L563F10

L563F10.A05 Meredith Tamminga

Application of Transmission and Diffusion to Loanwords

The lexicon is the linguistic module most amenable to borrowing; it represents one pole of the “cline of borrowability” described by Sankoff (2002). People’s vocabularies continue to grow throughout their lifespans, indicating that the closing of the critical period does not put an end to a speaker’s ability to learn new lexical items. It is thus unsurprising that loanwords are common across the world’s languages. In the most obvious case, that of contact between adult speakers of different languages, loanword development should show the patterns characteristic of diffusion, rather than transmission. Another possible scenario, though, is that loanwords could enter a language during an extended period of bilingualism within the speech community. In this case, loanwords might cross the boundaries across the languages in the process of natural language acquisition and show more characteristics of transmission. I will explore the case of loanwords in Turkish and relate them to the transmission-diffusion distinction.

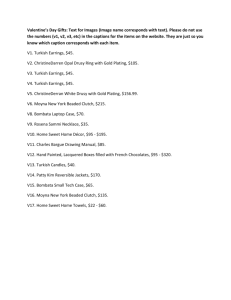

The most common origins of loanwords in Turkish, according to the 2005 edition of the

Turkish Language Association’s Güncel Türkçe Sözlük

(as reported in Wikipedia), are:

Language of origin

Arabic

French

Persian

Number of loanwords

6463

4974

1374

Percent of vocabulary

6.2

4.8

1.3

Italian

English

Greek

Latin

German

632

538

413

147

85

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.1

0.1

The history of the bulk of the loanwords from Arabic and Persian certainly weighs in favor of diffusion as the mechanism for their adoption. They came into the language not through the vernacular kaba Türkçe

(‘rough Turkish’) but through fasih Türkçe

(‘eloquent Turkish’), the high register used for administrative and literary functions. The use of Persian loanwords is said to convey romanticism while the use of Arabic loanwords often has a religious connotation. The high-prestige, learned nature of these contexts strongly indicates that these loanwords diffused across the upper echelons of society and were learned by adults well past the critical period.

In many cases, loanwords in Turkish were supposed to be replaced by words of “pure”

Turkic origin during the Turkish Language Reform in the 1930s. The outcome of this purification attempt was mixed; Wikipedia gives a list of 460 Ottoman Turkish words of

Arabic origin that were supposed to be replaced, and notes for 264 of these cases (57%) that the older words are still in common use alongside their intended replacements. Often the new and old words developed different meanings or connotations. For example, the

Persian loan taze is used to mean ‘fresh’ while its Turkish replacement, yeni , is used to

1

mean ‘new’. This wholesale replacement of lexical items might be considered an example of diffusion itself, albeit a somewhat unnatural one, as the new words would have had to be learned by adults before they could be passed on to new generations of learners.

Structurally, an interesting characteristic of loanwords in Turkish is that while the phonemes are nativized to the Turkish phoneme inventory (for example, French nasalized vowels are nativized to vowel + nasal sequences), they do not have to obey the rule of vowel harmony. Although often vowel harmony is described as an assimilatory phonological process, in Turkish it constrains the underlying phonological forms of native lexical items as well. Words are only allowed to contain either all front vowels (<i e ü ö>) or all back vowels (<ı a u o>). French-origin loanwords like simülasyon

‘simulation’ or favori ‘favorite’ do not conform to vowel harmony, while their Turkish counterparts

ö grence or gözde

of course do. The significance of this divergence from native language structure for the distinction between diffusion and transmission is not entirely clear to me, but it seems like it might be relevant. Does the transmission of forms that don’t obey vowel harmony after diffusion from other languages suggest that

This is a longstanding problem; do the structural constraints on Turkish lexical items is no longer in effect?

Finally, an interesting issue which is raised in the exploration of loanwords in Turkish relates to compound words. Apparently pre-war Ottoman Turkish used Persian rules such as the genitive construction to form compound words, although it is not entirely clear how productive these rules were or whether they even applied to non-Persian-origin words. In modern Turkish this practice has been abandoned except in specialized domains, but it would be interesting to know if the diffusion of compound words introduced a productive but non-native word-formation rule into earlier stages of the language. childen learn loan words early enough to modify vowel harmony?

2