Dairy Calf Replacements

advertisement

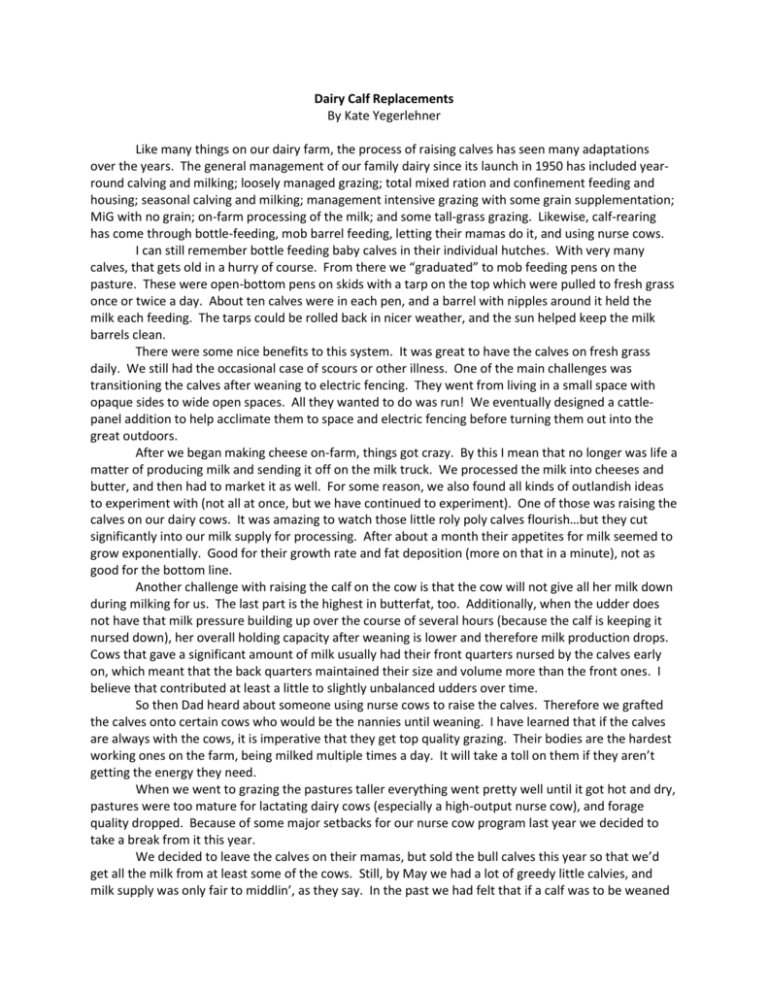

Dairy Calf Replacements By Kate Yegerlehner Like many things on our dairy farm, the process of raising calves has seen many adaptations over the years. The general management of our family dairy since its launch in 1950 has included yearround calving and milking; loosely managed grazing; total mixed ration and confinement feeding and housing; seasonal calving and milking; management intensive grazing with some grain supplementation; MiG with no grain; on-farm processing of the milk; and some tall-grass grazing. Likewise, calf-rearing has come through bottle-feeding, mob barrel feeding, letting their mamas do it, and using nurse cows. I can still remember bottle feeding baby calves in their individual hutches. With very many calves, that gets old in a hurry of course. From there we “graduated” to mob feeding pens on the pasture. These were open-bottom pens on skids with a tarp on the top which were pulled to fresh grass once or twice a day. About ten calves were in each pen, and a barrel with nipples around it held the milk each feeding. The tarps could be rolled back in nicer weather, and the sun helped keep the milk barrels clean. There were some nice benefits to this system. It was great to have the calves on fresh grass daily. We still had the occasional case of scours or other illness. One of the main challenges was transitioning the calves after weaning to electric fencing. They went from living in a small space with opaque sides to wide open spaces. All they wanted to do was run! We eventually designed a cattlepanel addition to help acclimate them to space and electric fencing before turning them out into the great outdoors. After we began making cheese on-farm, things got crazy. By this I mean that no longer was life a matter of producing milk and sending it off on the milk truck. We processed the milk into cheeses and butter, and then had to market it as well. For some reason, we also found all kinds of outlandish ideas to experiment with (not all at once, but we have continued to experiment). One of those was raising the calves on our dairy cows. It was amazing to watch those little roly poly calves flourish…but they cut significantly into our milk supply for processing. After about a month their appetites for milk seemed to grow exponentially. Good for their growth rate and fat deposition (more on that in a minute), not as good for the bottom line. Another challenge with raising the calf on the cow is that the cow will not give all her milk down during milking for us. The last part is the highest in butterfat, too. Additionally, when the udder does not have that milk pressure building up over the course of several hours (because the calf is keeping it nursed down), her overall holding capacity after weaning is lower and therefore milk production drops. Cows that gave a significant amount of milk usually had their front quarters nursed by the calves early on, which meant that the back quarters maintained their size and volume more than the front ones. I believe that contributed at least a little to slightly unbalanced udders over time. So then Dad heard about someone using nurse cows to raise the calves. Therefore we grafted the calves onto certain cows who would be the nannies until weaning. I have learned that if the calves are always with the cows, it is imperative that they get top quality grazing. Their bodies are the hardest working ones on the farm, being milked multiple times a day. It will take a toll on them if they aren’t getting the energy they need. When we went to grazing the pastures taller everything went pretty well until it got hot and dry, pastures were too mature for lactating dairy cows (especially a high-output nurse cow), and forage quality dropped. Because of some major setbacks for our nurse cow program last year we decided to take a break from it this year. We decided to leave the calves on their mamas, but sold the bull calves this year so that we’d get all the milk from at least some of the cows. Still, by May we had a lot of greedy little calvies, and milk supply was only fair to middlin’, as they say. In the past we had felt that if a calf was to be weaned onto pasture alone they really needed a fair amount of fat on their bodies to help them transition through the weaning process. That usually ended up being about 3 months of nursing. Which left a good month and a half of this low-milk business. Not exactly acceptable but we weren’t sure what other options we had at that point. Interestingly, the Lord sent us some new friends (if you’re reading this you’ll know who you are…I’m afraid I can’t remember all your names!) with some pretty cool ideas. They had been at a forage conference in Indiana and arranged to come see our farm while they were here. As we were talking about raising calves, one man mentioned that some had been feeding dairy replacement heifers whey and skim milk. It seemed like such a worthy experiment that we put the weaning nose rings in at the first opportunity. However, the calves would not drink the skim milk we put in tubs for them. We soon came to the conclusion that it was the rings, which made their noses sensitive, that were deterring them from drinking. After removing them, they took to it pretty quickly. We had them on the skim for a few weeks and started out really well but eventually I noticed they seemed to be losing a little of their bloom. Could have been internal parasites starting to work on them. I put some apple cider vinegar in their water daily for a few weeks, which is our usual parasitecontrol method at weaning (that and/or black walnut tincture). It was also really hot, and that may have been affecting their performance too. Around this time, the supply of skim started to not quite meet the demand, so we switched them over to whey. The more we thought about it, the more we realized that maybe the whey would be even better for them anyway. It’s more acidic (like the vinegar), and may also help with parasite protection. Grass-fed whey is touted for many health benefits for people these days, so maybe calves can get some of those same benefits. It also has just a little bit of butterfat left in it, unlike the skim, giving them a little more energy. Protein for growing bodies, too. They really seem to prefer the whey to the skim, and the barrels we feed them in stay cleaner with the whey, too. The young calves certainly need fat in their diet for proper development, so even though the skim and whey have been a great addition, they need a certain period of time on whole milk before switching them over. My youngest calf was a little over a month old when we weaned them off the cows this summer. I sold her shortly thereafter because she looked like she might fall behind the others in growth. The next couple youngest were a little borderline, I think. I’m guessing a couple months on milk might be best, unless you have some very high quality forage to put them on when they stop getting the whole milk. Another concept that was mentioned by the folks who came to our farm that day was something acknowledged in beef cattle that I had never heard of…the grandmother effect. As I understand it, a cow that is a good milker will raise a very fat calf. However, the fatty tissue that builds up in the calf’s udder will result in depressed milk production when she matures. Since her calf will consume less milk, the granddaughter will be more likely to resemble her grandmother in milk production. So perhaps if my calves are getting too fat for too long before weaning they will not be as good of milkers as they could be. Dairying may not be “natural,” but we are trying to find a holistic balance that works for the cows, for the soils, for our customers, and for us. It’s not that we would never go back to raising calves on the barrels, but some of the benefits of letting the cows do it are hard to ignore. For one, it’s simple (the management of grafting onto nurse cows is intense, but once it’s done, it’s pretty simple). No hauling milk daily, no equipment. Also, the calves learn cow behavior quickly from a cow. They learn about electric fencing, about moving from pasture to pasture, about what to eat and what not to eat, about being part of the herd. And there are virtually no health problems (Our most significant health problem in the calves is udder infections…we think it’s transferred by biting flies, and once a quarter is infected it will be blind when she calves. We haven’t figured out how to prevent it yet, but susceptibility to infection seems to be at least somewhat genetic.). So, a final idea from our new friends that I am considering experimenting with next year is maybe using nurse cows again, but only feed the calves twice a day (or once, unless we start out milking twice a day; if once, maybe supplement with whey or skim). The nurse cows will stay with the milk cows, and when they come in they will feed calves instead of going through the parlor. There are a lot of details to figure out. Like adding fencing to keep calves on a pasture rotation, and a place to sort the cows back out of the calf pasture. Maybe we could allow the cows to spend a few days with the calves at first so they will establish a bond to their new mother. Or maybe there is a satisfactory way to do this without even grafting, but instead let each cow take care of her calf once a day. You have to find what works for you and your farm. Every place and everybody is different. We must be so different we haven’t even found what works for us yet! But it is great to network and get new ideas. Be careful not to implement too many new things at once, or it will be harder to know what works and what doesn’t. Life and its circumstances are always changing, and we have to be flexible and willing to make necessary changes. At least if we don’t want to get bowled over. There is a great adventure ahead of us, and it’s only just begun!