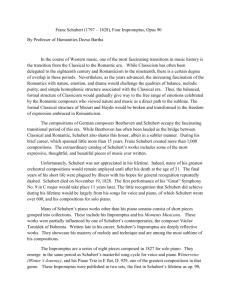

Concerning the grundgestalt, consider the first phrase

advertisement