evolutionary - CLSU Open University

advertisement

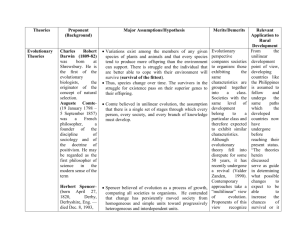

APPENDIX C, Course Reference No. 3 Evolutionary Perspectives Evolutionism is the belief that every society progresses from simple beginnings through stages of ever-increasing complexity (Spencer and Inkeles, 1982). Early social scientists, particularly sociologists like Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Karl Marx, Edward Taylor, and others were influenced in their theorizing about society by the ideas of evolution as espoused by Charles Darwin. Some held that society underwent a progressive development or unilinear evolution toward progress. Others like Comte held a pluralistic view. The main thesis in evolutionary theories is that human societies developed from the simple or primitive condition to more complex or civilized forms and passed through certain stages in the process. Models in the study of modernity go back to the evolutionism of Spencer and Durkheim concerning the process of change in terms of increasing social differentiation and complexity. Charles Darwin. The pioneering work of Charles Darwin in biological evolution significantly influenced the 19th century theories of social change. Darwin believed that variations exist among the members of any given species of plants and animals and that every species tend to produce more offspring than the environment can support. There is struggle and the individuals that are better able to cope with their environment will survive (survival of the fittest). Thus, species change over time. The survivors in the struggle for existence pass on their superior genes to their offspring. Auguste Comte. He tried to identify the various stages through which all societies must progress. Comte believed in unilinear evolution, the assumption that there is a single set of stages through which every person, every society, and every branch of knowledge must develop. He suggested that not only society but individuals and sciences pass through three stages: theological stage where people think inanimate objects are alive; metaphysical stage where events are explained in terms of abstracts forces, and; positive stage where the people explain events in terms of natural processes. He believed that societies all must progress through the same set of historical stages. Although his law of three stages (theological or fictitious, metaphysical or abstract, and scientific or positive) soon ceased to be convincing, his approach to sociology greatly influenced later theorists. Comte did little research, so that his significant contribution is having inspired other scholars to advance sociology. Herbert Spencer. He also believed of evolution as a process of growth, comparing all societies to organisms. He contended that change has persistently moved society from homogeneous and simple units toward progressively heterogeneous and interdependent units. He used the concept of evolution of animals to explain how societies change over time and adapted Darwin’s evolutionary view of the “survival of the fittest”, an approach termed Social Darwinism. He argued that it is “natural” that some people are rich while others are poor. He viewed that if unimpeded by outside intervention, those individuals and social institutions that are “fit” will survive and proliferate while those that are “unfit” will in time die out. Lewis Henry Morgan. An early American anthropologist, also saw societies as evolving through a number of stages. His principal attention was focused on technological factors, kinship systems, and property relations to social and political institutions. He concluded that societies could be ordered along an evolutionary continuum through which human must pass everywhere. He argued that the experience of people has run in nearly uniform channels. Human necessities under similar conditions have been essentially the same, and the operation of human mentality is uniform throughout the various human societies. He described the progress of humankind through three main stages of evolution: savagery, barbarism and civilization. The stages of savagery and barbarism were further subdivided into lower, middle, and upper, such that the entire scheme had altogether seven graduation of evolution. They are as follows: 1. Lower status of savagery, from the infancy of the human Race to the commencement of the next period. 2. Middle status of Savagery, from the acquisition of fish subsistence and a knowledge of the use of fire, to etc. 3. Upper Status of Savagery, from the invention of the Bow and Arrow to etc. 4. Lower Status of Barbarism, from the invention of the art of Pottery, to etc. 5. Middle Status of Barbarism, from the domestication of animals on the eastern hemisphere, and in the western from the cultivation of maize and plants by irrigation, with the use of adobe bricks and stone, to etc. 6. Upper Status of Barbarism, from the invention of the process of smelting Iron Ore, with the use of iron tools, to etc. 7. Status of Civilization, from the invention of a Phonetic Alphabet with the use of writing, to the present time. Each stage and substage were assumed to have been initiated by a major technological invention. Thus, the second stage of savagery was brought into being by the art of making fire and catching fish, and the third by the bow and arrow. Barbarism began with the invention of pottery making. Its second stage was characterized by the domestication of animals, and its third by the technology of melting iron. Civilization was heralded by the invention of the phonetic alphabet. Each of these stages of technological evolution, according to Morgan, was correlated with characteristic developments in religion, the family, political organization and property arrangements. Morgan’s famous book Ancient Society, in which his ideas of evolution were stated, made a strong impression on Marx and his co-worker, Engels. The latter, following the advice of Marx, in 1884 published The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State, a volume making extensive use of Morgan’s theories and of his illustrations, taken largely from observations of American Indian societies. William Graham Summer (1840-1910). One of the most important American sociologists, became an outspoken theorist of social evolution. In a famous dictum, Summer argued that stateways could not change folkways. That is, social improvement could only come about through natural evolution of society and not by legislation. His arguments are still echoed today by those who oppose laws providing for more equitable treatment of minorities on the ground that morality cannot be legislated. Lester Frank Ward (1841-1913). He believed that both human beings and human society had developed through eons of evolution, but he maintained that once intellect has evolved in humans, they gained the ability to help shape the subsequent evolution of social forms. Through the application of intelligence, people could effect desired changes in society. In this respect, Ward was following in the tradition of Auguste Comte, who maintained that human intelligence had reached the point where society could be reconstructed through application of the scientific method. Ferdinand Toennies. He perceived two periods in the history of the great systems of culture: a period of Gemeinshaft (rural and folklife) and Gesellshaft (cosmopolitan, rational urban life). Gemeinshaft refers to social life that is characterized by personal, informal considerations, with tradition and custom prevailing. This kind of life is common in small agricultural communities and rural areas prior to industrialization. The groups in which people spent much of their time is called primary groups: small groups involving personal, intimate, and non specialized relationships. Gesellshaft is a social life characterized by specialization, individualism, impersonality and rationality. Specialization is seen in the form of separate social roles and social institutions designed to accomplish specific tasks and goals. Social ties took on a “contractual” nature in which calculation, impersonality, and formality prevail. More time is spent on secondary group: groups in which people have few emotional bonds, ties are impersonal, and people are seeking to achieve specific, practical goods. Howard P. Becker (1899-1960). Saw the transition as being from a sacred, traditionally oriented society to a secular society that evaluates customs and practices in terms of their pragmatic outcomes (1950). Robert Redfield (1897-1958). He put the transition as being from folk to urban (folk-urban continuum). He described folk society as small, isolated and homogenous with a strong sense of group solidarity. The ways of living are conventionalized into that coherent system which we call a “culture”. Behavior is traditional, spontaneous, uncritical and personal. There is no legislation or habit of experiment and reflection for intellectual ends. Kinship, its relationships and institutions are the type categories of experience and the familial group is the unit of action, the sacred prevails over the secular, the economy is one of status rather than of market. Change for Radfield is the consequence of an “increase of contacts bringing about heterogeneity and disorganization of culture.” By the early part of the twentieth century, enough information had been gathered by social scientists on societies throughout the world to make it appear unlikely that societies everywhere had passed through the same series of stages. Thus the idea of unilinear evolution was generally discarded. Furthermore, both the general idea that present societies represent the highest stage in any evolutionary sequence and that there is a necessary link between social change and progress were discredited. The evolutionary approach is, however, still with us in more contemporary forms. Gerard and Jean Lenski. They maintain that continuity, innovation, and extinction are basic aspects of the evolutionary process and “evolution is essentially cumulative change: it involves the gradual addition of new elements to a continuing base. The idea of a unilinear evolution – that is, all societies inevitably passing through the same set of fixed stages – has given way to the idea of a “multilinear” evolution. Those who hold this view reason that since societies were often very different to begin with, they may have appropriately undergone varying patterns of change and that the same patterns of change may produce slightly varying products in society that started from different beginnings. Rostow (1961). As a result of his dissatisfaction with Karl Marx’s explanation of the evolution of society and the cause of change therein, W.W Rostow tried to provide an alternative answer that elaborates on the relation of economic to social and political forces in the development of societies. According to him, growth and development to economic maturity proceed through the following stages: Five stages of economic development: 1. Traditional Setting Society. It is one through which structure is developed within limited production functions based on pre-Newtonian science and technology and on pre-Newtonian attitudes towards the physical world. Such a society is characterized by a limited level of productivity, pre-occupation with agriculture, a social structure with slow or no mobility and a value system that evolves on fatalism. The dynasties in China, the civilizations of the Middle East and the Mediterranean, and the world of Medieval Europe are typical examples. 2. The Preconditions for “Take-off”. This is the transitional era when society prepares itself or is prepared by external forces for sustained growth. Initially, a society is predominantly agricultural; social life is built around a relatively small self-sufficient region; birth rates are high as a response to hard life; and income is relatively above minimum levels of consumption but concentrated in the hands of the landowners. In the transition process, all of these must change towards a shifting of manpower to industry or manufacturing; the orientation of life to a larger social setting; and decline of births and transfer of monetary resources for improvement of basic services. Economically, the significant changes are development of extractive industries, increase in agricultural production, and build up of social overhead capital as part of increases in total investments. Socially or politically, a new and more aggressive leadership arises as a strong sense of nationalism develops. 3. The Take-off. This pertains to that decisive interval in the history of a society when growth becomes its normal condition. It is characterized by these interrelated conditions: a rise in the rate of productive investment; the development of one or more substantial manufacturing sectors with a high rate of growth; and the existence of quick emergence of political, social, and institutional frameworks which exploit the impulses to expansion in the modern sector and the potential external economy effects of the take-off and which give growth an ongoing character. 4. The Drive toward Maturity. This is the period when society has effectively applied the range of modern technology to the bulk of its resources. It is where the leading sectors of the take-off stage are being supplanted by new ones and therefore the industrial process becomes differentiated. The drive to maturity leads to changes in the composition, real wage, outlooks, and skills of the working force; a character of the leadership and in the little boredom of society with the miracle of industrialization. Countries that have reached technological maturity are Great Britain (1850), United States (1900), Germany (1910), France (1910), Sweden (1930), Japan (1940), Russia (1950), and Canada (1950). 5. The Age of High Mass Consumption. This represents the period wherein men begin to take for granted what they are born to, in this case, a well-advanced industrial society. Their minds turn increasingly to reconsider the ends to which the mature economy may be put. Here, is a shift of attention from supply to demand. From problems of production to problems of consumption and of welfare in the widest sense. In this post-maturity stage, three directions may be pursued: a. The national pursuit of external power and influence, that is, the allocation of increased resources to military and foreign policy. b. The use of resources of a mature economy in the attainment of a welfare state. c. The expansion of mass consumption levels into the range of durable consumers’ goods and services. The United States is the first of the world’s societies to move sharply from maturity into the age of high mass consumption, but in no sense hasn’t fully achieved the move. This age is still gathering momentum in most of the countries of Eastern Europe and other growing economies of the world. Rostow differs with Marx essentially in this respect. Though Rostow’s theory is an economic way of looking at whole societies, he does not consider political, social, and cultural systems as mere superstructures of the economy. To him, societies are interacting organisms. While economic change has political and social consequences, it can also be a consequence of the changes in the two. As a matter of fact, many of the profound economic changes were brought about by non-economic human motives and aspirations. A glaring conclusion of Rostow’s work is the importance of technology and capital in the growth of the economy. This became the basis of the claim that underdeveloped countries, lacking both advanced technology and capital investments have to depend on mature economies to spur their material growth. Smith (1973) identified the following general characteristics of evolutionary theories: 1. Holism – studying the whole unit rather than its parts 2. Universalism – change is natural, universal, perpetual and ubiquitous, and requires no explanation 3. Potentiality – change is inherent and endogenous in the unit undergoing change. 4. Directionality – change is progressive. 5. Determinism – change is inevitable and irreversible for all units. 6. Gradualism – change is continuous, cumulative growth. 7. Reductionism – “laws of succession” are uniform and the basic topic of change is everywhere the same. Unit of Analysis: The evolutionary theories take society as the unit of analysis of social change. Criticisms: One criticism of unilinear evolution is the fact that not all societies have to go through the same stages. Some are able to skip stages through diffusion, the spread of cultural trait from one society to another. Summary: Evolutionary perspectives compare societies to organisms: those exhibiting the same characteristics are grouped together into a class. Societies with the same level of development belong to a particular class and are therefore expected to exhibit similar characteristics. From the unilinear development point of view, developing countries, like the Philippines, is assumed to follow and undergo the same paths which the developed countries now have undergone before reaching their present status. The theories herein discussed serve as guide in determining what possible changes to expect to be able to increase the chances of survival or it gives direction on what coping mechanism to adopt to enhance future success. The evolutionary perspective holds the belief that every society progresses from simple beginnings through stages of increasing complexity. The unilinear evolution assumes that there is a single set of stages through which every society must develop. Auguste Comte is credited as being the founder of sociology. He emphasized that the study of society must be scientific, and urged sociologist to employ systematic observation, experimentation, and comparative historical analysis. He also divided the study of society into social statics and social dynamics. Herbert Spencer viewed society as a system, a whole made up of interrelated parts. He also set forth an evolutionary theory of historical development, one that depicted the world as growing progressively better. Although evolutionary theory fell into disrepute for some fifty years, it has recently undergone a revival (Vander Zanden, 1990). Contemporary approaches take a “multilinear” view of evolution. Proponents of this view recognize that “change” does not necessarily imply “progress”. That change occurs in different ways, and that change proceeds in many different directions. References a. Etzioni and Etzioni.Social change, sources, patterns and consequences. Basic Books, Inc. USA. b. Lauer, R. H. 1982. Perspectives on social change. Allyn and Bacon Inc.USA. c. Muhi, E. T., Panopio, I.S., and Salcedo L. L. 1993. Dynamics of development in the Philippine perspective. pp. 17-49. d. Puzon, Rowena. 2006. Compilation of theories. A requirement of RD 704 course under Dr. Fe L. Porciuncula. e. Rivera, Fermina Talens. 2003. Compilation of theories and strategies of social change. f. Rostow, Walt T. 1961. The stages of economic growth: A non-Communist manifesto. New York: Cambridge. g. So, Alvin, 1997.Social change and development. Sage Publications. h. Smelser, N.J. 1994. Sociological theories. International Social Science Journal, USA. i. Vago, Stevens.1980. Social change. Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, New York. j. Several readings from the INTERNET