Water Infrastructure Options Paper

advertisement

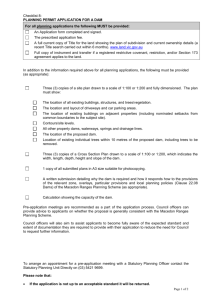

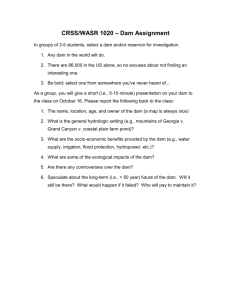

© Commonwealth of Australia 2014 Ownership of intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence, save for content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. Cataloguing data This publication (and any material sourced from it) should be attributed as Water Infrastructure Options Paper CC BY 3.0. ISBN No: 9781760030834 (online) ISBN No: 9781760030841 (printed) Internet Water Infrastructure Options Paper is available at agriculture.gov.au. Contact Australian Government Department of Agriculture Postal address GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Switchboard +61 2 6272 3933 Facsimile +61 2 6272 2001 Email info@agriculture.gov.au Web agriculture.gov.au Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of this document should be sent to copyright@agriculture.gov.au. The Australian Government acting through the Department of Agriculture, has exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the Department of Agriculture its employees and advisers disclaim all liability, including liability for negligence, for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any person as a result of accessing, using or relying upon any of the information or data in this publication to the maximum extent permitted by law. Contents Introduction 1 Role for the Commonwealth in water infrastructure development 2 Potential projects for possible Commonwealth involvement 3 Options to accelerate development 9 Appendix A: Prime Minister’s Guidelines to the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 14 Appendix B: Summary of potential projects that have been identified for possible Commonwealth involvement 16 Appendix C: Projects identified by state and territory governments and others for consideration 27 Appendix D: Indicative water infrastructure project development phases used by the Ministerial Working Group (provided by the Department of Agriculture) 30 Appendix E: Consideration of funding and financing models for water infrastructure 32 Published: 29 October 2014 Photo credits Cover – main image: Burrinjuck Dam (2009) Copyright © Murray Darling Basin Authority, Photographer, Irene Dowdy Introduction The Government made an election commitment to start the detailed planning necessary to build new dams – to secure the nation’s water supplies and deliver strong economic benefits for Australia, while protecting the environment. This options paper will assist to progress water resource development and cement the commitment to infrastructure and getting our nation moving efficiently and competitively. The paper has been developed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Prime Minister to identify how investment in water infrastructure could be accelerated, priorities for investment in dams, opportunities in groundwater, and how these approaches will improve the management of Australia’s water resources, taking into account economic, social and environmental considerations (Appendix A). The options paper has been developed so the government can consider its outcomes as part of the White Papers on Developing Northern Australia and Agricultural Competitiveness. Water resources development can encourage regional development and contribute to regional and national economic and social benefits. Investment in water infrastructure can raise productivity and economic activity, meeting critical needs for all Australians, including safe drinking water, sanitation and provide for flood mitigation. Water infrastructure also supports expanding industries such as mining and irrigated agriculture, particularly in rural and regional areas. Given the nature of our dry continent, it is critical infrastructure. Infrastructure development is complex, and water infrastructure has its own unique challenges. Development has long lead-times, requires substantial capital and maintenance for many years due to its life expectancy. Water infrastructure must be built to the right scale, at the right time, with sufficient demand and with the right supporting infrastructure if full benefits of the investment are to be realised and undesirable costs avoided. Water infrastructure also often requires significant supporting infrastructure, such as roads. Early planning is necessary if major infrastructure proposals are to be properly considered to meet future demands. 1 Role for the Commonwealth in water infrastructure development The Commonwealth can play an effective leadership role in facilitating the development of major water infrastructure projects in several key areas, including by: supporting future planning; continuing to promote national water management reform; providing or assisting with scientific and economic advice and analysis; efficiently administering national environmental legislation; and, in some cases where there is a clear national case for assistance, providing direct financial investment for construction. Commonwealth involvement in water infrastructure development should be directed to activities that are in the national interest, deliver net economic and social benefits and broader public benefits. It is also expected that given the primary state and territory responsibility for water resources there must be strong state or territory government support for projects. To determine whether a water infrastructure project warrants Commonwealth involvement principles addressing the above considerations should be applied. Projects need to be nationally significant and in the national interest. There must be strong state or territory government support with capital contribution and involvement of the private sector and where appropriate local government. The investment will provide the highest net benefit of all options available to increase access to water, taking into account economic, social and environmental impacts. Projects should address a market failure which cannot be addressed by proponents, state and territory governments or other stakeholders and limits a project of national significance from being delivered. Projects should align with the Governments broader infrastructure agenda to promote economic growth and productivity or provides a demonstrable public benefit and addresses a community need. Projects should align with the National Water Initiative principles including appropriate cost recovery and where full cost recovery is not deemed feasible, any subsidies are fully transparent to the community. If providing capital, a consistent, robust analysis of costs and benefits and assessment is undertaken. These principles have been based on transport infrastructure investment principles and the approaches contained in the National Water Initiative. 2 Potential projects for possible Commonwealth involvement In preparing this paper, consultation was undertaken with state and territory jurisdictions through relevant ministers and agencies as provision of water infrastructure is predominantly a state or territory government responsibility. All governments were asked to provide a list of priority projects for consideration; explain their processes for determining priority projects; identify any barriers to accelerate investment in water infrastructure and consider the role water infrastructure plays in improving the management of water resources. With relatively few exceptions, the states and territories are not actively pursuing significant, large scale water infrastructure development at present. A total of 63 projects have been identified by the states, territories and others for further consideration. The overwhelming majority of these are similar in preliminary concepts or in the very early stages of assessing feasibility. Only a small number have a reasonable prospect of being construction ready within the next year or two. Most are at least several years away from construction. The analysis of projects took account of the principles identified above. The projects have been categorised on the basis of when potential investment decisions may be necessary, the nature of activities for which assistance is being requested, such as investigations of feasibility or a contribution to construction costs, and whether more information is needed to enable an assessment of the project to be made. Further information on all projects would be needed before decisions regarding possible Commonwealth involvement could be recommended. In particular, although projects can be ranked in terms of stage of development, there is insufficient information at present to confidently rank projects in terms of net benefit. The categories of projects are: 1. Project already funded with existing Commonwealth assistance 2. Likely to be sufficiently developed to allow consideration of possible capital investment within the next 12 months 3. Could warrant future consideration of possible capital investment, but less advanced in stage of development 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design 5. Likely to occur without direct Commonwealth involvement 6. More information is required from state and territory government to inform categorisation It should be noted that while a number of projects may eventually be developed to a point where the need Commonwealth assistance could be determined, a commitment to fund either further studies or to invest directly in construction should be subject to receipt of more detailed proposals from the states and the Northern Territory and rigorous analysis. Many of the projects may be capable of proceeding without the need for any Commonwealth Government assistance for construction. Also, before any commitment to a project is made, particularly for investing directly in construction, a comprehensive analysis of cost effectiveness and feasibility should be undertaken, noting that evaluation of this analysis by Infrastructure Australia is required for project proposals involving at least $100 million of Australian Government funding. With very few projects being close to construction ready, consideration 3 could be given encouraging the states and territories to accelerate the development of projects through possible Commonwealth assistance for investigations and feasibility studies. Based on the outcomes of consultation with state and territory governments, 31 projects have been identified as having the potential for Commonwealth involvement. This involvement would not necessarily be in the form of financial assistance for construction — as noted above, Commonwealth assistance for construction costs would need to be determined rigorously following consideration of detailed business cases from state governments and in light of the Government’s broader fiscal objectives. Map 1 shows the potential project locations and they are outlined below. 1. Project already funded with existing Commonwealth assistance a. The Commonwealth has already provided a financial commitment of $18 million to progress the augmentation of Chaffey Dam in New South Wales, which has commenced construction in October 2014. b. A sum of $180 million has been committed to improve the operation and efficiency of the Menindee Lakes. Detailed project planning, stakeholder consultation and design work for the agreed scope of works is currently underway. c. The Commonwealth provided $545 771 for a feasibility study for the Nimmitabel Lake Wallace project. The project has been identified by the New South Wales Government as a high priority project for funding under their Water Security for Regions Program. d. The Great Artesian Basin Sustainability Initiative will be extended for a further three years in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia with the Commonwealth providing $15.9 million. 2. Likely to be sufficiently developed to allow consideration of possible capital investment within the next 12 months a. Gippsland: Macalister Irrigation District / Southern Pipeline, Victoria b. Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Southern Highlands c. Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Scottsdale d. Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Circular Head e. Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Swan Valley f. 4 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: North Esk Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 3. Could warrant future consideration of possible capital investment, but less advanced in stage of development a. Gippsland: Lindenow Valley Water Security Project, Victoria b. Emu Swamp Dam – Severn River, Stanthorpe, Queensland c. Nathan Dam, Dawson River, Queensland d. Wellington Dam Revival Project, Western Australia 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design a. Apsley Dam – Walcha, New South Wales b. Lostock Dam enlargement – Hunter Valley, New South Wales c. Mole River Dam, New South Wales d. Needles Gap, New South Wales e. Burdekin Falls Dam (including Water for Bowen), Queensland f. Connors River Dam – Sarina, Queensland g. Fitzroy Agricultural Corridor – construction of Rookwood Weir and raising Eden Bann Weir h. Mitchell River System, Far North Queensland i. North Queensland Irrigated Agriculture Strategy: Flinders-Gilbert, large scale infrastructure proposals (e.g. IFED) and on-farm developments j. Nullinga Dam – Cairns, Queensland k. Urannah Dam – Collinsville, Queensland l. Ord Irrigation Stage III (water infrastructure components), Northern Territory and Western Australia m. Pilbara and/or Kimberley irrigated water pipeline system, Western Australia n. Expanded Horticulture Production on the Northern Adelaide Plains - Waste Water Re-use, South Australia o. Intensive Livestock and Horticulture Expansion – Northern Dams Upgrade – Clare Valley, South Australia 5 Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group p. Exploring off-stream storage opportunities to increase water availability for agricultural development, Northern Territory q. Upper Adelaide River Dam / off stream storage, Northern Territory A summary of each of the 31 projects listed above is at Appendix B. The remaining 32 projects have been categorised as likely to occur without direct Commonwealth involvement or more information is required from state and territory governments to inform categorisation (Appendix C). A number of small scale flood mitigation projects were suggested by the states. On the basis of scale and capacity for costs to be recovered from future developments these were not considered as requiring Commonwealth involvement. However, both Queensland and New South Wales are currently investigating flood mitigation options in south east Queensland and the Hawkesbury-Nepean area respectively, and may come forward with related project priorities in the next year or two. Managed aquifer recharge was also identified by some states, including Western Australia and the Northern Territory as worthy of further investigation, particularly in Northern Australia. 6 Map 1: Potential water infrastructure projects for possible Commonwealth involvement 7 8 Options to accelerate development Leading future planning The Commonwealth has a role in identifying and assessing infrastructure that is nationally significant. Infrastructure Australia is responsible for identifying current and future infrastructure assets of national significance as part of its infrastructure audit currently underway. Infrastructure Australia is also responsible for evaluating infrastructure project proposals seeking at least $100 million of Commonwealth funding. Infrastructure Australia is developing a 15 year infrastructure plan covering water, transport, energy and communications, to be completed by the end of this year. Infrastructure Australia is also conducting an audit of infrastructure needs for Northern Australia. Project development Where a project is in the development pipeline it can be described in four stages: 1. assessing demand and general feasibility, including location 2. assessing economic feasibility through benefit cost analysis 3. gaining approvals and assessments 4. seeking finance for capital and establishing cost recovery for ongoing maintenance. Appendix D provides further information on the stages of development for water infrastructure. To fast track investment in water infrastructure the Commonwealth would mainly be involved in stages 1 and 4 of project development. Assessing economic feasibility is predominately the proponent’s role, noting that a lack of a well developed economic case is a major barrier to development. Seeking capital is also predominantly the proponent’s role. Stage 1: assessing demand and general feasibility, including location (early scoping) In this stage, proponents undertake preliminary scoping; establishing the demand for water, undertake water planning considerations, assess water resources and infrastructure options and fund preliminary studies of these. New infrastructure must address a forecast water supply requirement or provide a substantiated opportunity for economic growth. 9 Options to accelerate investment could include funding pre-commercial pre-feasibility assessments, such as for groundwater, opportunities in hydro-generation or providing base-line information assessing water availability and sustainable extraction rates. Some work would draw on the expertise of agencies such as CSIRO and Geoscience Australia. These agencies already provide a level of assistance, but special projects could also be funded. Funding could be through development of a modest program that would provide matching funding to incentivise state and territory governments to focus on ensuring the feasibility studies, economic analyses and more detailed assessment and design is undertaken for projects in the early stages of development. Stage 2: Assessing feasibility through benefit cost analysis (assessing feasibility) In this stage, proponents have primary responsibility for determining the economic viability and complete benefit cost analysis. Potential Commonwealth involvement in this area is limited. Any possible assistance can be guided by the Commonwealth’s response to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into public infrastructure, including to the recommendation that all public infrastructure investment proposals above $50 million are subject to a rigorous cost–benefit analysis. The Commonwealth is considering the recommendations made by the Productivity Commission and will formally respond to the inquiry in late 2014. The current government support for the analysis of base line information assists proponents and Infrastructure Australia, or other experts, to undertake analysis. Stage 3: Gaining approvals and assessments (decision to proceed) During this stage the Commonwealth plays a role in undertaking environmental approvals and assessments in relation to matters of national environmental significance which may be impacted by water infrastructure developments. Broader Commonwealth legislation and policies, particularly in the areas of competition policy, investment and taxation may also affect delivery of water infrastructure and influence investment decisions made by other governments and the private sector. The Commonwealth’s implementation of a one stop shop for environmental approvals will contribute to fast tracking approvals. There could also be opportunities for broader policies through existing Commonwealth processes including a review of environmental offset policies, the White Papers on Developing Northern Australia and Agricultural Competitiveness, the COAG regulation agenda, the Commonwealth’s response to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into public infrastructure, and the Productivity Commission’s report into major project assessment processes. Stage 4: seeking finance for capital and establishing cost recovery for ongoing maintenance (ready to go) This stage includes finalising designs and securing investment. Capital investment is a key barrier given the expense of water infrastructure. 10 Funding for capital (and pre-commercial feasibility studies) could possibly be through some Commonwealth programmes but the quantum of these funds is likely to be limited, particularly for capital. Potential projects that include a hydroelectricity component (e.g. Nullinga Dam, Urannah Dam, Apsley Dam) may be eligible for funding through new or existing energy initiatives. Capital funding for some smaller projects may be eligible through the National Stronger Regions Fund, which is a competitive grants programme available to local governments and not-for- profit organisations. It may be appropriate to develop a new type of funding model in the style of the New Zealand Irrigation Acceleration Fund or an augmentation of the existing Australian Government Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program. Commencing in 2011, the New Zealand Irrigation Acceleration Fund has been allocated $35 million over five years and includes three components to target the delivery of investment ready rural infrastructure proposals: 1) regional rural water infrastructure, 2) strategic water management studies, and 3) community irrigation schemes. Additionally, New Zealand Crown Irrigation Investments Ltd acts on behalf of the New Zealand Government as a bridging investor for regional water infrastructure developments by making targeted investments into schemes, alongside other partners, that would not otherwise be developed. Schemes have to be technically feasible, have appropriate allocation of risks, sound management and governance (including arrangements that do not create competition policy issues), have consents in place, be of an optimal size and be commercially viable in the mediumterm. The New Zealand Government has signalled that it plans to invest up to $400 million, with $80 million provided in the 2013 budget and $40 million in the 2014 budget. The current white paper processes for Northern Australia and agricultural competitiveness will provide an opportunity to consider funding for investing in priority water infrastructure developments relative to other infrastructure opportunities. It would be expected in all cases the relevant state or territory government, and/or project proponent, contributes funding to the projects. Given the respective responsibilities of the state and territories and the potential flow of private benefits it would not be expected that the Commonwealth would fund more than 50 per cent of a proposal or ever exceed the state or territory contribution where a private sector capital contribution is obtained. Private sector participation, including foreign investors, can act as a driver in water infrastructure development. It encourages emphasis on a sound economic and financial case for the proposed development, as investors will require a return on investment. This should ensure that demand and willingness to pay are investigated, and that a user pays model is implemented. Foreign investment has been welcomed for Ord Stage II. In other cases private sector investment can be in partnership with government to deliver essential services, where private sector involvement can bring about efficiencies in the delivery of water infrastructure (examples include urban water development or flood mitigation where costs can be fully recovered). The recent report by the Productivity Commission inquiry into public infrastructure noted the efficiencies that private sector involvement can bring. Previous Tasmanian Irrigation projects had a public private partnership and have been successfully implemented. There is also potential to attract mining investment to allow the further development of mining resources. Financing models In addition to Commonwealth direct funding for capital, there are a range of alternative mechanisms to raise money, such as charges on users or beneficiaries of the infrastructure. Additional alternative financing mechanisms available to governments include concessional loans, government guarantees, equity injections and phased grants (availability payments). The use of alternative financing mechanisms can also remove some impediments to private sector financing, providing governments with greater flexibility to reduce budget outlays and improve opportunities to share risk with private sector investors. It is important that private sector co-investment in water infrastructure does not come at the expense of transferring unacceptable risk to governments. It should only be undertaken following a careful case-by-case analysis of the attribution of benefits and costs and risks. The ability to attract private investment in water infrastructure projects or implement alternative financing arrangements will be limited if a project is not economically viable or if it does not align to the guiding principles. 11 Options relating to financing include: Continue to promote and reinforce the commitment to asset recycling with state and territory governments as it provides an extra incentive to partner with the Commonwealth and private investors. The Commonwealth could further explore opportunities to facilitate private sector-led development of future water infrastructure projects, particularly in the agricultural and resources sectors. There are substantial benefits for these sectors developing projects that are built for a specific purpose, particularly where they alleviate supply pressures on existing water infrastructure assets. Most water infrastructure delivers multiple benefits such as domestic and urban water supplies, agriculture irrigated or mining water, flood mitigation and potentially electricity, so partnerships are most likely. Further work beyond the recent Productivity Commission inquiry into public infrastructure is likely to be required to identify those mechanisms that can be successfully applied to water infrastructure without transferring an unacceptable risk. This is particularly important for water infrastructure developed for agricultural purposes, which typically involve a high up front capital cost and generate economic returns over many decades into the future. The Treasury, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development and Infrastructure Australia have expertise in these areas and could be supported by portfolios that are related to major users of water such as agriculture and mining. It should be noted that in the current fiscal environment, the Commonwealth cannot be expected to be a guarantor for all large projects proposed by the states and territories. Appendix E provides further information on alternative funding models. 12 13 Appendix A: Prime Minister’s Guidelines to the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group The members of the Ministerial Working Group include: Minister for Agriculture, the Hon. Barnaby Joyce MP, Chair Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon. Warren Truss MP Minister for the Environment, the Hon. Greg Hunt MP Assistant Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development, the Hon. Jamie Briggs MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for the Environment, Senator the Hon. Simon Birmingham. The ministerial working group will: 14 identify how investment in water infrastructure, such as dams, could be accelerated, including methods for assessing feasibility and cost benefit analysis of particular proposals, the role of Infrastructure Australia, and financing identify priorities for investment in new or existing dams, including the merit of proposals already well-developed and the productivity and/or economic benefits of new or existing dams outline how proposed approaches will improve the management of Australia’s water resources to support economic development, flood mitigation and respond to community and industry needs consider opportunities for ground water storage (aquifers), water reuse and water efficiency to ensure investment in dams occurs where it is the most suitable solution take account of economic, social and environmental considerations, including consistency with National Water Initiative principles. 15 Appendix B: Summary of potential projects that have been identified for possible Commonwealth involvement The 31 projects have been identified through consultation with the state and territory governments and from the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group. 1. Project already funded with existing Commonwealth assistance # Project Name State Description of Project 1 Chaffey Dam (MDB) NSW Stage of development: Construction Raising dam wall, from 62 GL to 100 GL, modifying related infrastructure, and relocating/realigning some roads, bridges and recreational facilities. It will secure future water needs for communities and Peel Valley irrigators, and improve ability to withstand extreme floods. Project agreement signed. Contract for construction has been awarded to John Holland. Construction commenced in October 2014 and anticipated completion is June 2016. Funding secured, including Commonwealth investment of $18.145 million, New South Wales Government investment of $9.668 million and Tamworth Regional council investment of $3.968 million (total $31.781 million). Proposed dam would be located in the Murray–Darling Basin. Any water use associated with the new infrastructure would need to comply with long term sustainable diversion limits (SDL) described in Schedule 2 of the Basin Plan. If the dam were to create new entitlements in a catchment that already uses its full SDL these would need to be offset elsewhere in the catchment. Dam design would need to meet environmental objectives and impacts on downstream flows would need to be considered by the state. The NSW Government has indicated the potential for further works to Chaffey Dam to increase storage capacity to 200 GL (correspondence from Minister Humphries, 16 July 2014). 2 Menindee Lakes NSW Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) New regulators between lakes, an outlet regulator at Lake Menindee and the Darling Anabranch and drainage channels to access dead storage. It will reduce large evaporative losses and contribute to the Murray Darling Basin Plan. The NSW government is currently undertaking detailed project planning, stakeholder consultation and design work for the agreed scope of work. The Commonwealth provided $800 000 to deliver this preliminary assessment work. The Commonwealth has approved $180 million to assess the feasibility of the project and undertake infrastructure works if necessary (to end of 2018-19 financial year). 16 1. Project already funded with existing Commonwealth assistance # Project Name State Description of Project 3 Nimmitabel Lake Wallace NSW Stage of development: Seeking finance for capital and establishing cost recovery for ongoing maintenance (ready to go) Construction of a new dam to increase water security for the village of Nimmitabel, New South Wales. A 2010 feasibility study (led by the Nimmitabel Advancement Group with financial support from the Commonwealth) identified a 200 ML dam on Pigring Creek as a feasible option to reduce the impact of drought and secure Nimmitabel's water supply. Cooma Monaro Shire Council accepted the recommendations of the feasibility study and has committed to construct a dam, to be known as Lake Wallace. Cooma Monaro Shire Council has completed pre-construction activities such as completion of the detailed design and environmental assessments required for planning and Commonwealth environmental approval was granted on 30 June 2014. The Commonwealth contributed $545,771 financial support for the feasibility study and pre-construction activities. The project has been identified by New South Wales Deputy Premier, the Hon. Andrew Stoner MP as a high priority project for funding, subject to final business case approval, under the New South Wales Government’s Water Security for Regions program. $5.3 million has been committed by the New South Wales Government to progress the project. Additional Commonwealth assistance has not been requested. 4 Great Artesian Basin Sustainability Initiative Multi (NSW, QLD, SA) The programme replaces old bores and pipe networks legally operating in an uncontrolled state with controlled bores and efficient watering systems which generates benefits to water users and the environment. The estimated cost of completing the programme is in the order of $199 million across the jurisdictions of New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia. The programme commenced in 1999 and ended on 30 June 2014. The Commonwealth announced on 16 October 2014 it will provide $15.9 million to extend the initiative for a further 3 years. The Commonwealth will work with the New South Wales, South Australian and Queensland Governments on their provision of matched funding. The Commonwealth will also work with the relevant state governments and the Great Artesian Basin Coordinating Committee to develop a new strategic management plan for the basin. Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 17 2. Likely to be sufficiently developed to allow consideration of possible capital investment within the next 12 months # Project Name State Description of Project 5 Gippsland: Macalister Irrigation District / Southern Pipeline – Sale - Maffra VIC Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) Conversion of 85 km open channel to pipeline to increase agricultural production and generate environmental benefits (reduced nutrient flows into local waterways and the Gippsland Lakes). Business case prepared and pipeline design is underway. Expected to be construction ready late 2015. Estimated cost is $80 million. 6 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Southern Highlands TAS Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) 6500 ML dam and 49.6 km pipeline. For irrigation for cropping, grazing and potential new dairy conversions, and supplying reliable drinking water for the community. Business case being approved by Tasmanian Government. Expected to commence construction from March 2015-March 2016. Estimated total capital cost is $28.5 million. Estimated Commonwealth requested contribution is $19.8 million. 7 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Scottsdale TAS Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) 9300 ML dam on Camden Rivulet to deliver 8600 ML a year for dairying, cropping, vegetable production and some livestock finishing, with a 2000 KW mini-hydro power station. Business case to be finalised June 2014. Construction estimated from March 2015-September 2016. Estimated total capital cost is $46 million. Estimated Commonwealth requested contribution is $31.9 million. 8 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Circular Head TAS Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) 15 000 ML off stream storage, 100 km pipeline and 7 pump stations to supply 20 000 ML high surety summer irrigation water for dairy production. Early scoping stage with preliminary information being sought on demand for water. A preferred option was submitted to Tasmanian Irrigation Board in June 2014. Investigations into engineering design, environmental and economic assessments underway. Construction time estimated June 2015 and December 2017. Estimated total capital cost is $60.7 million. Estimated Commonwealth requested contribution is $41.8 million. 9 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Swan Valley TAS Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) Dam and 38 km pipeline to deliver 2000 ML from Swan River to high value irrigated agriculture, including viticulture, grazing, irrigated cropping and walnut production. Business case expected to be completed in 2014. Estimated total capital cost of $12 million. Estimated Commonwealth requested contribution is $7.7 million. 18 2. Likely to be sufficiently developed to allow consideration of possible capital investment within the next 12 months # Project Name State Description of Project 10 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: North Esk TAS Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) 3150 ML dam and pipelines. To provide water security for existing and expanded high value irrigated agriculture. Pre-feasibility studies underway with analysis of preferred option expected to be completed in September 2014. Construction expected from December 2014 to December 2016. Estimated total capital cost is $13 million. Estimated Commonwealth requested contribution is $8.8 million. 19 3. Could warrant future consideration of possible capital investment, but less advanced in stage of development # Project Name State Description of Project 11 Gippsland: Lindenow Valley Water Security Project (Mitchell River) VIC Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Construction of a 17 GL dam and mitigation works. To enable winter flows for use during the summer irrigation months and expand area. Mitigation works to offset dam in Nicholas River. Business case to be developed. Could commence in 2014/15. Estimated cost $50-100 million. Including capital $40-87 million, $2.5 million for development of business case and completion of necessary approvals, and $9 million for mitigation works. Cost of entitlements would depend on funding arrangements and level of government support. 12 Emu Swamp Dam – Severn River, Stanthorpe (MDB) QLD Stage of development: Decision to Proceed (Stage 3) Two options: 1. A 10 500 ML urban and irrigation supply dam, with the potential to support growing demand for horticultural water in the Stanthorpe Shire. Associated inundation area of 196 ha. 2. A 5000 ML urban water supply dam with pipelines linking the dam to the Mt Marlay Water Treatment Plant. Environmental Impact Assessment is being completed. Expected to cost $76 million. Construction will take 15-18 months. Proposed dam would be located in the Murray–Darling Basin. Any water use associated with the new infrastructure would need to comply with long term sustainable diversion limits (SDL) described in Schedule 2 of the Basin Plan. If the dam were to create new entitlements in a catchment that already uses its full SDL these would need to be offset elsewhere in the catchment. Dam design would need to meet environmental objectives and impacts on downstream flows would need to be considered by the state. 13 Nathan Dam, Dawson River QLD Further information is required on the current demands by water users to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth. Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) and Decision to Proceed (Stage 3) Dam 888 312 ML and 149 km pipeline. To deliver water to Dalby and Surat Basin to support industrial and mining development, power and irrigated agriculture. Business case on demands and locations under development and obtaining environmental approvals. Estimated cost $1.4 billion (2012). 14 Wellington Dam Revival Project WA Stage of development: Decision to Proceed (Stage 3) New channels and pipelines to divert hyper-saline flows away from Wellington Dam to secure improve water quality (saline) and increase irrigation. Business case developed 2014. Estimated cost of $110 million. 20 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 15 Apsley Dam Walcha NSW More information is required on initial investigations to determine feasibility. Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Originally proposed in 1970s to supply water for hydro electrical generation and would have included provisions to pump water over the Great Dividing Range to the McDonald River (which flows into the Namoi River), in the Murray Darling Basin. New South Wales Government abandoned the project in 1986 when the area was designated part of the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park, due to the significant natural and cultural values of the area. Elements of the national park including Apsley Gorge were inscribed on the Register of World Heritage Sites in 1994. Estimated cost in 1984 was $1063 million. In 2014 terms this translates to approximately $3267 million. 16 Lostock Dam enlargement – Hunter Valley NSW Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) Enlargement of the Lostock Dam to increase capacity to secure Lower Hunter’s water needs. Capacity could be increased by adding spillway gates, or augmented further by enlarging the embankment. Project would deliver increased water security for Hunter region including urban users and power and mining sectors. Options to couple the dam augmentation with a water transfer schemes downstream have also been raised. Estimated cost of $130 million (NSW State Water). Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 21 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 17 Mole River Dam (MDB) NSW Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) A dam on Mole River 300 GL near the confluence of the Dumaresq/Severn and Mole Rivers, approximately 50km west of Tenterfield. To restore environmental flows into the Murray Darling Basin System and improve regional water security to the community and primary industries. Early scoping stage with potential recognised and limited investigations. 10 years to operation. The estimated cost is $500 million. Proposed dam would be located in the Murray–Darling Basin. Any water use associated with the new infrastructure would need to comply with long term sustainable diversion limits (SDL) described in Schedule 2 of the Basin Plan. If the dam were to create new entitlements in a catchment that already uses its full SDL these would need to be offset elsewhere in the catchment. Dam design would need to consistent with meeting environmental objectives and impacts on downstream flows would need to be considered by the basin state. 18 Needles Gap (MDB) NSW Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) A dam 600GL storage on Belubula River (Needles Gap).To enhance water security in the Lachlan and throughout the Central West of NSW. Under the Murray Darling Basin Plan a new dam in the Lachlan can only be built for water security and not increased water extractions. Cost estimates from State Water are $700 million for large dam (660-700GL). Proposed dam would be located in the Murray–Darling Basin. Any water use associated with the new infrastructure would need to comply with long term sustainable diversion limits (SDL) described in Schedule 2 of the Basin Plan. If the dam were to create new entitlements in a catchment that already uses its full SDL these would need to be offset elsewhere in the catchment. Dam design would need to meet environmental objectives and impacts on downstream flows would need to be considered by the basin state. On 13 June 2014, Deputy Premier the Hon. Andrew Stoner made an announcement at the NSW Nationals Annual General Conference committing the NSW Government to delivering the Needles Gap Dam, including committing $1 million for a feasibility study, with more than $100 million expected to be spent on building the dam. 22 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 19 Burdekin Falls Dam (including Water for Bowen) QLD Further information on demand for water is required to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth. Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) 2 m raising of the dam to increase capacity by 590 000 ML to a total capacity of 2 445 000 ML. Would provide additional water supply security for the Burdekin region. SunWater has delayed further work until economically viable demand for more water in the region is demonstrated. Existing entitlements are currently not fully utilised. 20 Connors River Dam Sarina QLD Further information on demand for water is required to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth. Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) A 373 662 ML dam and a 133 km pipeline (1.5 m diameter) to transport water to Moranbah. Expected to yield 49 500 high priority supply of which 46 500 would be available for commercial users and rest for town water, stock and domestic uses. Federal Government EIS approval was granted in 2012. Recommendations (including obtaining additional permits) are yet to be implemented. Estimated cost is $1.17 billion. 21 Fitzroy Agricultural Corridor – construction Rookwood weir and raising Eden Bann Weir QLD Further information is required on this project to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth. Stage of development: Decision to Proceed (Stage 3) Potential construction of a new weir (Rockwood) and/or raising of existing weir (Eden Bann) to capture and store unallocated water resources available in the system. This water would meet identified short-tomedium term urban and industrial water resource needs of the Lower Mackenzie-Fitzroy sub-region that cannot be met by water trading and/or efficiency measures alone. Total cost is estimated at $434 million. 23 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 22 Mitchell River System QLD Stage of development: Unknown Located in far North Queensland. The Department of Natural Resources and Water (now DERM) investigated the potential of installing a dam at the Pinnacles on the Mitchell River which could store up to 158 000 ML. Following a rigorous assessment the proposed dam site was deemed unsuitable due to “potential cultural and environmental issues, remoteness of the site” (Northern Australia Land and Water Taskforce, 2010). The current Water Resource Plan does not make allowances for future agricultural expansion and there is little development in the river system. A CSIRO investigation could be undertaken, similar to that undertaken for the Flinders and Gilbert Rivers. A general lack of scientific information exists for many of these remoter regions and any decisions on major developments would require significant investment in a broad range of studies including environmental flows, overland flows and flood patterns, impacts on biodiversity, strategies to reduce land use degradation, soils surveys and Indigenous protected areas (Northern Australia Land and Water Taskforce, 2010). The most intense development in the upper Mitchell River includes the relatively large water storage, Southedge Dam, also known as Lake Mitchell. This can hold up to 129 000 ML of water, and has remained unused since its construction (Northern Australia Land and Water Taskforce, 2010). 23 24 North Queensland Irrigated Agriculture Strategy: FlindersGilbert, large scale infrastructure proposals (e.g. IFED) and on-farm development QLD Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Potential projects include: The Etheridge Integrated Agricultural Project involving off-river water storage in constructed lakes (combined capacity of 2 million megalitres) in the Gilbert River valley. Overland gravity channels supplying water to pumping stations for trickle-tape irrigation. Or Instream dams on the Gilbert River – two potential in-stream dams (Dagworth and Green Hills) to support a potential irrigation development of 20 000 to 30 000 ha supporting year round mixed irrigation and dryland cropping (CSIRO report) Off-stream storage in the Flinders River catchment – off stream storages such as farm dams to potentially deliver an irrigation development totalling 10 000 to 20 000 ha supporting year round mixed irrigation and dryland cropping (CSIRO report) The Flinders River Agricultural Precinct – A pathway for expansion and diversification in the development of new and existing agricultural industries using available water allocations in the Flinders River. This proposal is seeking investment to integrate intensive irrigation farming into existing grazing systems. 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 24 Nullinga Dam Cairns QLD Further information is required on best option to supply future water demands to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth. Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) A 364 000 ML dam. To provide water for urban growth around Cairns, expansion of agriculture and power generation. It is estimated the dam is unlikely to be required before 2020. The economic viability of the dam against other options for water supply is being investigated by a water advisory committee (established May 2014). SunWater commenced a feasibility study in 2009 to be completed in 2012. Cost estimates range from $274.5 million to $442.7 million depending on the size of the dam. 25 Urannah Dam – Collinsville QLD Further information is required on the feasibility of the project to determine if warrants further consideration by the Commonwealth as undertaken more than 10 years ago. Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) New Dam in two stages – 863 000 ML and 1,500,000 ML Large scale irrigated agriculture (30 000 ha), coal mining in the Bowen and Galilee Basins and future power generation at Collinsville. Desk top study completed more than 10 years ago. Estimated cost $215 million (2014 dollars). 26 Ord Irrigation Stage III (water infrastructure components) WA, NT Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Raise the Lake Argyle spillway and upgrade and extend the existing irrigation channels to deliver water to the Northern Territory (M2 channel). To expand the Ord River Irrigation Scheme north east of Kununurra into the Northern Territory, potentially increasing irrigable land in the region by around 14,500 ha. Estimated cost of $80 million to raise the spillway and $50 million for M2 channel. Thorough land-use suitability of analysis of the proposed development area is required to clarify the scope and coverage of suitable soils and the nature and extent of key production risks. If the stage III is fully realised, significant infrastructure and public works will be required, at an estimated cost of over $425 million (not including a new sugar mill), much of which is likely to involve Commonwealth funding (partially or fully). 25 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design # Project Name State Description of Project 27 Pilbara and/or Kimberley irrigated water pipeline system WA Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) The Western Australian Government is investigating the potential for irrigated water pipelines systems in the Pilbara and Kimberley to underpin large-scale irrigated agriculture in these regions. The project will investigate the potential to pipe an estimated 200 GL/yr of surplus fresh water from mines in the Pilbara. The Western Australian Government’s follow up letter of 9 July 2014 (Maree De Lacy, Director General, Department of Water) outlines a Pilbara Mine Dewatering – water for agriculture project. The project would develop new agriculture nodes to optimise over 160 GL/yr of water available for mine dewatering. An investment of $100 million would support land development and piping to agricultural precincts, enhancing diversification and exports. 28 29 30 31 Expanded Horticulture Production on the Northern Adelaide Plains - Waste Water Re-use Intensive Livestock and Horticulture Expansion – Northern Dams Upgrade – Clare Valley Exploring off-stream storage opportunities to increase water availability for agricultural development SA Upper Adelaide River Dam / off stream storage NT Stage of development: Assessing Feasibility (Stage 2) Expansion of horticulture production through an upgrade of the Bolivar treatment plant to provide an additional 20 GL of reclaimed water. Estimated capital cost $170 million. SA Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Upgrading Bundaleer, Baroota and Beetaloo dams to Australian National Committee of Large Dams (ANCOLD) Standards. To support 1200 ha of new horticulture, dairy and broiler chicken activities. Estimated capital cost $75 million. NT Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Significant post peak flood flows to be harvested and stored off-stream to facilitate agricultural and regional development. The drainage basins with the most potential (in order of decreasing order of potential) are in the Top End and include Daly, McArthur, Roper, Victoria, Moyle, Adelaide, Mary, Baines and Blythe (Arnhem Land). A surface water assessment is required to define the quantity of water flowing from river basins that is divertible at strategically located sites close to soils of agricultural potential and other strategic uses. Assessing land suitability for irrigated agriculture is also required. The cost of the project is unknown. Stage of development: Early Scoping (Stage 1) Two options: Upper Adelaide River Dam or Upper Adelaide River offstream storage Very early scoping of physical and economic feasibility. Estimated cost of $500-1000 million for the dam or $200 million for the off-stream storage. 26 Appendix C: Potential projects identified by state and territory governments and others for consideration In total, 63 projects have been identified through consultation with the state and territory governments and others. 1. Project already funded with existing Commonwealth assistance 1 Chaffey Dam (MDB) NSW 2 Menindee Lakes NSW 3 Nimmitabel Lake Wallace NSW 4 Great Artesian Basin Sustainability Initiative NSW, QLD, SA 2. Likely to be sufficiently developed to allow consideration of possible capital investment within the next 12 months 5 Gippsland: Macalister Irrigation District / Southern Pipeline – Sale - Maffra VIC 6 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Southern Highlands TAS 7 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Scottsdale TAS 8 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Circular Head TAS 9 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: Swan Valley TAS 10 Tasmanian Irrigation Tranche II: North Esk TAS 3. Could warrant future consideration of possible capital investment, but less advanced in stage of development 11 Gippsland: Lindenow Valley Water Security Project (Mitchell River) VIC 12 Emu Swamp Dam – Severn River, Stanthorpe (MDB) QLD 13 Nathan Dam, Dawson River QLD 14 Wellington Dam Revival Project WA 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design 15 Apsley Dam – Walcha* NSW 16 Lostock Dam enlargement – Hunter Valley NSW 17 Mole River Dam (MDB) NSW 18 Needles Gap (MDB) NSW 19 Burdekin Falls Dam (including Water for Bowen) QLD 20 Connors River Dam – Sarina QLD 21 Fitzroy Agricultural Corridor – construction of Rookwood Weir and raising Eden Bann Weir QLD 22 Mitchell River System, Far North Queensland QLD Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 27 4. Likely to be suitable for further consideration for possible assistance to accelerate feasibility studies, cost benefit analysis or design 23 North Queensland Irrigated Agriculture Strategy: Flinders-Gilbert, large scale infrastructure proposals (e.g. IFED) and on-farm developments QLD 24 Nullinga Dam – Cairns QLD 25 Urannah Dam – Collinsville QLD 26 Ord Irrigation Stage III (water infrastructure components) WA, NT 27 Pilbara and/or Kimberley irrigated water pipeline system WA 28 Expanded Horticulture Production on the Northern Adelaide Plains - Waste Water Re-use SA 29 Intensive Livestock and Horticulture Expansion – Northern Dams Upgrade – Clare Valley Exploring off-stream storage opportunities to increase water availability for agricultural development Upper Adelaide River Dam / off stream storage SA 30 31 NT NT 5. Likely to occur without direct Commonwealth involvement 32 Cobar water supply (MDB) NSW 33 Forbes water supply (MDB) NSW 34 Menindee Road Bore (MDB) NSW 35 Walken Bore $2.5M (MDB) NSW 36 Bendigo Northern Growth Area Flood Protection Scheme VIC Expansion Of Intensive Horticulture And Livestock – Murray Bridge to Onkaparinga Pipeline Off-Take and Storage Upgrading under-capacity drain system to avoid flood damage - Port Road Stormwater Management (Water Proofing the West Stage 2) SA 37 38 SA 6. More information is required from state and territory government to inform categorisation 39 Gwydir River including Horton River storage (MDB) NSW 40 Macquarie River (MDB) NSW 41 Pindari Dam NSW 42 Refurbishment of monitoring assets including for groundwater and surface water gauges NSW 43 Works and measures of weirs and locks in NSW, with a particular focus on the Murray NSW 44 Bunyip Irrigated Agriculture Project – SE Melbourne VIC 45 Northern Program VIC 46 Werribee Irrigation District VIC 47 Borumba Dam raising QLD 48 East Normanby River Dam QLD 49 QLD 52 Hells Gate Dam and Mount Foxton, Burdekin River Integrated Food and Energy Developments (IFED)/ Etheridge Integrated Agricultural Project Georgetown Other dams (Battle Creek Dam, Blackfort Dam, Cameron Creek Dam, Cave Hill Dam, Chinaman Creek Dam, Corella Dam (raising), Corella River Dam, Gunpowder Creek Dam, Leichardt River Dam) Raising the Fairbairn Dam wall – Emerald 53 South East Queensland flood mitigation infrastructure investigation QLD 54 Tully Millstream Dam QLD 55 Gascoyne Food Bowl Initiative (Carnarvon Trunk main irrigation water delivery) WA 56 Investigatory work in the Manjimup area (capture and store run-off/potential dam sites) WA 57 Reviving Rural Dams WA 50 51 28 QLD QLD QLD 6. More information is required from state and territory government to inform categorisation 58 WA Underground dams – climate resilience through small scale aquifer recharge WA 59 Fitzroy Dam (Northern Australia Integrated Irrigation Industry Development) 60 Brown Hill and Keswick Creeks flood mitigation scheme - Adelaide SA 61 Sustaining Irrigated Agriculture in the Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges - Bypassing Low Flows SA 62 Exploring potential dam opportunities in Victoria, Baines River and Katherine/Daly region NT 63 Managed aquifer recharge - various locations NT Project identified by the Water Infrastructure Ministerial Working Group 29 Appendix D: Indicative water infrastructure project development phases used by the Ministerial Working Group (provided by the Department of Agriculture) 30 31 Appendix E: Consideration of funding and financing models for water infrastructure Alternative financing mechanisms can increase private sector participation in water infrastructure development by removing impediments. This can provide governments with greater flexibility to reduce budget outlays and improve opportunities to share risk with private sector investors. Effective infrastructure planning, prioritisation and selection processes are critical, not only in considering these mechanisms, but to attract private sector investment in the first instance. Implementing an effective financing model cannot overcome the costs of delivering a poorly planned or selected project. Funding and financing requirements (and whose responsibility they should be) should be considered across the full lifecycle costs of infrastructure, including operational and ongoing costs for maintenance. The preferred funding and financing model is likely to vary depending on the specific characteristics of each water infrastructure project. A range of potential options to leverage private investment is canvassed below. Further work is likely to be required for specific projects of merit to identify the most appropriate model that balances private sector involvement against risks to the Commonwealth. Public Private Partnerships A public private partnership (PPP) is an arrangement between a government and the private sector to design, build, finance, and, in some cases, operate and/or maintain an infrastructure project such as a road, school or hospital. These arrangements leverage private investment and potentially capture efficiencies resulting from private sector involvement. Under PPP arrangements, new infrastructure is typically partially or wholly financed by the private sector. This finance is repaid either through user charges, such as water entitlements, or availability payments from the Government. In an availability payment arrangement, the private partner in the PPP finances all or part of the project’s construction costs, assuming the risk involved, and recoups these costs over time through availability payments made by the Government, that may be partly sourced from the project’s revenues. Generally the private partner will also be responsible for operations and maintenance of the infrastructure and receive their payments only on the condition the asset is available for use to a set of required standards. Tasmanian Irrigation’s schemes are an example of a water infrastructure public private partnership and a potential model for future water projects. Concessional Loans A concessional loan is an arrangement where a project proponent receives a loan with a reduced interest or ‘concessional’ rate for an agreed period. Concessional loans offer a lower cost of capital to project proponents compared to the market rate. Concessional loans effectively leverage the Commonwealth Government’s lower cost of debt to reduce overall financing costs for the private sector and the project as a whole. A concessional loan places a considerable level of risk on the Commonwealth, with a great deal of legal and financial due diligence required, as well as a high level of comfort in the ability of the ongoing revenue streams of the project to be able to meet debt obligations. The Commonwealth has recently announced it will provide a concessional loan to accelerate the delivery of the WestConnex road project in Sydney. The revenue stream for the WestConnex project will build on the strong, established patronage on the existing M4 and M5 corridors, minimising the repayment risk to the Commonwealth. The application of this mechanism to finance water infrastructure would require investigation of whether or not the revenue stream generated by the project is capable of repaying the 32 principle and interest of a Commonwealth concessional loan, without impeding the project’s financial viability. Debt guarantees A Commonwealth debt guarantee ensures repayment of debt, should the project not be able to service its debt obligations. The guarantee enhances a project’s credit worthiness and reduces the project’s borrowing costs, as the guaranteed debt will be priced close to the rate of Commonwealth Government debt and not as debt exposed to project risks. This means credit becomes more easily available, increasing the number of entities eligible to compete for tender. Debt guarantees effectively transfer project risk onto the Commonwealth, meaning a high level of detailed due diligence needs to be undertaken. Given this considerable exposure to project risk, the Commonwealth is yet to provide a debt guarantee to a road project despite many having established brown field revenue streams. Water revenues would appear significantly more risky. Demand guarantees Guarantees can also be structured to reduce demand risk for the private sector, facilitating greater potential for investment and competition for tender. Guarantees may be offered over aspects such as minimum take out of water for a water infrastructure project. Should a project’s demand fall below the guaranteed benchmark, the Commonwealth would step in to make up the difference in revenues to that minimum benchmark. A variation on this guarantee floor is a cap and collar approach, where the Commonwealth tops up revenues when demand falls below the guaranteed floor, but also conversely steps in and collects project revenues above a designated threshold. In order to offer a guarantee, the Commonwealth must have a robust understanding of expected project demand and revenue, more so than when demand risk lies solely with the private sector. Contingent loans (income or other measure) Income contingent loans are loans where repayment is dependent on future income or revenue streams (such as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme)*. The feasibility of applying this to water users, rather than developers, may be questionable given the significant variability in climate and associated farm income. To date, this mechanism has not been used in the agricultural sector (for example, as an alternative to grants-based drought policy). Further work would be required to understand how such an initiative would interact with other policies and taxation arrangement currently available to farmers to manage variability in farm income. Betterment levies Betterment levies (or taxes) attempt to capture the increased value of private land arising from new public infrastructure or re-zoning and are used to reduce the required capital contributions of governments. The levy is designed to capture part of the increase in value relating to the zoning or new infrastructure, rather * Chapman, B 2006, Income contingent loans as public policy, Occasional paper 2/2006, Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, Canberra. 33 than the general land price increases which would have occurred regardless†. These levies have been criticised overseas as a form of infrastructure finance because of the high rates imposed, combined with the uncertainty in accurately pricing the land-value gain associated with the public infrastructure.‡ Betterment levies can be used when conditions for landowners have been improved as a result of infrastructure being built. A transport example may be if land in commercial precincts becomes more accessible, say through a light rail line being built nearby, thus increasing the overall value of the land. In the case of water infrastructure it is not clear that there would be these “secondary benefits”. It may be beneficial for a farmer requiring irrigation to have water infrastructure built nearby, thus increasing the overall value. However, in paying for the water they use, the value they receive is being captured. A betterment levy could be viewed as double charging in this instance. Alternatively, a betterment levy could be applied to residents of a region should the value of their property increase from the development of water infrastructure. Debt financing A government can issue bonds/debt securities through its central borrowing agencies to raise general funds. The central borrowing agencies do not undertake purpose-specific borrowing: while project-specific infrastructure bonds were once used in Australia, this practice ended with the financial reforms in the 1980s and 1990s.§ Debt financing is the method the Commonwealth currently uses to raise grant funding. It isn’t considered practical to develop new instruments, such as water bonds specifically for water infrastructure as they would attract an extra element of risk when viewed by the market. It would essentially lower the effectiveness of debt financing by renaming a Commonwealth Government security. † Commonwealth of Australia 2010, Australia's future tax system, report to the Treasurer, www.taxreview.treasury.govl.au/ ‡ Peterson, G E 2009, Unlocking land values to finance urban infrastructure, The World Bank, Washington, DC. § Productivity Commission 2014, Public infrastructure, Draft Inquiry Report, Canberra. 34