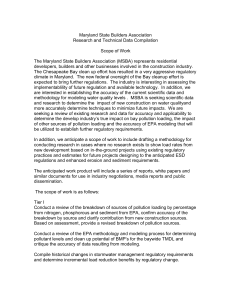

chapter 2. overview of the contamination problem

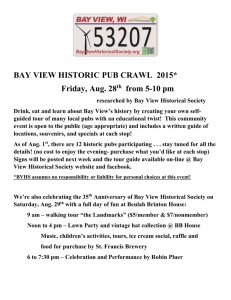

advertisement