What can we learn from Sir Thomas Browne?

advertisement

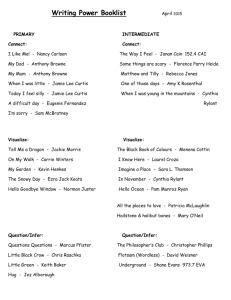

1 Bullitt History of Medicine Society February 13, 2002 Watson A. Bowes Jr., M.D. What Can We Learn from Sir Thomas Browne? As a freshman medical student I read Harvey Cushing's biography of Sir William Osler and learned that the second book purchased by Osler was an 1862 edition of Religio Medici (The Religion of a Doctor) by Sir Thomas Browne. This same volume was with Osler throughout his life and rested on his coffin along with a single sheath of lilies at his funeral. (Cushing II, p 686). This initiated my interest in Sir Thomas Browne, whom I vaguely recalled as the author of one or two examples of 17th century prose in my English Literature textbook in college. Osler was introduced to Sir Thomas Browne by the Rev. William Arthur Johnson, an Anglican clergyman, who was the founder and Warden of Trinity College School, a prep school for Trinity University in Toronto. Osler enrolled at Trinity College at age 16 intending to study for the clergy, following in his father's footsteps. While at Trinity he was captivated by Johnson's avocation as a naturalist and his encouragement of the students in observations and experiments with nature. Johnson and his wife often entertained the students at the parsonage where Johnson would frequently read aloud passages of Religio Medici. While in his second year at Trinity College School at age 17, Osler purchased his second book, the 1862 edition of Religio Medici at W. C. Chitwell's bookstore in Toronto. Slide: Religio Medici, 1862 edition. Cushing wrote that only the Bible did Osler know more nearly by heart than Religio Medic. (Cushing I, p 51) Inspired by Johnson's interest as a naturalist and his love of Sir Thomas Browne's prose and philosophy, Osler changed his career goal and, after leaving Trinity College, enrolled in the medical school at McGill University. Twenty-nine years later, in an address to medical students and faculty at McGill, Osler recalled the important influence of Religio Medici in his life: ”…no book has had so enduring an influence on my life. I was introduced to it by my first teacher, the Rev. W. A. Johnson, Warden and Founder of the Trinity College School, and I can recall the delight with which I first read its quaint and charming pages. It was one of the strong influences which turned my thoughts towards medicine as a profession, and my most treasured copy - the second book I ever bought - has been a constant companion for thirty-one years..." Browne's Education Sir Thomas Browne, the third of four children, was born in 1605 in London. His father, a cloth merchant, died when Thomas was 8 years old, and his mother soon remarried. The record is mixed about whether Thomas's stepfather misappropriated the children's inheritance, but there is no question that Browne was provided the best of education and maintained a good relationship with his stepfather. From age 11 to 17, Browne attended Winchester School, one of the finest in the England at the time. At age 18 he matriculated at Broadgates Hall, Oxford, which during his time became Pembroke 2 College. A measure of Browne's academic achievement was that he was selected to give the student oration at the inauguration ceremony for the new college. (Finch, p 42-53) Although Browne achieved an impressive classic education at Winchester and Oxford, the latter was no place to obtain training in Medicine. William Harvey's description of the circulation of the blood (De Motu Cordis) published in 1628 was not mentioned in the Oxford medical curriculum 20 years later and students learned the texts Hippocrates and Galen. Dr. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689), one of the leading physicians of the time, said, "One had as good send a man to Oxford to learn shoemaking as practicing physic." (Severn) Consequently, after a year of brief apprenticeship with one or more practitioners in or near Oxford and a trip to Ireland with his stepfather, Browne went to Europe to continue his medical education. He was there from 1630 to 1633 spending approximately one year each at the University of Montpellier in the south of France, the University of Padua in Italy, and the University of Leiden in Holland. (Hughes) These were the acknowledged centers of excellence in medical education. Montpellier was in its waning years of importance. Also medical education there was affected by the common belief that dissection of the human body was sinful. At Monpellier only one autopsy was performed each year. The University of Padua, where William Harvey obtained his medical degree in 1602, was the most celebrated medical school at that time. Leiden was ascending in reputation when Browne matriculated and obtained an MD on December 21, 1633 after defending his thesis, the title and subject of which have not survived. The medical education at Leiden placed a much greater emphasis on clinical teaching than at other medical schools in Europe. (Sugarman) When Browne was pursuing his medical studies abroad, Europe was in the midst of the Thirty-Years War and bubonic plague. Ten years before Browne arrived in Montpellier, the city, which was largely Huguenot (Protestant) was laid waste by the army of Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu. In 1629, the year before Browne’s presence there, the plague infected the population and 2000 deaths occurred. Scarcely a year before Browne went to Padua a third of the population of the region had died of the bubonic plague. His education at Winchester, Oxford, and the several European universities had served him well. He had read widely and was fluent in Greek, Latin, English, French, Italian, and Dutch and could read Hebrew, German and Spanish as well. He was a keen observer, interested in any almost any subject that crossed his intellect and was deeply concerned about the most vexing philosophical and theological issues of his day. Perhaps the most surprising thing about his life is how little some of the most “important” events seemed to be of concern to him: the civil war in England, the thirty years war in Europe, and the plague in Europe and England. These events were seldom mentioned at any length in his published work or his correspondence Upon returning from his medical studies in Europe, Browne was obliged to practice under the supervision of a well-established doctor before being licensed to practice medicine. Where this preceptorship occurred is not entirely certain, and the name of Browne’s preceptor is unknown. There is nothing in Browne’s own writing that identifies where he was during these years. A number of accounts of Browne’s life assumed that he was living and practicing near Halifax in Yorkshire; but one of the most conscientious Browne scholars, Frank Livingstone Huntley (University of Michigan) summarized the evidence as pointing to Browne’s have been somewhere Oxfordshire 3 (Huntley pp. 90-98). Whatever the case, the importance of these four years is that it was during this time that Browne, before the age of 30, wrote Religio Medici, the book that was to earn him a secure place in literary if not in medical history. Lesson: If you believe that the events of your life will be of any interest to posterity, and you are concerned about the record being accurate, write the facts down in some form while you still have the wit and energy to do so. Browne’s medical practice and family In 1637 at age 32, having completed his apprenticeship, or his residency as it might be regarded today, Browne received the Oxford degree of MD and became a licensed physician. The same year, upon the urging of friends from his Oxford days, he moved to Norwich, where he resided and practice until his death in 1862 at age 77. In 1641, at age 36, Browne married 20-year-old Dorothy Mileham. Browne’s good friend and earliest biography, the Rev. John Whitefoot, commenting upon the match said: “Mrs. Browne was ‘a lady of such symmetrical proportion to her worthy husband, both in the graces of her body and mind, that they seemed to come together by a kind of natural magnetism.’” (Gosse p. 24) Browne's decision to marry is often viewed in the light of his comments in Religio Medici about marriage: "I was never yet once, and commend their resolutions who never marry twice, not that I disallow of second marriage;… I could be content that we might procreate like trees, without conjunction, or that there were any way to perpetuate the world without this triviall and vulgar way of coition; It is the foolishest act a wise man commits in all his life, nor is there any thing that will more deject his coold imagination, when hee shall consider what an odde and unworthy piece of folly hee hath committed…." (II, 9) Nothing is known of Browne' s courtship of Dorothy Mileham or whether she was aware of what Browne had written about marriage in Religio Medici. If she was aware of it, she must have found it humorous that he so willingly joined with her in "this triviall and vulgar way of coition" to produce 12 children. Lesson: Love trumps the best intentions. Or as Pascal wrote: "The heart has its reasons of which the reason knows nothing…" (Pensées #477) Of the Browne's twelve children, including twins who died in infancy, only four, a son and three daughters, survived their mother and father. It is clear, from the correspondence of Thomas and Dorothy Browne to each other and to their children as well as from recollections of family friends, that theirs was a loving and devoted family 4 characterized by deep mutual respect. Dorothy Browne must also have been a patient and devoted wife, having indulged her husband in his huge collection of books and specimens that were stored throughout their home in Norwich. Through his correspondence and other documents, we know that Browne was a successful, busy, and humble practitioner, a respected authority in the community and a generous philanthropist to church and educational and civic institutions. Brown was an omnivorous reader, and his library contained most of the important medical tests of his time including De Motu Cordis, which was published in 1628. It is clear that he was conscientious about his own life-long professional education. Characteristic of the state of knowledge about disease and therapeutics in the 17 century, the treatments Browne prescribed were intended primarily for the relief of symptoms rather than to cure disease,. In a very interesting letter of consultation, written entirely in Latin, Browne offered advice to another physician about a patient with a perplexing condition of edema, leg ulcers and a rash. Browne called the condition “scorbutic miasma” and recommended treatment that included 41 medications, all of which were in the official pharmacopoeia of his day, but none of which would be used to day to treat any condition or even be recognized by medical students in their course in Pharmacology. Browne’s extensive correspondence with his son, Edward, also a physician, shows that Browne was familiar with a wide range of geriatric, pediatric, obstetric, and gynecologic conditions. Among his interests were disorders of the mind. In an in-depth analysis of Browne’s writings, Dr. Jerome Schneck, a psychiatrist in New York, found that Browne's insight about psychiatric illness was considerably ahead of his time. As some evidence of his esteem as a physician, Browne was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1664. In 1671, at age 66 Browne was knighted by King Charles the II. The record shows that the King had intended to bestow the honor on the Mayor of the city, who declined, and Browne was proposed as a substitute. (Patrides. Above Atlas p 21). Although Samuel Johnson believed that the honor was given to Browne for his literary celebrity, it is more likely that it was for his loyalty to the crown during the civil war. Browne was one of 432 prominent citizens of Norwich who in 1643 refused to subscribe to a fund to assist Parliament, led by Cromwell, in its war against King Charles I. One of the more controversial aspects of Sir Thomas Browne's life and character involve his participation as an expert witness in the trial of Amy Duny and Rose Cullender, two women accused of bewitching children. On March 10, 1664, the women were found guilty and hanged. Browne’s role in this sad event has been variously characterized as, on the one hand, an example of his narrow-minded acceptance of erroneous religious superstitions, and on the other hand, entirely in keeping with the prevailing attitudes about witchcraft in his time. Of interest, this event in Browne’s life was not mentioned in the short biography of his life by Samuel Johnson, written some 70 years after Browne's death, suggesting that Johnson assumed that this matter did not reflect either for good or ill on Browne's character. There is considerable disagreement among scholars about the nature and influence of Browne’s testimony. The only extant description of the events (in William Cobbett's State Trials) states that Browne testified not only on the subject of bewitchment but also that he was clearly of the opinion that the women were bewitched.(Bennett, pp. 11-17) Browne’s belief in witchcraft and witches was stated in Religio Medici: 5 “For mine owne part, I have ever beleeved, and do now know, that there are Witches: they that doubt of these, do not onely deny them, but Spirits; and are obliquely and upon consequence a sort not of Infidels, but Atheists” (I, 30) Belief in witchcraft was common in the17th century as evidence well respected scientists who shared this belief: Robert Boyle, Francis Bacon, and William Harvey among others. It is true that in the latter years of Browne’s life, opinion about existence of witchcraft was beginning to change. Nevertheless, between 1660 and 1718 there were thirteen books published asserting the existence of witches, and a review of the Transactions of the Royal Society up through 1678 found no repudiation of belief in witchcraft. (Bennett, p 11). It was not until well into the next century that belief in witchcraft no longer prevailed. But even then, 100 years after Browne lived, John Wesley maintained to the end of his life that to give up witchcraft was to give up the Bible. (Knott) Lesson: Testimony you give as an expert witness may come back to haunt you. Although Osler admired Browne as a competent and well-respected physician and a first-rate naturalist, he acknowledged “that as a scientific man Browne does not take rank with many of his contemporaries”. Even though not among the first rank of scientific minds of his day, Browne might have been expected to be a member of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, the oldest scientific organization in the world. The Society was founded in 1660 during Browne's lifetime to promote the natural sciences. Browne’s son, Edward, and his grandson were both physicians who, while living in London, were members of the Royal Society. There are two explanations for Thomas Browne’s having not being invited to become a member. One is that his prose style did not conform to the stated ideal of the Society: “a close, naked, natural way of speaking…bringing all things as near the mathematical plainness as they can.” (Oppenheimer) An alternative explanation is that Browne, a busy practitioner living in Norwich three hours from London, had little opportunity to attend meetings of the Society. Other prominent men of science living away from London were not invited into the Royal Society. Also, Browne, although perhaps disappointed by not being a member of the Royal Society, his relations with the Society and its members. (Bennett pp. 20-21) Lesson: When writing a scientific paper, be clear and concise and keep it simple. Brown as writer What may have kept Browne out of the Royal Society was exactly what earned him an enduring place in the history of English literature. Above all else Browne was a master craftsman of English prose. Many writers, including Samuel Johnson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Lamb, Thomas DeQuincey, and Herman Melville have 6 acknowledged their debt to Browne’s prose style; and James Russell Lowell, engaging in hyperbole, said that Browne was “our most imaginative mind since Shakespeare.” (Patrides). In the 20th century, the practicing physician who most nearly achieved Browne’s literary influence was the poet William Carlos Williams. The corpus of Browne’s writings consists predominantly of five works apart from his extensive correspondence: Religio Medici, Vulgar Errors, Hydriotaphia, The Garden of Cyrus, A Letter to a Friend, and Christian Morals. Religio Medici (The Religion of a Physician), the first of these, which was written soon after Browne returned from his medical studies in 1634 was not intended for publication. Impressively, it was written when Browne had few books and no library available to him and is, therefore a testimony to his previous extensive reading and his remarkably accurate memory. As was not uncommon at the time, copies of the manuscript circulated among friends, which resulted in many errors in the recopying. Eventually the manuscript fell into the hands of Andrew Crooke, a London book seller, who printed the first unauthorized edition in 1642 with anonymous authorship. Sir Kenelm Digby, an influential critic, obtained a copy of the unauthorized edition, began reading it after supper one evening and was so impressed that before sunup had finished the 190 page book and written a not so flattering review that was almost as long as the book itself. About 1250 copies were printed and sold rapidly encouraging subsequent printings. It was then that Browne acknowledged that he was the author and prepared a corrected manuscript that was published by Crooke in 1643. Having not intended originally for his reflections to be published, Browne was nevertheless concerned about the inaccuracies that were in the unauthorized editions. In his characteristic humility, Browne acknowledged in the preface to the revised edition that his complaints would seem ridiculous in comparison to the perversions and defamation that King Charles and members of Parliament were suffering. Furthermore, he was concerned that he would be judged by statements made in his youth, statements that did not have the benefit of the wisdom of "advancing judgement" and "maturer discernment." The authorized version quickly became a “best seller” resulting in Andrew Crooks becoming one of the leading booksellers in London. Interestingly, the engraving for the frontispiece, the picture of a man falling into the ocean from a tall rock and being saved by the hand of God, was made by Will Marshall. He had previously had engraved the portrait of Francis Bacon that was prefixed to the 1640 publication of Advancement of Learning. A copy of the original 1642 unauthorized edition of Religio Medici in the library of Dr. Meyer Friedman, a New York cardiologist, was recently sold at auction by Sotheby’s for $21,450. Pseudodoxiae Epidemica: or, Enquiries into Very many Received Tenents, and commonly Presumed Truths, commonly called Vulgar Errors, was published in 1646 when Browne was 41 years old. This volume, which was more than 600 pages in length, was his major work and his best seller. It was a monumental effort by Browne to identify and correct all extant errors of human knowledge of his day. The book is a testament to his omnivorous reading and extensive observations as a naturalist along with remarkable organization of odd bits of knowledge. He wrote with authority on vegetables, insects, Jews, swimming and floating, mermaids, the Red Sea, hieroglyphical pictures of Egyptians, the death of Aristotle, Methuselah, elephants, and the Tower of Babel to mention just a few things. Today, many regard the work as quaint and of only historical 7 interest. Some scholars, on the other hand, claim that in Vulgar Errors Browne is at his best in dispelling the common superstitions and traditional misunderstandings not only of the common people but also of some of the most enlightened minds of his day. And in doing so he “helped man look out upon the world with a saner eye.” (Cawley) Hydriotaphia. Urne-Buriall or, A Brief Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes Lately Found in Norfolk was written as a result of Browne’s avocation of collecting antiquities, coins and other artifacts found in excavations. In 1657 an excavation in Norfolk turned up 40 to 50 urns containing human bones and ashes along with ornaments of ivory and brass and a single opal. These items were given to Browne because of his interest in such artifacts. Hydriotaphia, published in 1658, was a compilation of Browne’s research on the history and significance of the burial urns as well as a treatise about the burial rights and traditions of ancient and modern civilizations. The Garden of Cyrus or, The Quincuncial , Lozenge, or Net-Work Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially, Naturally, Mystically Considered was published in the same year. This was a treatise not only on the five-point arrangements in the ancient Babylonian gardens of Cyrus but of the gardening customs and horticulture all manner of ancient and modern communities. Commenting on The Garden of Cyrus, Samuel Johnson said, "Some of the most pleasing performances have been produced by learning and genius exercised upon subjects of little importance." Clearly, Johnson was impressed with Browne's prose in this treatise, but not with his subject matter. Some of the finest examples of Browne’s prose craftsmanship are found in these two monographs and they can both be read with great enjoyment without any regard for their esoteric subjects. Samuel Johnson, perhaps the most learned man of the 18th century, and himself a master craftsman of English prose, was vexed that Browne’s “exuberance of knowledge, and plentitude of ideas sometimes obstruct the tendency of his reasoning, and the clearness of his decisions…” He described Browne’s style as “vigorous, but rugged; it is learned, but pedantick; it is deep, but obscure; it strikes, but does not please; it commands, but does not allure…” Johnson lamented that in the 17th century the language lost “the stability which it had obtained in the time of Elizabeth”, and he noted the multitude of exotic words that Browne had introduced. Johnson acknowledge that the new words used by Browne had augmented philosophical diction, and he conceded that Browne’s uncommon words were necessary to adequately express his uncommon sentiments. Examples of words first used by Browne are funambulatory, pinax, digladiation, embasement, discruciating, peregrinations, opprobious, callosity, diuturnal, electricity, and hallucination. Interestingly, Browne’s correspondence with his family members reflects none of the characteristics of his major literary works. It is concise, to the point, and without the use of language crafting so characteristic of Religio Medici and his other published writings. A Letter to a Friend and Christian Morales were published after Browne’s death. A letter to A Letter to a Friend, upon occasion of the Death of his Intimate Friend was published in 1690, eight years after Browne died. Browne’s biographer, Edmund Gosse said that “some of Browne’s most judicious admirers have not hesitated to place [A Letter to a Friend] on the highest level of his compositions. It was written in 1672, and although intended as message of consolation and sympathy, it was the occasion for Browne to describe his views on disease, suffering and death gleaned from his long experience of caring for patients at the end of their lives. Christian Morals was 8 published in 1716 from a manuscript that had been found by Browne’s son, Edward. Apparently it was Browne’s attempt to continue what he had written in Religio Medici leavened by years of experience and reflection and extensive reading. Browne's extensive reading and interest in so many and diverse subjects throughout his life are reflected in his writings. Reflecting this example, Osler recommend to medical students and physicians that they read from the classics one-half hour at the end of each day. (Osler. Aequanimitas back page) Lesson: An essential in the development of a well-educated physician is a lifetime of reading and studying subjects beyond the requirements of the profession. In the interest of full disclosure, I must confess that not everyone is as taken as I am with Sir Thomas Browne. In an article in the Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Dr. Perry Hookman of Cheverly, Maryland describes Religio Medici as "a dark book filled with sanctimonious claptrap and prejudices". Hookman cannot understand Osler's intellectual debt to Browne and believes it is a tribute to Osler's tolerance and humanitarianism that he was able to rise above the prejudice and bigotry of his time in spite of Browne's being his role model. This seems an instance of Hookman having no respect for historical context, and suggests another lesson to be learned from studying Browne and his writing. In my view a much more balanced treatment of Browne's influence upon Osler is found in the book entitled Osler. Inspirations from a Great Physician, by Charles Bryan, Professor and Chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine in Columbia, South Carolina. Lesson: It is necessary to judge a person's accomplishments in the context of the culture and circumstances in which they occurred. The 17th century was the watershed for the Enlightenment and the influence of empiricism in Western culture. The seminal document of this transformation was Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning published in 1605, the year that Thomas Browne was born. Bacon’s emphasis on inductive reasoning was the foundation of modern science. Bacon insisted that the only path to truth was by way of inductive reasoning and the experimental method. Thomas Browne throughout his life and as reflected in his writing resisted the unconditional capitulation to reason as the only source of truth. In Religio Medici he attempted to reconcile knowledge acquired from the study of nature and the ecclesiastical knowledge from scripture. This coherence of sources of human knowledge was the substance of Religio Medici, which was intended to be a private exercise for his own devotion. As a result of the balance of discourse that Browne attempted to achieve, he was regarded as an atheist by some of his critics. Browne insisted that in spite of his interest in knowledge gained from the study of nature, this knowledge was incomplete and potentially incapacitating without the being leavened and enlightened by the wisdom of scripture. He was convinced that faith must be informed by reason and reason must be enlightened by faith. He was a great synthesizer able to accommodate philosophical and religious truth, Catholic and 9 Protestant doctrine. He believed that the essence of one’s faith was important and not the circumstances, and he insisted on people of all persuasions being charitable with one another. Catholics, Anglicans, and even Quakers found comfort and wisdom in Religio Medici, but the book was considered sufficiently dangerous by the Catholic Church to be placed on the Index of forbidden reading. With Anglicans and Puritans at each other’s throats, Browne assumed a courageous position of tolerance of all religions, Christian and Pagan alike. In Religio Medici he summed up his opinion about the contemporary sectarian quarrels as follows: “… particular Churches and Sects usurpe the gates of heaven, and turn the key against each other, and thus we go to heaven against each others wills.” (I, 56) Browne relied on his faith to inform him about those things that simply were an enigma to his reason. For example, he claimed that reason could not account for people born with anomalies, known in his day as monstrosities. Browne would not presume that deformed humans cast doubt on God’s perfection. Rather he would depend upon faith to see “nature so ingeniously contriving the irregular parts, as they become sometimes more remarkable than the principall Fabrick.” Browne was convinced that there is nothing in nature that is ugly simply because “nature is the Art of God.” (Religio I, 16). In short, Browne described and personally exemplified almost every person’s struggle between faith and reason. A contemporary of Browne was Blaise Pascal who was born in France in 1623 and died at age 39 in 1662. His contributions as a first-class scientist and mathematician included the proof of vacuums, the mathematical descriptions conical sections and the development of the first calculator. He also introduced the first public bus service, and invented the first wristwatch. These impressive contributions not withstanding, his major preoccupation was the reconciliation of his religious faith and his scientific intellect. At age Pascal he began writing down random thoughts and insights about his spiritual reflections that were published after his death as The Penses. These reflections were written at about the age that Thomas Browne wrote the notes that became the Religio Medici. In neither case were these personal spiritual reflections intended for publication, but they dealt with the same personal struggle with the perplexities of the mind and the soul. There is no evidence that these two men were aware of the other’s writings. But it is remarkable how similar is the essence of their contributions. Having begun with William Osler’s fascination with Sir Thomas Browne, I will end with his assessment of Browne’s importance for students of medicine. He believed that the Religio was “full of counsels of perfection which appeal to the mind of youth, still plastic and unhardened by contact with the world.” The lessons that are gleaned by studying the life and writings of Sir Thomas Browne according to Osler are “mastery of self, conscientious devotion to duty and deep human interest in human beings,” all essential qualities for the student of medicine. 10 References: Bennett J. Sir Thomas Browne. ‘A man off achievement in literature’. Cambridge. The University Press, 1962. Bryan CS. Osler. Inspirations from a Great Physician. New York, Oxford University Press, 1997 Cawley RC. The timeliness of Psuedodoxia Epidemica in Cawley RR, Yost G (eds.) Studies in Sir Thomas Browne, Eugene, Oregon, University of Oregon Press, 1965, pp. 1-40. Cushing H. The Life of Sir William Osler. Volumes I & II. Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1925. Finch JS. Sir Thomas Browne. A Doctor’s Life of Science and Faith. New York, Henry Schuman, 1950. Gosse E. Sir Thomas Browne. New York. The Macmillan Co. 1905. Hookman P. A comparison of the writings of Sir William Osler and his exemplar, Sir Thomas Browne 1995;72:136-150. Hughes JT. The medical education of Sir Thomas Browne a seventeenth-century student at Montpellier, Padua, and Leiden. J Med Biography 2001;9:70-76. Huntley FL. Sir Thomas Browne. A Biographical and Critical Study. Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press, 1962. Johnson S. The Life of Sir Thomas Browne in Patrides CA (ed.) Sir Thomas Browne. The Major Works. London, Penguin Books, 1977. MacKinnon M. An unpublished consultation letter of Sir Thomas Browne. Bull Hist Med 1953;27:503-511. Knott J. Medicine and witchcraft in the days of Sir Thomas Browne. BMJ ii;957-1049. Osler W. Aequanimitas With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. New York, McGraw Hill, Inc., 1906, unnumbered back page. Oppenheimer JM. John Hunter, Sir Thomas Browne and the experimental method. Bull Hist Med 1947;21:17-32. 11 Osler W. Sir Thomas Browne. BMJ ii;1905:993-998 (This essay appears also in Osler W. An Alabama Student and Other Biographical Essays. London, Oxford University Press, 1908, pp. 248-277. Pascal B. The Pensées. (Translated by J.M. Cohen), Baltimore, Penguin Books, 1961. Patrides CA (ed.) Sir Thomas Browne. The Major Works. London, Penguin Books, 1977. Patrides CA. “Above Atlas his shoulders.” In Patrides CA (ed.) Sir Thomas Browne. The Major Works. London, Penguin Books, 1977, pp. 21-52. Schneck JM. Psychiatric aspects of Sir Thomas Browne with a new evaluation of his work. Med Hist 1961;5:157-166. Schneck JM. Sir Thomas Browne, Religio Medici, and the history of Psychiatry. Am J Psychiatr 1958;114:657-660. Severn C (ed.) Dairy of the Rev. John Ward A.M. (1648-1679). London, 1839, p 242. Sugerman J. Striking memories of medical education: a glimpse of three physician writers. The Pharos, Winter 1987:30-35. Verney RE. The Student Life, The Philosophy of Sir William Osler. London, E & S Livingstone, Ltd. 1957. Wagley MF, Wagley PF. Comments on Samuel Johnson’s Biography of Sir Thomas Browne. Bull Hist Med 1957;31:318-326.