken to mean that blood is definitely present.” Peter R. De Forest, et al., Forensic Science: An Introduction to Criminalistics, at 248 (1st ed. 1983) (emphasis in original). There are many different types of presumptive tests. One type of presumptive test that bears mentioning is luminol. At crime scenes, luminol is powerful way in detecting blood in darkness or blood that has been substantially diluted. Luminol reacts with hemoglobin in the blood to produce a visible, bluish-green glow (like a light stick) that reveals the bloodstain. Luminol is particularly useful at crimes scenes that have been altered or “cleaned” by the suspect. Confirmatory tests, on the other hand, are less sensitive than presumptive tests and, therefore, require more material. As a result, for small samples, forensic labs often will only conduct a presumptive test for blood, especially if the sample needs to be preserved to conduct DNA testing. Like presumptive tests, confirmatory tests detect the presence of hemoglobin. A positive confirmatory test is virtually certain evidence that blood is present. Finally, in some cases, after a stain is identified as blood it may be necessary to confirm that it is human blood, as opposed to animal blood. Determining the species of origin of the blood specimen is done using an immunological test known as a precipitin test. Individualization of Blood Specimen Once a specimen is known to be human blood, the specimen can be used discriminate among groups of people. Blood contains many inherited factors. Because many of these factors are independent of one another, there exist different combinations of factors in different people. Determining what factors are present in a blood specimen is known as blood grouping. An example of blood grouping is the familiar ABO blood-group system. There are four major ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. Types A and O are the most common in the human population, with AB the most rare. Other blood-group systems include the Rh system, the MNSs system, the Kell system, and the Duffy system. Differences among these systems allows for discrimination among people. In modern forensics, however, blood grouping is rarely used as a discriminatory instrument, because DNA testing is far more powerful means of differentiating among people. Semen Semen, or seminal fluid, is the fluid produced by the male reproductive organs. Normally, semen contains spermatozoa and secretions from the seminal vesicles, the prostate gland, and the bulbourethral gland. Spermatozoa are very small cells consisting of a head, mid-piece, and tail. These cells can be detected under a microscope. A suspected seminal stain cannot, however, be viewed directly for spermatozoa. Lab techniques designed to isolate and to extract spermatozoa must first be performed before looking under the microscope. The finding of sperm cells under a microscope constitutes proof of the presence of semen. The absence of spermatozoa does not, however, mean the absence of semen. Seminal fluid can be detected using other identification techniques. One of the more powerful tests is known as the “p30 test,” which detects for a specific antigen produced by the prostate gland. There are a number of reasons why seminal fluid may not contain spermatozoa. Some men naturally have low sperm counts. Other men may have no spermatozoa because they have been vasectomized. In other cases, the absence of spermatozoa may have nothing to do with sperm-count of its depositor. Spermatozoa are fragile and begin to degenerate within hours of ejaculation. The older a semen stain, especially one exposed to the elements, the less likely it is that spermatozoa will be present. Likewise, spermatozoa in living and deceased persons will degrade over time. For information concerning the degradation rate of spermatozoa, a good start is the study by Drs. Kim A. Collins and Allan T. Bennett, Persistence of Spermatozoa and Prostatic Acid Phosphatase in Specimens from Deceased Individuals During Varied Postmortem Intervals, The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 22(3):228-232 (2001). Saliva Saliva detection usually is based upon the presence of an enzyme known as amylase. That enzyme is secreted from three pairs of salivary glands. Amylase is a very stable enzyme and can be detected even on dried articles. With the exception of feces, no other body fluid approaches the level of amylase activity in dried stains. Thus, a high level of amylase is strongly associated with the presence of saliva. Bibliography: Peter R. De Forest, et al., Forensic Science: An Introduction to Criminalistics, Chapters 9 (Blood) and 10 (Bodily Fluids), McGraw Hill, New York (1983). R.E. Gaensslen, Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology and Biochemistry, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. (1983). R.E. Gaensslen and F.R. Camp, “Forensic Serology,” in C.H. Wecht (ed.) Forensic Sciences, vol. 2, chap. 29, Matthew Bender, New York (1981). Drs. Kim A. Collins and Allan T. Bennett, Persistence of Spermatozoa and Prostatic Acid Phosphatase in Specimens from Deceased Individuals During Varied Postmortem Intervals, The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 22(3):228-232 (2001)