Notes -Sept 11 - Ocean Circulation

advertisement

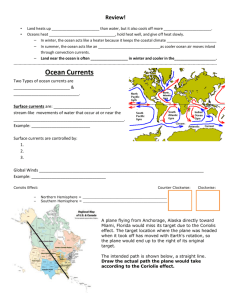

Oceans 11 – Dalesandro Notes – Ocean Circulation -Ocean circulation refers to the movement of water around the Earth’s oceans. -There are two main categories of ocean circulation: Surface Currents – Involve the uppermost 10% of the world ocean (they are mostly wind driven). Deep Ocean Circulation – Also called thermohaline circulation (this is mostly density driven). 90% of the Earth’s ocean water moves this way. Surface Currents: Powered by winds. Transfer heat to polar regions (warm water currents) or cool down tropical regions (cold water currents). Distribute nutrients around the globe. Scatter and spread organisms, especially plankton (microscopic animals and plants living in seawater). -Due to the Coriolis effect, surface currents in northern hemisphere bend to the right and surface currents in the southern hemisphere bend to the left. -Continents, basin geography, and the Coriolis effect combine to guide currents into a circular pattern called a gyre. Example: The North Atlantic Gyre moves water from the Gulf of Mexico, along the eastern seaboard of the United States, across the north Atlantic toward the United Kingdom, down past Spain to north Africa, and finally across the Atlantic again to the Gulf. -Gyres are important because: They help to spread nutrients around the world’s oceans. They aid in migration and movement of many sea creatures. They may help to regulate Earth’s climate by moving warm and cold water to various areas. They can help keep the ocean clean by removing pollutants and garbage. Deep Ocean Currents (Thermohaline Currents) -Thermohaline currents are driven by density differences in the water. Water density depends on its temperature and salinity. At the earth's poles, when water freezes, the salt is excluded, so a large volume of dense, cold, salty water is left behind. When this dense water sinks to the ocean floor, more water moves in to replace it, creating a current. This current begins with the cold water near the North Pole and heads south between South America and Africa toward Antarctica, partly directed by the landmasses it encounters. In Antarctica, it gets recharged with more cold water and then splits in two - one part heads into the Indian Ocean and the other into the Pacific Ocean. As the two sections near the equator, they warm up and rise to the surface. When they can't go any farther, the two sections loop back to the South Atlantic Ocean and finally back to the North Atlantic Ocean, where the cycle starts again. This creates the global conveyor belt.