Ultrasound of the liver

advertisement

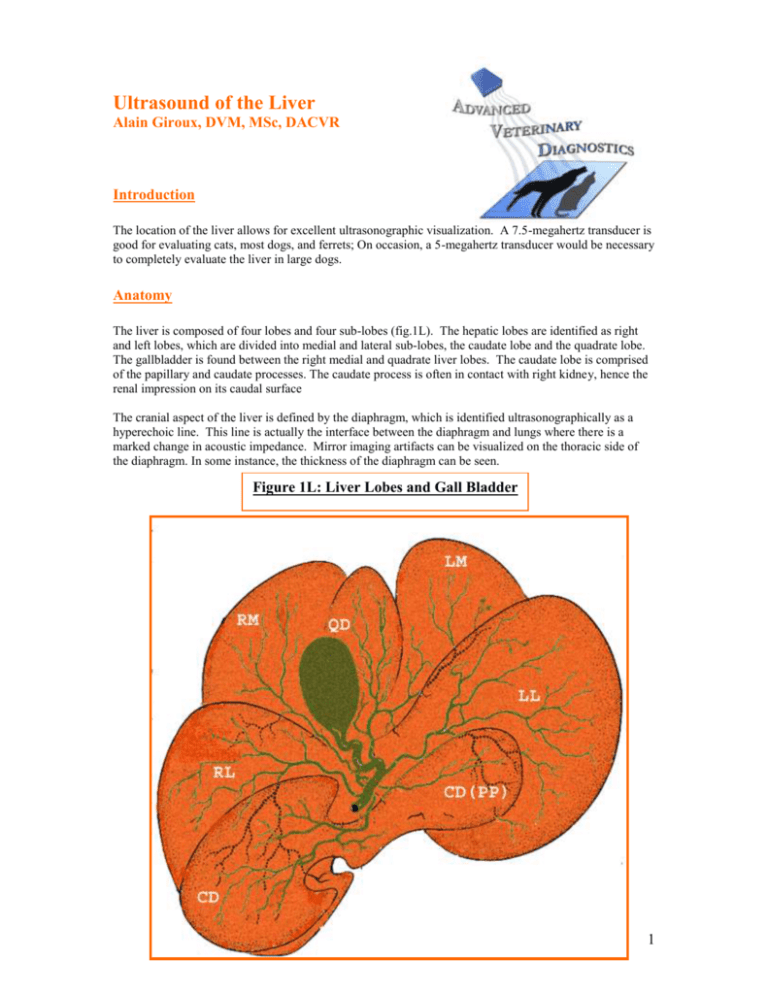

Ultrasound of the Liver Alain Giroux, DVM, MSc, DACVR Introduction The location of the liver allows for excellent ultrasonographic visualization. A 7.5-megahertz transducer is good for evaluating cats, most dogs, and ferrets; On occasion, a 5-megahertz transducer would be necessary to completely evaluate the liver in large dogs. Anatomy The liver is composed of four lobes and four sub-lobes (fig.1L). The hepatic lobes are identified as right and left lobes, which are divided into medial and lateral sub-lobes, the caudate lobe and the quadrate lobe. The gallbladder is found between the right medial and quadrate liver lobes. The caudate lobe is comprised of the papillary and caudate processes. The caudate process is often in contact with right kidney, hence the renal impression on its caudal surface The cranial aspect of the liver is defined by the diaphragm, which is identified ultrasonographically as a hyperechoic line. This line is actually the interface between the diaphragm and lungs where there is a marked change in acoustic impedance. Mirror imaging artifacts can be visualized on the thoracic side of the diaphragm. In some instance, the thickness of the diaphragm can be seen. Figure 1L: Liver Lobes and Gall Bladder 1 The hepatic arteries and the portal veins supply the blood to the liver. The hepatic veins drain into the caudal vena cava at the level of the diaphragm. The porta hepaticus or the holus of the liver contains the portal vein (before branching), hepatic arteries and nerves and the bile duct. The portal vein is identified ventral to the caudal vena cava and slightly more on the mid-line. The bile duct (Fig. 2L) is identified ventral to the portal vein. The bile duct enters the duodenum at the major duodenal papilla. In dogs the entrance of the bile duct and pancreatic duct are separated. In cats, the bile duct and pancreatic duct join before draining into the major duodenal papilla. Figure 2L: Biliary System Anatomy 2 Ultrasonographic Anatomy The liver is usually imaged with the patient in dorsal recumbency through the ventral body wall. If the liver is decreased in size or the patient is a deep-chested dog, a transcostal approach may be necessary to evaluate the liver. Specific parameters to characterize with precision and objectively the liver size have not been established. Subjective assessment of liver volume can usually be made. Since the liver is located cranial to the stomach, gas or ingesta in the stomach can hamper assessment of the liver. In deep-chested dogs, the chest wall can render evaluation of the lateral aspects of the liver and gall bladder more difficult. The individual hepatic lobes are not identified ultrasonographically unless peritoneal fluid is present. Localization of a hepatic lesion can be aided by the fact that the gallbladder divides the liver into the right and left liver lobes. The quadrate lobe is located ventral and to the left of the gallbladder. The right wall of the gallbladder contacts the right medial liver lobe. The caudate process of the caudate lobe contains the renal fossa and is just cranial to the right kidney. The gastric fundus is caudal to the left lateral liver lobe. The normal hepatic parenchyma (Fig.3L and 4L) has a uniform moderate level of echogenicity. Hepatic echogenicity is slightly more than the cortex of the right kidney and less than the spleen. Comparison of hepatic echogenicity to the spleen should be at the same depth of imaging. The hepatic echotexture appears slightly coarser than the spleen. The hepatic and portal veins are easily recognized. The walls of the portal veins are hyperechoic due to fat adjacent to the walls. The hepatic veins are best visualized as they enter the caudal vena cava near the diaphragm. The walls of the hepatic veins are not visualized unless they are large and near the diaphragm. The hepatic arteries are more difficult to identify because of their size and poorly visualized walls. However, the main hepatic artery can be identified fairly easily using Doppler. Figure 3L: Normal Canine Liver: Sagital View Figure 4L: Normal Feline Liver: Sagital View 3 The gallbladder is an anechoic round to oval structure identified to the right of the midline (Fig.5La and 5Lb). The size of the gallbladder can vary and usually depends on when the patient last ate. The wall of the gallbladder is very thin and can be visualized as slightly hyperechoic to the hepatic parenchyma. Echogenic material which gravitates to the dependent portion of the gallbladder (sludge) can be seen and is usually of no clinical significance. Acoustic enhancement is usually identified distal to the gallbladder. The intra and extra hepatic biliary ducts are not visualized in normal dogs. The cystic duct connects the gallbladder with the duodenum. The bile duct can be visualized ventral to the portal vein (fig.6L) in cats. The bile duct is quite difficult to identified in normal dogs. The normal bile duct diameter is less than 4 mm in cats and less than 3 mm in dogs. Figure 5La: Normal Gall Bladder Figure 5Lb: Normal Gall Bladder Figure 6L: Feline Hepatic Hilus 4 Hepatic Abnormalities Pathology of the liver is usually divided into focal or diffuse diseases. Ultrasound is more sensitive for identifying focal lesions where there is change in hepatic echogenicity and/or architecture. For diffuse diseases, the hepatic parenchymal echogenicity must be compared to adjacent structures such as the right kidney and spleen and also to the gall bladder wall and the walls of portal vein and its tributary. If the liver is small it may be difficult to obtain an image of the spleen and liver at the same depth and settings. With both focal and diffuse hepatic diseases, correlation of ultrasonographic findings with clinico-pathological data and clinical findings is important. Examples of diffuse liver disease would include cholangiohepatitis, hepatic lipidosis, diffuse neoplasia (lymphoma), or metabolic abnormalities (steroid hepatopathy). Focal hepatic lesions are easily identified. Multiple focal lesions, either hyperechoic or hypoechoic, can be seen with metastatic neoplasia. Target lesions which appear as a hypoechoic area with a hyperechoic center are characteristic of metastatic nodules. Cystic lesions, which are anechoic and thin-walled, are easily identified and show distal acoustic enhancement. Hepatic masses usually have a complex, echogenic pattern and architecture. Without biopsy, it can be difficult to separate primary hepatic neoplasia such as hepatic carcinoma (Fig.8La and 8Lb) from nodular degeneration. Hepatic cirrhosis usually results in a small liver with irregular margins; however, nodular changes can be present throughout the cirrhotic liver. In early stages, hepatic cirrhosis may appear as a very coarse parenchyma with slightly decreased volume. Figure 8La: Focal Liver Disease: Carcinoma Figure 8Lb: Focal Liver Disease: Cystic Carcinoma 5 Enlargement of the caudal vena cava and hepatic veins can be seen with right-sided heart failure (Fig. 9L). Obstruction of the caudal vena cava with a thrombus or neoplastic obstruction can also result in distension of the hepatic veins and caudal vena cava. Portal cava shunts can result in distension of the caudal vena cava. An anomalous vessel may also be identified with a portal systemic shunt. Biliary obstruction results in enlargement of the bile duct (Fig. 10L). This can result from pancreatitis or obstruction secondary to a mass lesion compressing the duct or in the lumen of the bile duct. Thickening of the gallbladder wall has been seen with cholangiohepatitis. With peritoneal fluid and/or when low albumin is noted, artificial thickening of the gallbladder can be seen and must not be misinterpreted for a disease process. Echogenic material can be seen in the gallbladder with minimal clinical significance. If echogenic material in the gallbladder does not appear to be gravity-dependent, consideration will need to be given to a gall bladder mucocele, which has been associated with clinical signs. Choleliths and gallbladder tumors have also been reported to cause biliary obstruction. With both focal and diffuse hepatic diseases, a biopsy or fine-needle aspirate of the lesion or liver would be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. Ultrasonographic guidance to obtain the biopsy or fine-needle aspirate (FNA) is less invasive than surgery to obtain material for analysis. Prior to performing an ultrasound-guided biopsy, it would be advantageous to exclude a clotting abnormality or to pre-treat the patient with Vitamin K. FNA are however only recommended when hepatic lipidosis, lymphoma or focal carcinoma are suspected. Otherwise, tissue-core biopsies are more accurate to determine the disease process at cause. Figure 9L: Hepatic Venous Congestion Figure 10L: Biliary Obstruction 6