CompTech4Postsecondary students w disabilities-I

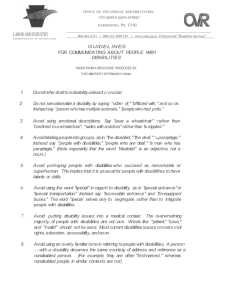

advertisement