“Embedding” Trust in a Transnational Trade Network: Capitalism

advertisement

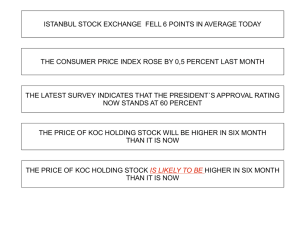

“EMBEDDING” TRUST IN A TRANSNATIONAL TRADE NETWORK: CAPITALISM, THE MARKET AND SOCIALISM Deniz Yükseker Visiting Assistant Professor, Sociology Department The Johns Hopkins University (WORKING PAPER: PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION) Deniz Yükseker “Embedding” Trust in a Transnational Trade Network: Capitalism, the Market and Socialism Deniz Yükseker* When I set out to research the informal trade network between the former Soviet Union (FSU) and Turkey in 1996, one of my research questions was based on the following. Relations between co-ethnic groups in Turkey and Soviet republics had been quickly rebuilt after a break of about 70 years, when travel restrictions on Soviet citizens were eased at the turn of the decade. It was only natural to expect that the informal trade in consumer goods in the region would be built around co-ethnic trading, given that a formal institutional framework for international trade did not exist in the region. But I discovered over the course of my fieldwork that the situation was precisely the opposite. In an important nodal point of the network in Istanbul, namely the Laleli market, buyers and sellers were not co-ethnics nor did they did not speak the same language or share the same culture. Moreover, most transactions took place informally and the legal regulation of the trade was weak. Hence the question arose: how did trade flourish in this marketplace where there was neither legal regulation of transactions nor an overarching social structure within which exchange could be embedded? In my quest to answer this question in this article, I first describe the trade network between Turkey and the former Soviet Union. Following that, I provide a historical background of the regional economy that includes Turkey and the Soviet Union. Then, I draw a conceptual framework to understand the prevalence of informality. My argument is that this trade network is a transnational informal economy. Building on Braudel’s conceptual * Mellon Fellow, Institute for Global Studies in Culture, Power and History, The Johns Hopkins University. The author wishes to thank MEAwards, the Middle East branch of the Population Council for a research grant in 1996-97 that supported the fieldwork for this study. 2 2 Deniz Yükseker framework, I situate this phenomenon at the level of the “market economy” in contrast to the monopolistic top level of “capitalism,” the layer in which economic globalization is considered to be taking place. Finally, I examine exchange relations in the main node of the trade circuit in Istanbul, the Laleli market. I focus on credit mechanisms, the cash flow and patterns of repeat trading. I argue, first, that social relations are purposefully “invented” in the marketplace in order to facilitate exchange. This entails both gendered trading practices and the creation of “trust” among buyers and sellers. Trust here does not denote an enforceable principle, but is part of an eclectic amalgam of ways of doing things in small-scale business in Turkey and Russia. Second, I problematize the concept of trust in the new economic sociology by bringing a temporal element. Specifically, I argue that the social relations within which exchange is immersed in this trade network are further “embedded” in a broader structure, namely regional and global economic conditions. Thus, intentionally invented social relations based on “trust” are weak in the Laleli marketplace, not only because of the lack of previously existing social ties; but more importantly, because of the ups and downs in the broader economy within which this trade network is located. In conclusion, I argue that the new economic sociology suffers from an exclusively micro focus and that the field would benefit from situating its analyses within the framework of the global economy. Specifically, I emphasize that attention should be paid to the interactions between the top levels of the world economy and the layer of competitive exchange relations that lie below it, namely between what Braudel calls “capitalism” and the “market economy”. 3 3 Deniz Yükseker Shuttle Trade1 Istanbul and within it the neighborhood of Laleli became a thriving node of a trade network during the 1990s that emanated from former Soviet republics. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people “shuttle” between ex-Soviet cities and cities in the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and South and Southeast Asia to purchase goods such as garments, shoes, processed food and household goods for resale back at home. The shuttle trade that takes place between Turkey and the FSU is unregistered for the most part, evading taxes and customs duties, as the involved states are either unwilling or unable to regulate it. Home to the majority of shuttle traders (chelnoki), Russia for instance allowed billions of dollars of unrecorded imports2 when the production of consumer goods plummeted after the collapse of the socialist economy at the turn of the decade, and private import companies could not replace the centralized import and distribution network of the Soviet Union. Neither customs duties, nor sales taxes were paid on the traded goods, since they were usually sold informally in open-air markets or kiosks. The shuttle traders were common people, mostly jobless or underemployed workers at various education and skill levels who took up trading when they found that surviving on state sector incomes or pensions was impossible. Turkey, on the other hand, did not regulate “suitcase trade” (bavul ticareti) – as unregistered small-scale trade by foreigners is called in Turkish – since the government perceived it as an effortless way to attract much needed foreign currency for the ailing national economy. At a high point in the mid-1990s, suitcase trade “exports” were estimated to be around $10 billion annually, a significant sum compared to Turkey’s official total The discussion in this article draws on the findings of field research I carried out in Istanbul, Turkey’s Black Sea coast and Moscow in 1996-1997, and back in Istanbul in summer 2001. 2 For instance, the OECD estimated that unregistered shuttle trade imports accounted for about one fourth of Russia’s total imports of $84 billion in 1996 (OECD 1997). 1 4 4 Deniz Yükseker exports which ranged between $20 to $30 billion per annum over the decade.3 In Laleli,4 most transactions are unrecorded, many stores are not registered and much of employment is off-the-books. The entrepreneurs and salespeople are predominantly rural migrants and immigrants from the Balkans, who have set up shop here because entry was easy due to informality. Much of the trade that goes on is not taxed; nor are the goods registered as exports when they leave Turkish customs. Shuttle traders always pay for merchandise in cash (in dollars) and therefore the money that comes to Laleli hardly enters the banking system. Informality in the marketplace has backward linkages, too. A significant amount of production of apparel, footwear and leatherwear for Laleli is undertaken off-the-books. The fact that the state has turned a blind eye on pervasive informality in Laleli has had an important repercussion from the perspective of doing business. Lack of documentation of the transactions hinders legal safeguards against all kinds of malfeasance such as defective merchandise deliveries and non-payment by the chelnoki. Uncertainty in the marketplace is compounded by the lack of policing. Traders who have to carry large sums of money on them are always susceptible to pickpockets and muggers. Hence the question arises: how are fraud and malfeasance to be avoided in a marketplace that is not formally regulated? But before attempting to answer that question, I want to provide a historical background for the emergence of this trade network, and then draw a conceptual framework to study it. 3 Since 1996, the Central Bank of Turkey makes estimations of shuttle trade exports based on surveys of suitcase traders at Istanbul’s Atatürk Airport to be used in Balance of Payments accounting. In 1996, the Central Bank figure was $8.8 billion, dropping to $5.8 billion in 1997. The Central Bank calculated shuttle trade exports to be $3.7 billion in 1998 and $2.2 billion in 1999. As the Russian economy gradually stabilized in the wake of the August 1998 crisis, Turkey’s suitcase trade earnings slightly recovered in 2000 to $2.9 billion (DPT 2001). 4 My focus on Laleli stems from the fact that this neighborhood has become both physically and symbolically the center of suitcase trade in Turkey. In fact, shopkeeping has spread to other districts and manufacturing of apparel and leatherwear for the traders takes place in peripheral areas of Istanbul. Still, Laleli is the hub of all these activities. 5 5 Deniz Yükseker The People and the History It has been argued that the Black Sea region constituted a Braudelian “world” with a single economic division of labor during the long nineteenth century (akin to the Mediterranean world in the sixteenth century) (Özveren 1997). The control exercised by the Russian and Ottoman empires over the Black Sea trade was eased, as both countries were preoccupied with imperial rivalries during this period. Thus, “political boundaries increasingly yielded to the logic of economic exchanges” in the region (ibid.: 85-86). The mobility of various ethnic groups within the region (such as Pontic Greeks, Ciscassians and Tatars) bolstered trade relations beyond the control of the states. For instance, in the first half of the nineteenth century, Trabzon’s resurgence as an important port city on the Eastern Black Sea coast was possible thanks to the construction of ethnic networks among diaspora communities such as Greeks, Armenians and Persians (ibid.: 92). Apart from the trade networks organized by imperial powers or trade diasporas, various peoples around the Black Sea were also in contact with each other culturally and economically. In the second half of the nineteenth century, several million people emigrated to Turkey from the Caucasus, Crimea as well as the Balkans due to wars, the Ottomans’ territorial losses and the creation of new nation-states. These included Circassians, Daghestanis, Chechens, Georgians, Crimean Tatars as well as Turks and Muslims from Bulgaria, Romania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Albania and Greece (Karpat 1985; Tekeli 1990). Communications between Turkey’s Black Sea coast, and the Crimea and the Caucasus were cut off in the 1920s, with the formation of the Turkish Republic on the one side and the USSR on the other. This abrupt change also severed the links between ethnic groups that occupied the regions on the two sides of the Turkish border such as Georgians, Circassians, Abkhazians, etc. When the Sarp border gate on the border between Soviet Republic of Georgia and Turkey was opened in 1988, for the first time in nearly 70 years 6 6 Deniz Yükseker relatives and co-ethnics on the two sides of the border came together. Soon afterwards, a border trade agreement between the then USSR and Turkey allowed small traders to bring in and take back goods for resale. The opening of the border and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union brought much hope that the historic regional Black Sea economy would revitalize. In 1992, at the initiative of Turkey, the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) project was initiated for the purpose of bolstering trade and investment in the region. Signed by eleven countries (Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Greece, Moldova, Romania, Russia, Turkey and the Ukraine), the BSEC project has not been very influential in bringing about economic cooperation due to the lack of an international legal infrastructure in the region and the depressed state of post-socialist economies (Gültekin and Mumcu 1996). But on the other hand, shuttle trade flourished, which was much broader in its geographical scope than the Black Sea region, and involved more people than just the ethnic groups who lived on both sides of the borders in this region. Thus, when borders were reopened, the broader transnational networks of shuttle trade enabled by air travel over vast spaces quickly overshadowed the re-emerging Black Sea regional economy. The Laleli district emerged as a transnational marketplace for shuttle traders from Eastern Europe in the second half of the 1980s. Formerly a residential neighborhood, dozens of hotels were built in Laleli in the 1980s, attracting tourists from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia who regularly visited Istanbul to buy leather coats and jewelry from the historic Grand Bazaar in the adjacent area of Beyazıt. The removal of travel restrictions and the ensuing collapse of the state-led economy resulted in a stream of shuttle traders from the Soviet Union starting in 1990. By the mid 1990s, nearly 1.5 million people from the FSU visited Turkey annually; most of them repeat comers to Istanbul (DIE 1997). Their onslaught to Laleli brought about a mushrooming of stores which catered to their demands in much 7 7 Deniz Yükseker needed consumer goods such as clothing and shoes as well as much desired ones such as leather and fur coats and golden jewelry. In just a few years, Laleli turned into the center of suitcase trade in Istanbul. Stores mediated between small-scale informal manufacturers of apparel and footwear in the city and the Russian-speaking customers who shuttled back and forth from the FSU. Among the shuttle traders who visited Istanbul regularly, the ones from Slavic republics – Russia, the Ukraine and Belarus – were overwhelmingly5 women, while the ratio of men was higher among those from Muslim republics. Women’s predominance was related to with their overrepresentation among the unemployed and underemployed (Rzhanitsyna 1995; Attwood 1996; also Yenal 2000), which had led them into informal income-earning strategies including shuttle trade. Similar to the chelnoki, most of the shopkeepers and their workers in Laleli were not “locals.” The majority were Kurds from Turkey’s eastern and southeastern provinces, and immigrant groups from the Balkans, such as recent Turkish emigrants from Bulgaria and second generation Bosnian and Macedonian immigrants. As opposed to the shuttle traders, the shopkeepers and workers in Laleli were overwhelmingly male. What brought Turkish and Muslim immigrants from the Balkans to Laleli was their ability to speak Russian and other Slavic languages. The medium of transactions in Laleli is Russian and all stores employ Russian-speaking salespeople. The pioneers in shopkeeping in Laleli back in the 1980s were Bosnians, who had started as interpreters for Polish shopping tourists. More importantly, by the mid-1990s, Kurdish migrants came to constitute the majority of shopkeepers, many of whom pushed to the informal economy of Laleli because of the dearth of meaningful income-earning opportunities in the city due to their lack of skills, including Turkish language skills. 5 A survey by Blacher (1996) showed that 85 percent of the chelnoki were women. The results from my unrepresentative survey of 168 chelnoki in Istanbul and my observations during the fieldwork were similar. 8 8 Deniz Yükseker In Laleli, I found very few members of ethnic groups that have populations both in Turkey and in Russia and in the former Soviet Union. For instance, there appeared to be very few Circassians, Osetians, Abhazians, Georgians, Azerbaijanies, etc., which are ethnic groups native to the North Caucasus and the Transcaucasus, and have significant diasporic communities in Turkey (Karpat 1985; Shami 1998, 2000). I met an Azerbaijani entrepreneur in Laleli, who proudly claimed to be the only storeowner in the neighborhood from his country. Ironically, his business partner in Istanbul was a Syriac Christian from the province of Mardin; and all his business, he said, was with Russians. There were many salespeople from Azerbaijan, but they worked as hawkers for shops located in upper floors of buildings that could not catch shoppers’ attention. As diasporic communities in Turkey rebuilt their relations with their homelands in Southern Russia and Azerbaijan in the course of the 1990s, they also created economic ties. However, those ties were usually in the form of direct investments and formal international trade. In other words, these people were not involved in shuttle trade. If we look at where the shuttle traders come from, the lack of co-ethnic trading becomes more obvious. The majority of shuttle traders are from the Russian Federation. The majority of the respondents to my survey were in fact from Moscow and Siberian towns. Ethnically, they were predominantly Russian. In fact, the sheer number of people who shuttle to and fro foreign countries defies any attempt to study suitcase trade as the reincarnation of historic trade routes in the region. Russian authorities estimated in the late 1990s that more than one million people were engaging in shuttle trade from abroad ((ITAR-TASS 1997). Hence, there were no trade diasporas operating in the networks of shuttle trade, akin to the historic role of ethnic minorities in long distance trade (Braudel 1982; Curtin 1984; for contemporary examples see Kyle 2000 and Diouf 2000). 9 9 Deniz Yükseker How can we make sense of the development of this trade network in conceptual terms? Specifically, I want to situate this phenomenon vis-à-vis economic globalization and transnationalism. A Conceptual Framework In our age, capital, goods, money and images travel around the world faster than ever before, thanks to space adjusting technologies in transportation and communications, and the concomitant integration of world markets. Scholars analyze different facets of the operation of this “global” economy. But usually, their focus is on the upper echelons, such as the operations of multinational corporations, international economic institutions, the role of the media, global financial flows and markets, global cities, and so on. However, when we examine a phenomenon such as shuttle trade, we see that it does not belong to the top-level circuits of capital, money and goods. On the contrary, the cross-border movements of ordinary people weave this trade network. I have found Fernand Braudel’s understanding of economic life useful in bridging the gap between the lower and the upper echelons of the world economy. Braudel uses the metaphor of a building with three floors in order to describe economic life. The first floor is material life; the second level is the market6; and capitalism is located on the third floor. The market has always been a zone of small profits and high competition, whereas capitalism is a zone of extraordinary profits, high capital formation, concentration, and a high degree of monopolization (Wallerstein 1991: 209-211). The market economy, “with its many horizontal communications between the different markets” (Braudel 1982:229) predates the capitalist world economy. As the anti-market, capitalism has always depended on state power for its emergence and growth (Arrighi 1994:10). Studies on globalization, transnationalism and the 6 I italicize market economy as defined by Braudel in order to avoid confusion with other usages of the term market, such as “market” as a marketplace, “a free market economy”, “a national market”, “transition to market economy”, etc. 10 1 0 Deniz Yükseker ongoing transformation of the world economy usually scrutinize this top floor, such as the activities of multinational corporations (MNCs), global financial and commodity flows, or global cities (e.g. Hirst and Thompson 1996; Arrighi 1994; Sassen 1991; Castells 1996; Lash and Urry 1994). Braudel argues that the recovery in European economies in the fifteenth century, and later in the seventeenth century were largely the work of trading at lower levels, such as markets, shops and peddling. In the sixteenth century, however, economic progress was achieved “from above, under the impact of the top-level circulation of money and credit, from one fair to another” (Braudel 1982:135). Beginning in the early eighteenth century, the anti-market started to confront the market, i.e., warehouses and wholesale trade began to replace fairs, and banks and the stock exchange increasingly took over credit functions. Gradually capitalism imposed its rule over the entire economy of Europe, including the infrastructures of everyday economic life, although the latter continued to have a degree of autonomy from the top level (ibid.: 136). The market economy survived and continued to flourish to this day in regions and during times when distribution systems did not work well or when there were economic downturns. I argue that, in the last three decades of the twentieth century, the restructuring of the world economy has led to the growth of the Braudelian market at a transnational level. I further argue that shuttle trade is an example of the operation of the market across national borders. The Braudelian market has spread beyond borders as a result of two processes: (i) the increasing transnational mobility of people, and (ii) the emergence of unregulated economic spaces as a result of the declining regulatory capacities of nation-states. (i) Cross-border interactions mediated through migration, refugee movements and tourism are instances of what has come to be called transnationalism. Many scholars underline that the same technological advances that have lead to the globalization of capital and money flows also facilitate the formation of transnational social spaces, in which people, 11 1 1 Deniz Yükseker goods, ideas and images crisscross borders (for example, Portes et al. 1999; Guarnizo and Smith 1998; Basch et al. 1994; Appadurai 1996; Hannerz 1996). Transnational connections not only bring about cultural or material flows; more importantly, the goods and images that circulate are immersed in transnational social relations (Glick-Schiller et al. 1992), rather than being embedded in top-level circuits of capital and money. As such, people’s movements have become conduits for the transnational reach of the Braudelian market economy without necessarily being mediated by multinational capital. (ii) Parallel to globalization, state regulation of national economies has been eroding according some, and is being transformed according to others (Sassen 1998; Castells 1996; Carnoy 1993). States thus become unable to control some financial flows in and out of their territories, while they may deliberately relinquish regulation in some economic fields. My argument is that the Braudelian market economy thrives in spheres where states have either lost their grip and/or chosen to neglect, or where multinational capital has not yet asserted itself. How can we situate shuttle trade in light of this conceptual framework? The networks of suitcase trade are woven by the constant shuttling of people in a geography where state regulation has significantly weakened, but has not been replaced by global governance institutions, either. Pervasive informality in suitcase trade is a symptom of the weakness of regulation. However, what we observe here is not an “urban informal sector.” Shuttle trade is a transnational informal economy in which the lack of statal regulation is not simply a matter of bookkeeping. By virtue of its characteristics as highly competitive and relatively autonomous from the activities of corporate and multinational capital, this informal economy is located within the Braudelian market economy. Two qualifications are in order here. One is that, shuttle trade in Eastern Europe is not a unique phenomenon. Similar informal cross-border trade networks exist in Africa 12 1 2 Deniz Yükseker (MacGaffey 1991), between African states and Europe (MacGaffey and Bazenguissa 2000; Marques et al. 2001; Diouf 2000), within the Americas (Freeman 2000; Kyle 2000), and in East Asia (Womack and Zhao 1994). The fact that suitcase trade is not a singular phenomenon actually lends support to my argument that the Braudelian market economy has become transnationalized. The second qualifier: there’s certainly a lot of interplay between shuttle trade and the upper echelons of the regional economy. Indeed, Braudel tells us that capitalism thrives on the dynamism of the market. In shuttle trade, this interaction between the different levels takes several forms: First, corporate capital makes efforts to enter the market. Thus, some multinationals and large-scale Turkish manufacturers have taken advantage of the unregulated networks of suitcase trade in order to enter former Soviet republics’ national markets. Second, some actors within the networks of suitcase trade (especially in transportation and wholesaling in Russia) have concentrated capital to such a degree that they strive to situate themselves in a higher plain of the regional economy. States selectively support such monopolistic tendencies overtly or covertly (through corruption). Third, the shuttle trade market is ultimately affected by developments that take place in the global economy, such as changing world market conditions, financial crises and states’ responses to such crises. My focus in this article will be on the exchange relations between and among smalland medium-scale actors in shuttle trade, those who inhabit the transnational market economy, based on my observations in Laleli. However, we will also see that developments in the upper echelons, such as national economic policies and global economic conditions, also impact upon exchange within the market. 13 1 3 Deniz Yükseker Exchange Relations As stated earlier, the interface of the marketplace in Laleli is between groups of people who, ethnically, culturally and linguistically, are usually not tied to each other. To restate the question raised at the beginning of the article: what, then, holds together exchange in this marketplace? My interviews with both storeowners and shuttle traders showed that people usually did business with regular customers. For example, many suppliers of apparel and leatherwear expressed that the bulk of their sales was with repeat traders. Chelnoki likewise said that they shopped from the same stores on each trip to Istanbul. In order to get a grasp of the significance of repeat trading in Laleli, we should keep in mind what the marketplace looks like. Laleli is a neighborhood of six- to eight-story apartment buildings. During the boom in shopkeeping in the 1990s, almost all residential apartments were turned into stores. Shopkeepers use the uppermost flights of the buildings as storage, whereas cargo companies that transport suitcase traders’ merchandise use the basements. There are no sound estimates of the number of establishments in this densely built neighborhood that stretches half a kilometer long and one kilometer wide – especially because many shops are not registered. Nevertheless, it is believed that during the boom years there were more than 10,000 stores of various sizes that exclusively catered to shopping tourists (ITO 1995). Here, then, we have a very large number of shopkeepers who are in competition with each other to attract customers, and a very large group of shuttle traders who might be in competition with each other back at home to get the fastest selling models and the best quality merchandise at the cheapest prices in Laleli. This marketplace presents us with an unusual combination of situations. On the one hand, it is highly competitive and characterized by easy entry (because it is informal), 14 1 4 Deniz Yükseker reminiscent of the perfectly competitive market of neoclassical economic theory. On the other hand, the market is characterized by weak legal regulation, reminiscent of urban informal sectors. Yet, it is not an “urban” informal economy where exchange relations are usually embedded in social networks of kin or ethnic groups (Hart 1988). It is in place here to recall one of the paradoxes of the informal economy, as formulated by Alejandro Portes. “[T]he more it [the informal economy] approaches the model of the true market, the more it is dependent on social ties for its effective functioning” (1994: 430). In other words, as the state withdraws from regulating the activities in a market – hence removing distortions to perfect competition – the likelihood of defaults, fraud and foul play increases. For Portes: The dynamics of economic action that Granovetter (1985) labeled “the problem of embeddedness” are nowhere clearer than in transactions where the only recourse against malfeasance is mutual trust by virtue of common membership in a group. Trust in informal exchanges is generated both by shared identities and feelings and by the expectation that fraudulent actions will be penalized by the exclusion of the violator from key social networks. To the extent that economic resources flow through such networks, the socially enforced penalty of exclusion can become more threatening, and hence effective, than other types of sanctions (ibid.) What Portes is referring to in this context is enforceable trust and trust generated through bounded solidarity. Elsewhere, Portes and his associates describe these notions as important elements of “social capital,” resources that can be used for facilitating investments and transactions in informal economies or ethnic communities (Portes and Landolt 2000; Portes 1995; Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993). The seeming contradiction in the marketplace of shuttle trade is that, exchange takes place smoothly despite the absence of enforceable trust or bounded solidarity. Exchange is often in the form of repeat trading between pairs of buyers and sellers, and there is a constant talk about “trust”. In this instance, the seeming paradox is that market exchange is embedded in some kind of social relations despite the absence of an overarching social structure. In 15 1 5 Deniz Yükseker order to overcome this seeming paradox, I turn next to a discussion of “trust” in forming repeat trading patterns in Laleli. Trust and Distrust Storeowners and traders in Laleli often talked about the same thing: the most important trait of an entrepreneur is being trustworthy in the eyes of both suppliers and customers. The owner of a large shoe store in Laleli thought that “Russians” (meaning people from Slavic republics) were “perfect” people. “They are well educated, honest and sincere,” he asserted. He had such faith in their honesty that he said, “I am Turkish, yet I am sorry to say, I will not sell another Turk shoes on credit. But I will sell on credit to Russians.” Sometimes when a customer was short of cash, he said he would let her pay after she sold the shoes back home. A Kurdish apparel store owner (previously a cheese merchant in the southeast) put the issue of trustworthiness in starker terms: “there are hardly any bad people among Russians. They are much more honest than we are. Christians do not cheat. But Muslims, such as Azerbaijanis, do.” He explained that sometimes his customers would pay for half of the goods they bought, and pay the rest of the money once they sold the merchandise and made another trip to Istanbul. At the other extreme, I also met people who were hurt by too much faith in the trustworthiness of their customers. For instance, a small women’s apparel store owner, a Bulgarian Turk, was cheated by his regular clients. Trusting their word, he had given a whole batch of goods to be paid later to a couple from the Siberian city of Tumen. The value of the merchandise, 8,000 dollars, was equal to his working capital. The couple never came back. When I talked to him in the winter of 1997, he had closed his store and was hoping to travel to Siberia to find that couple. Wishful thinking, his friends thought. But were the storeowners trustworthy themselves? Here again, stories of honesty and dishonesty were intertwined. Some shopkeepers complained that during the formation of the 16 1 6 Deniz Yükseker Laleli marketplace in the early 1990s “dishonest” entrepreneurs regularly cheated shoppers by selling defective clothing or overcharging after promising a lower price. It had become a cliché that “bad” shopkeepers – parallel to the general social prejudices, who were seen as Kurds or recent rural migrants lacking experience in shopkeeping and trade – were “ruining Laleli.” For instance, the owner of a small leatherwear store, who had been in the garment sector for two decades, made the following remarks: “There are some shopkeepers who have come from the village and set up shop with their little savings. But they do not know the business. That is, they try to sell defective merchandise to customers and scare them away.” He stressed that for one to create a regular clientele, “trust” (güven) was indispensable. Boasting that most of his business was with regular customers, he said: “If I hurt a customer once, she will not come back again. Those who sell defective goods cannot survive in Laleli.” Likewise, several Bosnian business owners in Laleli, who were among the first to open apparel stores for shopping tourists in the mid 1980s and who had since turned their establishments into large-scale export companies, asserted that their success was based on honesty and trustworthiness towards their East European customers. The comments of shuttle traders, too, ranged between full trust (doverie) in their Turkish7 business partners and distrust towards cheaters. Chelnoki who said they completely trusted their partners said that Turkish people are usually “fair”, “good” and “honest” people. Some of them pointed out the importance of having shopped at the same store for a long time as the reason why they trusted a particular shopkeeper. A woman I interviewed in Moscow in 1997 talked very strongly about the issue of trustworthiness: “Of course I trust my partners. How else could I work with them?” But there were others who expressed less then full trust in the shopkeepers, citing the sale of defective or low quality merchandise. 7 I use the word Turkish to denote citizens of Turkey, rather than people of Turkish ethnicity. 17 1 7 Deniz Yükseker Thus, the stress on the indispensability of trust for both the chelnoki and the shopkeepers appeared to be entangled with the complaints about the lack of it. Does trust, then, really exist in Laleli? And if so, what does it denote? It certainly is not enforceable trust. If someone runs away without paying for delivered merchandise or another person fails to deliver goods that are paid for, there is no social network spanning buyers and sellers in different countries within which sanctions against malfeasance can be enforced. I argue that “trust” in Laleli is the product of the coming together of two different sets of understandings of this notion, emanating respectively from small-scale business practices in Turkey and informal economic activities in Russia8. As such, it lubricates market exchange in Laleli by creating repetitive exchange among pairs of buyers and sellers. Yet, this principle of “trust” is susceptible to abuse by both sides of the exchange relationship. In order to demonstrate this argument, I first describe the notion of trust in small-scale trade in Turkey. Within this context, I examine the credit and cash flows within the Laleli marketplace. Then, I discuss the social relations within which informal activities take place in Russia. “Güven” in Small-scale Trade in Turkey An apparel manufacturer who produced women’s wear for stores in Laleli remarked on the notion of güven in small business in Turkey in the following way: “The apparel sector depends on trust. There may be ebbs and flows. It is a risky business. Trust and risk-taking go together.” In the chain from manufacturing apparel to wholesaling and retailing it, each person counts on (trusts) the next one in line for successful sales. If there is failure at the final loop of the chain, it trickles back down the line. In the language of small business in Turkey, this is called operating on an “open account” (açık hesap) where payments always depend on 8 I confine this discussion to Russia, both because Russians are the majority among the chelnoki and since the scholarly literature on that country is richer than other former Soviet republics. 18 1 8 Deniz Yükseker the overall performance of the market. This man explained that in Laleli, just as in the domestic market, many storeowners operated on güven, and therefore on “open accounts”. Trust, then, was a willingness to take a risk in establishing repeat trading with suppliers and customers. The following examples demonstrate this point. In 1997 I met several Bulgarian Turks who had recently opened small stores in Laleli, after having worked as salespeople. They did not have much start up capital; yet, not only had they earned the “trust” of manufacturers, but they also had acquired regular customers among the chelnoki. One young man was selling women’s t-shirts. He said that he had regular customers, women whom he had met more than a year ago when he used to work as a salesperson. He had managed to attract their business to his store. According to him, having a large start-up capital was not all that important in Laleli. “It is possible to become rich even in two months, if you know people and if you have customers, ” he asserted. Another man had opened a store with his friends in 1995 when he was only twenty years old. They gathered their savings together totaling DM 3,600 and rented a small store. The leather coats in the store were acquired on an open account. This man explained that, while working as salespeople, they had come to know a leatherwear manufacturer who agreed to give merchandise on credit to them. Alluding to Portes (1994), in this informal economy, precisely because the market is reminiscent of the theoretical model of the perfectly competitive market, actors need to get into social relations. Since there are too many competitors and too little regulation of the market, one wishes to hold on to a business partner, if the initial transaction between the two is mutually gainful. Let us have a closer look at how such repeat trading – what Geertz has called clientelization in the context of a “bazaar economy” (1992) – takes place. 19 1 9 Deniz Yükseker In the networks of shuttle trade between Turkey and the FSU, the predominant medium of exchange is the American dollar, followed by the German mark.9 In Laleli, all prices are posted in dollars; so much so that, people joke that even to buy a loaf of bread you would have to pay in dollars. Shopkeepers pay manufacturers in dollars, too. Much of the transactions take place in cash. But the very cash flow creates incentives for doing business on credit. In a way, the cash flow and the credit mechanism are two sides of the same coin. Analyzing exchange in a marketplace in Java, Geertz had argued that cash lubricates transactions by means of helping one get credit (1963: 39). The same principle applies in Laleli. A steady cash flow bolsters credit relations, thus establishing regular trading among pairs of buyers and sellers. In turn, the credit mechanism integrates the market. When a manufacturer gives goods on credit to a shopkeeper, a mutual dependency arises. If the shopkeeper is able to pay back, he becomes able to ask for more goods on credit. Through the same act, the manufacturer ties the shopkeeper to himself, securing a continued outlet for his products. Through repeated trading, a pattern of transactions is established between them. Likewise, credit given by a shopkeeper to a shuttle trader may create regular business among the two. If the shuttle trader pays the money she owes to a storeowner, that payment, even if partial, may secure for her another batch of goods on credit. But in shuttle trade, there is a thin line between defaulting on credit payments and being true to one’s word, since there is no enforcement against non-payments. Therefore, the amount of credit is crucial in repeat trading. If the amount of credit a shopkeeper gives to a suitcase trader is too high, that increases the likelihood of default; alternatively, if it is too small, the chelnok will not feel obliged to come back to the same store during her next trip to Istanbul. The words of a cautious small storeowner in Laleli echo the importance of this 9 In Russia, in marketplaces and kiosks where shuttle traded goods are sold, the ruble is used because laws forbid the usage of foreign currency in all transactions. However, prices always reflect their dollar value. 20 2 0 Deniz Yükseker point: “If someone owes you even as little as 30 dollars, she will not come back to your store. She will go somewhere else the next time. It is better to give her a 30-dollar gift. Then she would come back.” Nevertheless, many storeowners conceded that they would normally give credit up to 30 percent of the value of a batch of goods someone bought, provided that she was a regular customer. The incentive to give merchandise on credit arises from the need of the supplier to tie a customer to himself, based on the assumption that there will be a steady cash flow if they continue to do business with each other. And the incentive for a chelnok to return to the same supplier is based on the following consideration. If the goods she buys from him initially are of decent quality at a reasonable price and they sell well back at home, she will continue to shop from his store, rather than plunge herself back into the hustle and bustle of the huge marketplace on her next tour to Laleli, where information on prices, models and quality always has a cost, in terms of time and money. So, how do the shopkeepers try to get regular clients? In fact, one quickly notices in Laleli that there is a big emphasis on hospitality towards the customers, which in a way, is an extension of small-scale retailers’ practice in the domestic market of offering tea to a potential shopper. Salespeople immediately offer soft drinks to chelnoki who examine the merchandise with an eye to buying them. This must be such an important part of entrepreneurship in Laleli, that a man whose small women’s clothing store I visited listed Coca-Cola and Fanta among his operating costs. When a deal is concluded, the storeowner might offer lunch to his customers, or better yet, take them to dinner out in the city. The hospitality in some large stores goes so far as displaying in-house mini-bars where spirits (including, of course, Russian vodka) are ready to be offered. Almost all storeowners I talked to emphasized that they had friendly relations with regular customers. They helped customers in Istanbul in various ways including finding dentists, dealing with the police, dealing with 21 2 1 Deniz Yükseker hotel managements or cargo companies. Some said that they had probed into the possibility of opening stores in Russia or other republics in partnership with their suitcase trader customers. This emphasis on friendly relations was indeed corroborated by many chelnoki. Some even mentioned that they had hosted their Turkish business partners in their hometowns. If one end in the spectrum of social relations that sustained market exchange in Laleli is simple hospitality towards clients, the other extreme is occupied by romantic involvement between male suppliers and female chelnoki. I have examined elsewhere the consequences of gendered trading in Laleli in a situation in which storeowners with traditional upbringing and little education perceive Slavic women to be industrious, enterprising and very attractive elsewhere (Yükseker, forthcoming). Here, I confine my remarks to how market exchange may sometimes be “embedded” in romantic relationships. Although both men and women were tight-lipped about this issue, my impression is that romantic relationships in Laleli help build repeat trading patterns. A female trader might regularly shop from her boyfriend’s store. A shopkeeper can provide his girlfriend with much needed connections in a foreign environment. For example, he may help her bargain with other shopkeepers; he might help her if she gets into trouble with the police or the customs. More importantly from our perspective here, romantic involvement is likely to make credit available for a female chelnok. A young shopkeeper conceded to me that he sometimes gave merchandise on credit to his Russian girlfriend, “but it wouldn’t exceed several hundred dollars,” he stressed. Yet, he said that he also lent money to other female customers when they complained of having run out of money, “because, he is soft-hearted”. In fact, one often hears stories migrant shopkeepers who get “fooled” by the female traders’ beauty. One man expressed this in the following way: “Russian women are beautiful and too liberal. This has an impact on Turkish men.” “Some shopkeepers give merchandise on credit to young and 22 2 2 Deniz Yükseker beautiful Russian women because the women sleep with them,” another man told me. He also said that he know storeowners who had given substantial amounts of credit to female customer/lovers and went bankrupt when the women did not pay back the money. Still, we should be cautious about making a generalization regarding the link between romance and business. Although the majority of shuttle traders are women, there are many among them who are accompanied by husbands or boyfriends, who complain about unwanted sexual approaches by men in Laleli, or who describe their interaction with the shopkeepers as “based on mutual respect.” Likewise, many merchants speak critically of the harassment of women on streets and some even attribute the decline in the numbers of chelnoki in the last few years to the behavior of unruly men. But the importance of gender in informal shuttle trade is very central to the discussion in this article for an entirely different reason. Men and especially women have been socialized in ways of doing things informally since the days of the socialist economy. And, it is at this point in the discussion that we should examine the notion of “trust” from the perspective of the chelnoki. “Blat” Exchange and Trust in Russia Although we are more likely to hear in the media about the predominance of the mafia in Russia’s new capitalist economy, “trust” is an important tenet in small-scale entrepreneurship. “Transition to market economy” in the former Soviet Union and specifically in Russia has been a bifurcated process. On the one side are the “New Russians,” a predominantly male group of entrepreneurs who have got the upper hand during the privatization of state companies and/or had access to capital by virtue of their previous positions within the Soviet system. To a great extent, big private business in Russia is entangled with the mafia and protection rackets (Sterling 1994). Thus, far from a reliance on trust, Russia’s new capitalism substitutes the lack of formal and informal (social) regulation 23 2 3 Deniz Yükseker with the use of force, that is, organized crime. On the other side are people who seek to complement wages or earn a living by resorting to small- and medium-scale entrepreneurial activities, ranging from selling small items at subway stations to shuttle trading abroad. Small entrepreneurs usually evade taxation and therefore official regulation (Schroeder 1996), while simultaneously struggling to stay away from protection rackets. Small-scale exchange practices in Russia today are influenced by the ways of doing things that people were accustomed to within the “second economy” (informal economy) of the Soviet period. Here, one important practice stands out, namely, the blat system of informal transactions. Blat is a form of exchange characterized by reciprocal dependence, and it engenders mutual trust over the long term. It entails the exchange of “favors of access” to public resources among people who have social relationships with each other. These social relationships can be based on membership in a group (such as relatives or co-ethnics), but they might also include loose networks of friends and acquaintances (Ledeneva 1996/7). Given constant shortages in the Soviet economy, blat was used widely by people to exchange anything from repairs to information about new deliveries in a supermarket. Reciprocity based on blat exchange has survived the socialist economy. Women in Russia have been crucial actors in the operation of the second (unofficial) economy under socialism, and hence in blat exchange, and their role has also survived the Soviet economy. Cut off from access to credit and business incentives and discriminated against in the labor market for waged work (Bridger et al. 1996), women rely on habits and networks developed within the second economy to earn a living for their families. It has been argued that women are creating a “non-Western” understanding of entrepreneurship based on their own culture (Bruno 1997: 63). In an environment in which contract laws are de facto useless because of the administrative chaos in Russia, people resort to other methods in order to do business. If big entrepreneurs use protection rackets to enforce contracts, for the small business owner, one’s 24 2 4 Deniz Yükseker word is more important than a contract on paper. Under these conditions, women petty entrepreneurs boast of their trustworthiness in business relations, a trait that they have nurtured through barter and exchange relations in the Soviet period. My argument is that chelnoki and especially the women embark into shuttle trading geared with certain habits and norms about doing business in an informal environment. Thus, when buyers and sellers face each other to engage in market exchange in Laleli, they already have predispositions to do business based on “trust.” Although their understandings of trust have different backgrounds, I argue that the common denominator is a willingness to take risks in a marketplace where they cannot rely on legal regulation – contracts, courts, and so on – but also, where there exists a mutual expectation of profits to be made through exchange. But does such “trust” work in practice? Here, we might recall the shoe store owner quoted above, who said that he would sell merchandise on credit to “Russians”, but not to Turkish citizens, because Russians were honest and trustworthy people. His business principle made sense in 1996 when I talked to him. The Turkish economy was in constant crisis in the 1990s (only to get worse since then). Since manufacturing and wholesaling usually depends on bills of payment with three- to six-month maturity periods, doing business for the domestic market meant susceptibility to exchange rate fluctuations, high inflation rates and the ever-present danger of defaulted payments. Especially in the wake of the devaluation of 1994, many manufacturers and wholesalers in Istanbul found a fresh opportunity in the suitcase trade market to work with a relatively steady cash flow. Hence, it made sense indeed to give credit to Russians but not to Turkish citizens. People operated on güven in Laleli, but that precisely meant that one should not give credit to customers at such a high amount that it would endanger his enterprise. This was the trick of being a “good” entrepreneur in Laleli: taking risks, but not too much. The “bad” entrepreneur was a person 25 2 5 Deniz Yükseker who overstretched the principle of “trust” either by exposing himself to fraud or by cheating others. Beyond this point we hear the stories of the inexperienced migrant entrepreneurs who might be fooled by anything from “feminine guiles” to false promises by “friends” from Siberia. What about the difference between Christians (Slavic traders) and Muslims (Azerbaijanis) in terms of trustworthiness? In fact, I repeatedly heard from Laleli shopkeepers that Azerbaijanis to whom they sold merchandise on open accounts cheated them. Some complained that Azerbaijanis were more likely to take advantage of their good faith than Russians. I am unable to interpret this discrepancy between storeowners’ perceptions towards traders from different regions due to lack of ethnographic evidence. Still, the very existence of this discrepancy lends support to my argument that there was a shared ground between Turkish nationals and Russians when they operated on “trust.” But that common denominator seems to be missing in the interactions between the shopkeepers and Azerbaijanis despite the presence – ironically – of a perception of shared cultural and historical heritage.10 Embedding “Trust” in the Global Economy However, business relations based on “trust” are fragile at a more concrete and general level than the honesty and trustworthiness of individual entrepreneurs or traders from a certain region. The seasonal ups and downs of trade, and the economic downturns in the 10 Having raised the problem that Azerbaijanis are sometimes seen as cheaters, I must say a few words on this issue in order to quell any impression of prejudice on my part. The whole issue of who is “trustworthy” and “honest” among the peoples of the former Soviet Union certainly cannot be understood without considering the subjugated relation of Caucasian, Muslim and Turkic peoples to the Russians. In this unequal relationship, people from the Transcaucasus and Central Asia were tied to the second economy in Russia after the 1970s through the organized smuggling and theft of agricultural produce, not surprisingly, in collusion with Communist party officials (Sterling 1994). Disguised as a condemnation of black marketing under socialism, in the popular imagination, the distrust of the “southerner” was probably combined with ethnic prejudice. On the other hand, the disappointment of some Turkish nationals with Azerbaijanis should be examined within the process of revitalization of cultural links between Turkey and the Turkic republics. Although common historical and linguistic heritage is often hailed, ultimately, citizens of Turkey and Turkic people from the FSU are members of very different nation-states. Here again, the culturally subjugated position of Turkic and Muslim peoples in the USSR comes into play. 26 2 6 Deniz Yükseker region’s national economies might have a bigger impact in turning “trustworthy” business relations sour in Laleli. More broadly, world economic events have a repercussion in the networks of shuttle trade, too. Let me explain these three points through some examples. The season of 1996-97 is a case in point to the impact of seasonal fluctuations in shuttle trade. That year, the Russian government had not paid wages in the public sector for months, thus leading to a contraction in demand for consumer goods. Chelnoki were finding it hard to turn over their working capital. I met traders in Moscow who had been unable to sell off merchandise they had bought on previous trips to Istanbul. For instance, one woman who sold leather coats still had merchandise left over from the winter when I met her at the beginning of the summer. Therefore, she put off her next trip to Istanbul. In the meantime, she sent a message to her supplier in Istanbul through a Turkish friend in Moscow, promising to pay her debt next fall. Back in Laleli during the same time, word was in the air that a chain of bankruptcies had occurred among shopkeepers who relied heavily on lagged payments by the shuttle traders. Rents for shop space were usually in dollars or D-Marks, therefore, if a storeowner did not have steady sales, he would default on his rent payments and quickly go under. But certainly, the litmus test of doing business in an unregulated environment was the economic crisis in Russia in summer 1998. In August, the Russian currency was sharply devaluated, throwing the economy into chaos. When I visited Laleli a year later in 1999, I observed that about one half of the stores had closed down. “For rent” signs were everywhere. Some of the shopkeepers I had met two years before had left the market. Others said their business volume had declined by two thirds. When I went back to Laleli in summer 2001 for more fieldwork, shuttle trading had already started to recover from the low point in 1998 and 1999. The following picture emerged from the accounts of the entrepreneurs I interviewed this time. Chelnoki who had ruble holdings saw their working capital melt 27 2 7 Deniz Yükseker overnight in August 1998, thus preventing them from taking shopping trips abroad for months. In Laleli, suppliers who had large “open accounts” with their Russian customers were hurt the most. Bankruptcies ensued. Those who were less reliant on credit survived 1999 by diversifying their sales to East European customers. Some manufacturers likewise survived by turning to the domestic market or reducing production. Suppliers told me that during the course of the crisis, they had lost many of their regular customers, who either did not pay back debts or simply had to discontinue shuttling. After six months to a year, chelnoki started to return to Laleli. As business started to pick up, new patterns of repeat trading were established. Shuttle traders and suppliers that I interviewed still stressed the importance of doing regular business with the same people. But very interestingly, suppliers said that their current “regular customers” were not the same people as before August 1998. Thus, the renewed opportunity of making money had created a renewed incentive to engage in repeat trading, yet with different people this time. I talked with the shoe store owner again who had said in 1997 that he had more faith in Russians than Turks. He had suffered big losses during the Russian crisis and got cheated by customers and workers alike because of the unregistered and informal nature of his business. But he had survived by downscaling his operations. When I reminded him of his comments on honesty, he said: “I still think that Russians are trustworthy. That is, more trustworthy than Turks. But they are trustworthy only if they are making money by doing business with you.” Hence, what tied a chelnok to a store was the cash flow, as much as the same consideration ties a supplier to a manufacturer. This brings us to the third aspect of the fragility of business relations based on “trust”; namely, the impact of changing conditions in the world economy. We should remember that ultimately, the transnational market of shuttle trade exists within the global economy where prices, fashions, exchange rates, etc. are factors that are beyond the control of shuttle traders and suppliers, individually and as groups of entrepreneurs. If t-shirts are cheaper in Indonesia 28 2 8 Deniz Yükseker and leather coats are cheaper in China, or if women’s clothing is of a better quality at the same prices in Poland, many chelnoki would naturally change their shuttling itinerary in order to take advantage of those opportunities. In fact, suitcase trade from Turkey has been exposed to such centrifugal forces since the second half of the 1990s. The fixed exchange rate policy pursued by the Turkish government, coupled with the impact of the Asian economic crisis in terms of “cheapening” the price of Asian exports constantly ate away the competitiveness of Turkish apparel and leatherwear production. In the folklore of Laleli, the numbers of shuttle traders were decreasing because they were perceived to be sick and tired of “rural” entrepreneurs who cheated them or harassed the female chelnoki. But more likely, shuttle traders were drawn to countries where they could get “better deals.” Moreover, those who never returned to Laleli after buying merchandise on credit could very well be investing that money into buying consumer goods in another country. In fact, in the responses to the survey I conducted among suitcase traders, being cheated or harassed by Turkish suppliers was not a significant complaint. Chelnoki were more concerned about the wage arrears problem in Russia, the declining purchasing power of people, harassment by the mafia in the marketplaces where they sold goods, theft of their goods at the customs warehouse, and so on. In my interviews with female traders, they had a simple answer when I asked what they would do if they were cheated or harassed by a shopkeeper in Laleli: “I would not do business with him again. I would go to another store.” Moreover, the competition within the broader transnational market of shuttle trade was translated into fiercer competition among the suppliers and manufacturers in Laleli. This is an important point to underline, especially given the fact that it is only within the community of Laleli entrepreneurs that we observe a degree of ethnic and regional concentration. Immigrants from the Balkans talked about lending money to each other in times of trouble or sharing a big business deal. But when I asked whether there was a great 29 2 9 Deniz Yükseker deal of solidarity among ethnic Turkish immigrants from Bulgaria in Laleli, the common answer I received was, “there are good people and bad people among us. It all depends.” The following case more clearly demonstrates the instability of co-ethnic solidarity. Kurdish entrepreneurs from the province of Maraş were over-represented in the small-scale garment sector in Istanbul and they commonly boasted of solidarity between apparel manufacturers and Laleli merchants from Maraş. I once witnessed a quarrel between two men from Maraş, who were playing behind each other’s backs to steal customers. The manufacturer had done what shopkeepers dreaded the most: he had sold apparel directly to some shuttle traders, undercutting the prices offered by his Laleli intermediary. This indicates that even when the cultural bases for solidary networks exist, hometown and ethnic ties are as much susceptible to the uncertainties and fierce competition of suitcase trade as business relations among “strangers”. As a corollary, we might conjecture that previously existing social ties may not necessarily be as important as the ones an actor nurtures through trading with foreigners. Laleli is a marketplace characterized by heavy competition. But it is also an unregulated and transnational marketplace. It can be argued that the conditions that would simultaneously encourage and discourage fraud and malfeasance are created by the very competition in the transnational market of shuttle trade. In this environment, the possibility that an actor can move down to the next buyer or seller in the marketplace opens up the opportunity for malfeasance, but the necessity to hold on to that buyer or seller creates and incentive to build friendly and “trusting” business relations. Here, we might overstretch the Hobbesian problem of creating social cohesion out of chaos to restate the point. “[I]t is precisely anarchy which engenders trust…” (Gellner 1988: 143). At this point, the seeming paradox that I had stated earlier, the fact that exchange is embedded in social relations despite the absence of an overarching social structure, is also resolved. Because “trust” and market exchange immersed in friendly (or romantic) relations are not strong principles in shuttle 30 3 0 Deniz Yükseker trade. They are not framed by generalized morality or bounded solidarity. Neither can they be enforced by virtue of membership in a community. But “trust” and friendship are nurtured, precisely because they help facilitate market exchange in a highly competitive and “noisy” transnational marketplace where there is a steady cash flow. In the nodal locations of the shuttle trade network, “trust” is thus “created intentionally” through personal interaction and repetitive exchange among strangers (Lorenz 1988: 209) who are not tied to each other through ethnicity, kinship or nationality. Trust as a Temporally Changing Principle In the above account of doing business through “trust” in Laleli, there is an implicit temporal element that needs to be brought out in order to underline the embeddedness of social relations underlying market exchange in a broader, more specifically, global economic structure. It is my argument that nurturing “trust” became important in this transnational marketplace by the mid-1990s, when competition became fierce. In the first years of its operation, making money was easier for both sides. There were few suppliers and they felt that anything they sold would be bought by the shuttle traders. In turn, suitcase traders had less competition back at home, meaning that anything they offered for sale would be picked up by the consumption hungry public. Stories about entire batches of defective goods and shopkeepers running away with down payments belong to the first half of the past decade. But once suppliers perceived that they were not alone in this game of profit making – not alone in Laleli, but also not alone in the transnational networks woven by the chelnoki – emphasis was laid on honesty, trustworthiness, offering good quality, building a regular clientele, and so on. Hence, stories about honesty and trust refer to the second half of the 1990s. But simultaneously, chelnoki were pressed at home to be more competitive against other shuttle traders in terms of popular apparel models, prices, faked Western brand names, etc. Thus they started shuttling across a much broader geography, making it less costly for 31 3 1 Deniz Yükseker them to cheat on Turkish suppliers. Hence, stories about trust and distrust get entangled also in the second half of the decade. Once we draw a temporal picture of “trust” in business relations in this way, it becomes clear that, ultimately, the “social embeddedness” of market exchange is itself embedded in the framework of the global economy. The usefulness of our Braudelian framework also becomes obvious at this point. In order to clarify this argument, I want to turn to the field of the new economic sociology. Spearheaded by Mark Granovetter (1985), the new economic sociology’s main thrust is against the simplistic vision of economic life presented by neoclassical theory, which presumes atomization of actors as a precondition for market exchange. What discourages malfeasance and fraud in such a market, according to Granovetter, is neither institutional arrangements nor generalized morality, but rather, the generation of trust within “concrete personal relations and structures (or “networks”) of such relations” (ibid.: 490). The embeddedness approach has been widely used in analyzing how exchange in various sorts of markets, from industrial districts to subcontracting arrangements, from ethnic economies to the informal sector, are immersed in social networks. In Granovetter’s scheme, because trust is generated through personal relations, it is also susceptible to be abused by either side for the same reason. Sociologists of immigration led by Portes have a somewhat different take on this issue. If trust is generated within the framework of overarching solidarity in a group, it becomes easier to enforce it. Though in this case, the “down side” of enforceable trust (as a form of social capital) is that there are obligations to the community as much as resources to be tapped from it, which may in the end stifle potential investments and profits (Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993; Portes and Landolt 2000). As the discussion in this article sought to demonstrate, exchange in a transnational marketplace conforms to neither of these visions, although somewhat closer to the previous. 32 3 2 Deniz Yükseker What is missing in the new economic sociology is that analyses of business networks and social networks in which economic action is immersed are not framed in the structure of the world economy. Giovanni Arrighi (2001) has recently underscored this point when he discusses the “double silence” of the new economic sociology on capitalism and Braudel. The field of new economic sociology is so concerned with “micro” processes such as network forms of business organizations, social networks, and so on, that it fails to have a “macro”, structural and long-term perspective a la Braudel. Telling, in this respect, is Arrighi’s observation that in The Handbook of Economic Sociology (Smelser and Swedberg 1994), the word capitalism as a “minimally useful signifier” is used on only 14 pages and Braudel is referenced on only 7, in a total of 797 pages (Arrighi 2001: 109, 110). Conclusion From our perspective in this article, the crucial issue is the interaction between Braudel’s market economy and capitalism. We are faced with a double problem: on the one hand, the actors in the transnational marketplace of Laleli lacked an overarching social structure or a legal framework within which they could enforce “honest” business. On the other hand, even when they fashioned an eclectic notion of “trust” in the absence of formal and/or social regulation, ultimately, business relations were at the mercy of economic forces beyond their control. As a corollary to this, we may argue that even if shuttle trade were taking place through networks of ethnic trade diasporas, it would still be prone to falter in the face of the dictates of the global market. I can express this argument in the conceptual terminology I developed at the outset. The networks of shuttle trade constitute a transnational informal economy, which I have located at the level of the Braudelian market. It is characterized by high competition, relatively small profits, but very significantly, also by the absence of upholding of transactions by states; hence the weakness of statal regulation. As such, it is diametrically 33 3 3 Deniz Yükseker opposed to the top level of the economy, the anti-market, if not completely independent of it. Although the creation of economic spaces by receding state regulation has created a breeding ground for the transnational market economy, the market is affected by developments occurring at the uppermost level. Changing state policies, world market prices, regional economic crises created by global forces all have an impact upon the working of the Braudelian market. In the case of shuttle trade between Turkey and the former Soviet Union, the vagaries of the global economy are reflected in the everyday transactions of buyers and sellers in a marketplace, both creating incentives for, and undercutting the necessary conditions of, the engendering of social ties and “trust” that underlie market exchange. REFERENCES Appadurai, A. 1996. Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Arrighi, A. 2001. “The New Economic Sociology and its Double Silence on Capitalism and Braudel,” Review, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 107-123. Arrighi, G. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century. London: Verso. Attwood, L. 1996. “The Post-Soviet Women in the Move to the Market: A Return to Domesticity and Dependence?” in R. Marsh, ed. Women in Russia and Ukraine. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press. 34 3 4 Deniz Yükseker Basch, L., N. Glick Schiller and C. Blanc Szanton. 1994. Nations Unbound. Transnational Projects Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Langhorne, Pa.: Gordon and Breach. Blacher, P. 1996. “Les ‘Shop-Turisty’ de Tsargrad ou les Nouveaux Russophones d’Istanbul,” Turcica, vol.28, pp.11-50. Braudel, F. 1982. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century, vol.2. New York: Harper and Row. Bridger, S., R. Kay and K. Pinnick. 1996. No More Heroines? Russia, Women and the Market. London and New York: Routledge. Bruno, M. 1997. “Women and the Culture of Entrepreneurship” in M. Buckley, ed. PostSoviet Women: From the Baltic to Central Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Buckley, M. ed. 1997. Post-Soviet Women: From the Baltic to Central Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Carnoy, M. 1993. “Multinationals in a Changing World Economy: Whither the NationState?” in M. Carnoy et.al., eds. The New Global Economy in the Information Age. Reflections on Our Changing World. University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press. Castells, M. 1996. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Vol.1. The Rise of the Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Curtin, P. 1984. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Diouf, M. 2000. “The Senegalese Murid Trade Diaspora and the Making of a Vernacular Cosmopolitanism,” Public Culture, vol. 12, no.3, pp. 679-702. DIE (State Institute of Statistics). 1996. Yearbook of Foreign Trade. Ankara: DİE DPT (State Planning Organization). 2001. http://www.dpt.gov.tr Freeman, C. 2000. High Tech and High Heels in the Global Economy. Women, Work, and Pink-Collar Identities in the Caribbean. Durham: Duke University Press. Gambetta, D., ed. 1988. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. New York: Blackwell. Geertz, C. 1992. “The Bazaar Economy: Information and Search in Peasant Marketing” in M. Granovetter and R. Swedberg, eds. The Sociology of Economic Life. Boulder, CO.: Westview Press. Geertz, C. 1963. Peddlers and Princes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gellner, E. 1988. “Trust, Cohesion, and the Social Order” in D. Gambetta, ed. Trust. Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Glick-Schiller, N., L. Basch and C. Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration,” in N. Glick-Schiller, L. Basch and C. Szanton-Blanc, eds. Toward a Transnational Perspective on Migration. New York: New York Academy of Sciences. 35 3 5 Deniz Yükseker Granovetter, M. 1985. “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness,” American Journal of Sociology, no.91, pp. 481-510. Guarnizo, L.E. and Smith, M.P. 1998. “The Locations of Transnationalism” in M.P. Smith and L.E. Guarnizo, eds.Transnationalism from Below, Comparative Urban and Community Research, vol.6. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. Gültekin, B. and Mumcu, A. 1996. “Black Sea Economic Cooperation” in V. Mastny and C. Nation, eds. Turkey between East and West. New Challenges for a Rising Power. Boulder, Co.:Westview Press. Hannerz, U. 1996. Transnational Connections. Culture, People, Places. London and New York: Routledge. Hart, K. 1988. “Kinship, Contract, and Trust: The Economic Organization of Migrants in an African City Slum” in D. Gambetta, ed. Trust. Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Hirst, P. and Thompson, G. 1996. Globalization in Question. The International Economy and the Possibilities of Governance. Cambridge, U.K. Unity Press. ITAR-TASS. 1997. “Press Conference with Yevgeny Yasin, Minister of the Economy and Anatoly Kruglov, Chair, State Customs Committee of the Russian Federation,” Moscow: Wire Service. İTO. 1995. Sınır ve Bavul Ticareti Toplantısı [Proceedings of the Border and Suitcase Trade Meeting], Istanbul: İstanbul Ticaret Odasi. Kaminski, B., ed. 1996. Economic Transition in Russia and the New States of Euroasia. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. Karpat, K. 1985. Ottoman Population 1830-1914. Demographic and Social Characteristics. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Kyle, D. 2000. Transnational Peasants: Migrations, Networks, and Ethnicity in Andean Ecuador.. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Lash, S. and Urry, J. 1994. Economies of Signs and Space. London: Sage. Ledeneva, A. 1996/7. “Blat Exchange: Between Gift and Commodity,” Cambridge Anthropology, vol. 19, no.3, pp.43-66. Lorenz, E. 1988. “Neither Friends nor Strangers: Informal Networks of Subcontracting in French Industry” in D. Gambetta, ed. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. New York: Blackwell. MacGaffey, J. and R. Bazenguissa-Ganga. 2000. Congo-Paris. Transnational Traders on the Margins of the Law. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. MacGaffey, J. 1991. The Real Economy of Zaire. The Contribution of Smuggling and Other Unofficial Activities to National Wealth. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Marques, M.M., R. Santos and F. Araujo. 2001. “Ariadne’s Thread: Cape Verdean Women in Transnational Webs,” Global Networks, vol. 1, no.3, pp. 283-306. OECD 1997. OECD Economic Surveys: Russian Federation 1997-1998. Paris: Organization of Economic Co-Operation and Development. 36 3 6 Deniz Yükseker Özveren, E. 1997. “A Framework for the Study of the Black Sea World, 1789-1915,” Review, vol.20, no.1, pp.77-113. Portes, A. 1995. “Economic Sociology and the Sociology of Immigration: A Conceptual Overview” in A. Portes, ed. The Economic Sociology of Immigration. Essays on Networks, Ethnicity and Entrepreneurship. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Portes, A. 1994. “The Informal Economy and its Paradoxes” in N.J. Smelser and R. Swedberg, eds. The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Portes, A. and P. Landolt. 2000. “Social Capital: Promise and Pitfalls of its Role in Development,” Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 32, pp. 529-547. Portes, A. Guarnizo, L.E. and P. Landolt. 1999. “Introduction: Pitfalls and Promise of an Emergent Research Field,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, special issue, vol.22, no.2, pp.217-237. Portes, A. and J. Sensenbrenner. 1993. “Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action,” American Journal of Sociology, vol.98, no.6, pp.1320-50. Rzhanitsyna, L. 1995. “Women’s Attitudes Toward Economic Reforms and the Market Economy” in V. Koval, ed. Women in Contemporary Russia, Providence: Berghahn Books. Sassen, S. 1998. Globalization and its Discontents. Essays on the New Mobility of People and Money. New York: The New Press. Sassen, S. 1991. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Schroeder, G. 1996. “Economic Transformation in the Post-Soviet Republics: An Overview” in B. Kaminski, ed. Economic Transition in Russia and the New States of Euroasia. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. Shami, S. 2000. “Prehistories of Globalization: Circassian Identity in Motion,” Public Culture, vol. 12, no.1, pp.177-204. Shami, S. 1998. “Ciscassion Encounters: The Self as Other and the Production of the Homeland in the North Caucasus,” Development and Change, vol. 29, no.4. Smelser, N.J. and R. Swedberg, eds. 1994. The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sterling, C. 1994. Thieves’ World. The Threat of the New Global Network of Organized Crime. New York: Simon and Shuster. Tekeli, İ. 1990. “Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’ndan Günümüze Nüfusun Zorunlu Yer Değiştirmesi ve İskan Sorunu” [The Forced Displacement of Populations and Resettlement Question since the Ottoman Empire], Toplum ve Bilim, no.50, Summer, pp.49-71. Yenal, H.D. 2000. “Weaving a Market: The Informal Economy and Gender in a Transnational Trade Network between Turkey and the Former Soviet Union,” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Binghamton University. 37 3 7 Deniz Yükseker Yükseker, D. forthcoming. “On the Embeddedness of Economic Action: Gendered Trading in a Transnational Marketplace in Istanbul,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, Special Issue on Migration and the Subversion of Gender. Wallerstein, I. 1991. Unthinking Social Science. The Limits of Nineteenth Century Paradigms. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press. Womack, B. and Zhao, G. 1994. “The Many World of China’s Provinces. Foreign Trade and Diversification” in D.S.G. Goodman, G. Segal eds. 1994. China Deconstructs. New York: Routledge. 38 3 8