Human rights and transnational corporations: the

advertisement

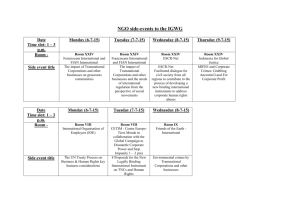

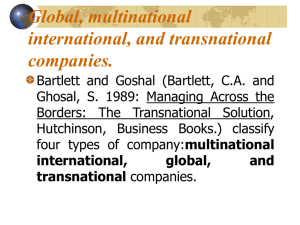

Human rights and transnational corporations: the way forward A summary of discussion at the International Law Programme Discussion Group at Chatham House on 7 June 2005; participants included representatives from business, law firms, academics, and representatives from government departments. This summary is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the meeting. High Commissioner’s Report A speaker summarised the report of the Commissioner of Human Rights on the responsibilities of transnational corporations and related business enterprises with regard to human rights of 15 February 2005 (E/CN.4/2005/91). The report reviewed existing initiatives and standards and compared their scope and legal status, in particular the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the United Nations Global Compact, and the draft Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with regard to Human Rights (draft Norms). The report makes three general assumptions. The first is that business has to operate in a responsible manner, including through respecting human rights. Many businesses have already adopted voluntary guidelines and codes of conduct. Secondly, business can provide an enabling environment for the enjoyment of human rights through investment, employment creation and the stimulation of economic growth. But the activities of business have threatened human rights in some situations and individual companies have been complicit in human rights violations.. Thirdly, the review of existing initiatives and standards on business and human rights indicates that there remains a gap in understanding the nature and scope of responsibilities of business with regard to human rights. The report mentioned difficulties in identifying what the responsiblities of business are (that is, their responsibility to respect and to support human rights, and not to be complicit in human rights abuses), in identifying what are the boundaries of those responsibilities (the question of “sphere of influence”), in identifying which human rights business is responsible for, and in determining how the responsibilities of business could be guaranteed. Further questions were whether there should be a United Nations statement of universal standards setting out the responsibilities of business entities with regard to human rights, what would the legal nature of those responsibitlies be and what tools were needed to promote respect for human rights within the activities of business. The report had identified two concepts for further analysis: the concepts of complicity and sphere of influence. There was a need for continued dialogue and consultation among all stakeholders. The report also identified a wish to discuss further the possibility of establishing a United Nations statement of universal human rights standards applicable to business. But what legal force would such a statement have? The speaker emphasised that the report had reiterated that states bore the primary responsibility for human rights. The report had suggested that assistance should be given to states in the area of business and human rights and a compilation of best state practice was needed. But this aspect was not included in the final recommendations. Resolution The speaker explained that there had been a great deal of debate at the Commission in Geneva, but a resolution had finally been adopted (E/CN.4/2005/L.87). The resolution had recognised that transnational corporations and other business enterprises can contribute to the enjoyment of human rights. The resolution had requested the UN Secretary-General to appoint a Special Representative on the issue of human rights and business with the following mandate (to which the speaker added comments - in square brackets below): (i) to identify and clarify standards of corporate responsibility and accountability for transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights; [it was intentionally left ambiguous as to whether this covered existing or new standards] (ii) to elaborate on the role of states in effectively regulating and adjudicating the role of transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights, including through international cooperation;[no distinction is made here between host state and home state of the business concerned] (iii) to research and clarify the implications for transnational corporations and other business enterprises of concepts such as ‘complicity’ and ‘sphere of influence’; (iv) to develop materials and methodologies for undertaking human rights impact assessments of the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises; (v) to compile a compendium of best practices of states andtransnational corporations and other business enterprises. Other aspects of the resolution to which the speaker drew attention included the recognition that many submissions had been made to the High Commissioner which had not been specifically reflected in the report, and the Special Representative was asked to take these into account. The Special Representative was asked to consult with all stakeholders. And s/he was also asked to convene sector-specific meetings with industries. The speaker considered that there were now three principal questions: to what extent are the existing standards adequate; if they are, should there be better presentation of them; if not, what should be the next steps? What are the roles of the host and home states for ensuring responsible behaviour by companies? What scope is there for research on complicity and sphere of influence? Business Another speaker stresssed that states are the principal duty-bearers of human rights; there was a risk of letting states off the hook; business should not be made to be surrogate governments. There was a slight disconnect between the report and the resolution, but from the point of view of business, the resolution was good, and avoided the polarisation that occurred after the draft UN Norms had been presented. There was no reference to a non-international framework in the resolution. There were now many initiativesin the area. It was important that the Special Representative to be chosen should be one who could command support from all the stakeholders. The US business community probably had a similar attitude to that of the UK: the process deserves support, there is no support for the UN draft norms; there should be no monitoring by reference to those norms; they have no legal standing. There were many problems with the norms; too much had been claimed for them; the process had been wrong. For the future things should be done in an open and inclusive manner. It was noted that the debate had largely taken place between stakeholders from the developed world. It had been found difficult to engage the developing world; it was necessary to ensure that local businesses in the developing world had their full say. The report had concluded that there was a need to consider ways to include more effectively the views and opinions of States and stakeholders from developing countries. The use of civil litigation A speaker introduced a project being carried out at Chatham House; a number of the issues being addressed were identified for further investigation in the report of the High Commissioner. The project was looking at how the existing private civil claims structure works internationally with reference to harm which might be caused by a transnational corporation in a developing country. There was no question of the project encouraging the irresponsible pursuit of speculative claims. The project focused on private civil compensation claims, which are enforceable by individuals, not state agencies, and it concerned the existing system for enforcing private rights transnationally, not an entirely new system. While the language of human rights was not used, the project covered much of the same ground. It looked at tort– type claims of harm to the person, and to their property from industrial processes, products, and working conditions, trespass to the person (these more in the context of the extent to which a company can be liable for the conduct of its associates), economic torts and abuse of dominant position in competition law in the trading context. It examined how the management structure of a TNC might affect the claims against it, in particular management lines running across a group, and the problem when it is associates which are the cause of harm, such as suppliers, contractors and joint venture/consortium partners and the circumstances in which a TNC might be held liable for the harm caused by those associates. This relates to the “sphere of influence” and “complicity” issues. This raises difficult issues under UK law relating to the circumstances in which a person, including a company, owes a duty of care to people who have suffered as a result of action by others,causation, joint liability of one kind or another and attribution of the knowledge, acts or omissions of one individual to different companies within a group. There were consultations ongoing as to the legal and de facto relationships which might be typical of the sort of organisation which causes harm in this respect, and what considerations might be relevant to the fairness and equity part of the duty of care debate. There was a separate set of problems relating to damage to the environment as ecosystem where there is no human victim to claim recompense and another relating to damage to people’s livelihoods, where there is the problem of the difficulty of recovering for economic loss in negligence. The methodology being used to map, or illustrate, the existing system is to use fictitious case studies taking different types of harm, group management structures and relationships with associates, and jurisdictions. Although the issues of jurisdiction, governing law and cause of action can be considered in the abstract, in practice they do not operate separately, and the case studies will illustrate what the result is in practice. The governing law for the cause of action under UK law (Private International Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1995) will prima facie be the law of the developing host country, although there is a possibility of applying UK law to the matter, or to some issues, where it is “substantially more appropriate” or where the application of overseas law conflicts with principles of public policy, so the project is seeking advice on the law of selected developing countries. There will be similarities between causes of action under common law systems. We also want to look at the position from the perspective of other developed countries, including the US (where, of course, there is the Alien Tort Claims Act, which has caused a great deal of controversy), and European countries such as Germany and France. The project is looking at transnational enforcement– a transnational corporation operating across borders raises the question of where disputes relating to its activities should be heard, and whether it can or should be heard in the courts of its home state. The possibility of having a claim heard in courts other than those of the developing country has particular importance where the developing country has an undeveloped or corrupt legal system. In Europe, the courts of the jurisdiction where a company has its registered office, central administration or principal place of business have jurisdiction over claims against it wherever the activities out of which the claim arises took place. A recent case has confirmed that the Brussels Convention/Regulation means that the defendant may no longer apply to stay proceedings in the UK on the grounds that another forum is more appropriate (the forum non conveniens argument) even where the claimant is not from another EU member state. The only exception to this which is likely to be relevant (and even this is not certain) is where proceedings between the same parties and on the same subject have already been commenced elsewhere. This means that a claim against UK parent company will be heard in the UK. Moreover, if the UK court has jurisdiction over one defendant, it will permit the joinder of other overseas defendants. The requirements are that there is a real issue to be tried between the claimant and the first defendant, that the overseas defendant is a “necessary or proper party” to the claim and that the claims can conveniently be disposed of in the same proceedings. The project will also consider issues of access, or the reality of actually pursuing these claims in home state courts. Funding is likely to be a major issue, as is access to information to get a claim off the ground. The High Commissioner’s report had not discussed the scope for domestic litigation, other than by implication, in assuming that there may not be a possibility for access for justice in developing countries. There was a question as to whether the project was also covering the human rights responsiblities of transnational companies based in countries other that the West, for example, China, India and Brazil. What prospects could there be for civil litigation such as this being carried forward in Chinese courts? There was agreement that any project or process in this subject area should have a properly constituted multi-stakeholder process to allow the issues to be fully addressed.