A Critique of the Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms

advertisement

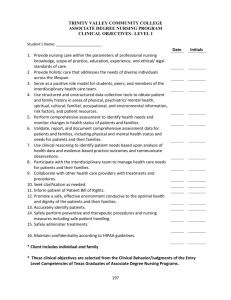

Running head: A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS A Critique of the Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms Bridget Apple, Cathy Bozek, Jessica McClusky, & Christina Suwyn Ferris State University 1 A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine the Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms (TOUS) by Elizabeth Lenz and Linda Pugh. Within the theory’s development, the initial symptoms addressed were dyspnea and fatigue. Representation of single concepts in different clinical populations identified similarities across phases and concepts. The development of TOUS has produced two conceptual levels and incorporated these concepts within a middle range theory plane. At the single concept level, fatigue and dyspnea are seen. The multiple concept level includes the study of fatigue during childbearing and also during dyspnea. At the middle-range theory level, the process of unpleasant symptoms is observed. 2 A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 3 A Critique of the Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms The Theory of Unpleasant Symptoms (TOUS) was introduced in 1995 and has since been used in multiple studies. Its revision in 1997 brought a more general and adaptable theory. The TOUS is a credible middle-range theory that has been used numerous times in nursing research and will continue to be used in the future. The purpose of this paper is to both critique and provide deeper insight into the TOUS. Origins and Unique Focus Origins of the TOUS focus on the authors’ development of a description of fatigue and dyspnea, and the beginning efforts to document regularities between these concepts. The authors’ relationship first developed when Pugh and Milligan were studying fatigue at two different perinatal phases and united their ideas (Pugh & Milligan, 1995). These ideas were integrated to develop a model of fatigue during the birthing process. The second relationship began when authors Gift and Pugh recognized that their concepts were similar and they identified commonalities between the two symptoms of fatigue and dyspnea (Lenz et al., 1995). After the second relationship was recognized, the work was at the multiple concept level, as it could span more than a single symptom. The formation of a general model that could be extended to multiple symptoms and different clinical populations was on the horizon. In the theory, dyspnea is subjective, as it is only measurable by patient report (Lenz et al., 1995). Lenz et al. (1995) also explains that dyspnea is described similarly to pain. This was when the second development was formed, which linked dyspnea and pain together. During the study of fatigue during childbearing, Milligan and Pugh combined their studies of fatigue from the postpartum and intrapartum periods. Both studies showed a similarity of fatigue producing a “snowball” effect (Lenz et al., 1995, p. 8). Gift and Pugh began to see connections between the A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 4 concepts of dyspnea and fatigue. Both symptoms are defined as subjective, acute or chronic, occur during abnormal or normal conditions, and can be exacerbated by or the result of anxiety or depression (Lenz et al., 1995). Consequently, dyspnea and fatigue can affect activities of daily living and social well-being. Here, the basis of the TOUS was created when the studies of fatigue during childbearing and dyspnea and fatigue were combined (Lenz et al., 1995). Clarity and Simplicity While a theory’ utilization may have great potential in the care of individuals, it is useless if it cannot be understood and applied. Theory needs to be constructed in a manner that is easily understood and where its utilization planning can be readily accomplished. Thus, the comprehensiveness of a theory is validated based on whether the theory clearly states the main contents and whether it is easily understood by the readers while avoiding oversimplification (Fawcett, 2005). TOUS accomplishes this task by providing clarity and simplicity in its formation. Clarity is defined as transparency within perception or understanding with “freedom from indistinctness or ambiguity” (Clarity, 2009). The TOUS provides clarity through its consistency of defined concepts and presented explanations. The theory uses the study of dyspnea and fatigue, allowing pain to be an analog, to combine the descriptions of both findings, resulting in a common understanding (Lenz & Pugh, 2003). Barnum suggests that internal and external criticisms need to be defined by theories and that clarity should be located within the theory (Dudley-Brown, 1997). The internal criticisms are composed of “clarity, consistency, adequacy, logical development, and level of theory development” (Dudley-Brown, 1997, p.78). Meleis states that the clarity of a theory is found in the relationship between the structure and function that have a clear and logical progression of A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 5 development (Dudley-Brown, 1997). The TOUS illustrates this logical progression through the researchers’ initial discovery where that their unrelated focus’ of dyspnea and fatigue shared some of the same characteristics. From there, the researchers began to compare study findings and to develop further research to aid in the development of the TOUS. This clear progression of inquiry, research, development, additional research, and then modification based on critics of their peers, validates the clarity of the TOUS. Fawcett, (2005) includes parsimony as a needed criterion for a workable theory. Parsimony is defined as simplicity or frugality with words or actions (Parsimony, 2012). While the written descriptions of the TOUS are evident throughout its format, the authors aided to the simplicity of the theory through working illustrations to show the interactions and flow of the theory. The major concepts of symptoms and performance outcomes, along with the interrelated categories of psychological, physiological, and situational factors provide a framework for the metaparadigms of the TOUS (Lenz & Pugh, 2003). The original version of the TOUS theory provided an illustrated framework which simplified and provided an organization of ideas and concepts (see Figure 1). After revision, the authors of the TOUS supplied an updated version of the TOUS diagram (see Figure 2). While the increased intricacy of the diagram is not to be disputed, it continues to foster a clear and concise understanding of the TOUS while illustrating the multi-dimensional aspects of the theory, and the overlapping domino affects that the symptoms, factors and performance outcomes experience. Therefore, it is not only through the structure of the TOUS, but also through the visual reinforcement provided by the diagrams that this theory demonstrates simplicity. A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 6 Figure 1. Original illustration of the TOUS. Adapted from “The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: An update,” by Lenz, E. R., Pugh, L. C., Milligan, R. A., Gift, A., & Suppe, F., 1997, Advances in Nursing Science, 19(3), 14-27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9055027 Figure 2. The updated TOUS. Adapted from “The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: An update,” by Lenz, E. R., Pugh, L. C., Milligan, R. A., Gift, A., & Suppe, F., 1997, Advances in Nursing Science, 19(3), 14-27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9055027 A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 7 Theory Generation The TOUS has great potential to generate further theories. The theory was developed using information from prior models and continues to be built upon by researchers (Lenz et al., 1997). When the TOUS was first introduced in 1995, “the authors acknowledged that further development of the model and theory was needed to account for the opportunity of experiencing more than one symptom at a time” (Myers, 2009, p. E3). In 1997, the theory was revised to include this criteria and to further develop the ideas that the original TOUS contained. Additionally, more theories could potentially be developed because the TOUS has been verified by multiple different studies. According to Lenz et al. (1997), “several published studies about other symptoms (eg, pain, nausea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms) have yielded findings that are consistent with the theory” (p. 25). Time after time, the TOUS has been proven accurate by studies, and also beneficial to researchers in various clinical areas. Credibility When TOUS began it was directed at two symptoms but has developed into a more general theory. According to Myers (2009): The theory evolved from collaboration among three individual investigators who began work on two concepts that represent unpleasant symptoms. [...] The investigators noted commonalities between the two concepts and subsequently realized that a more general theoretical formulation would be appropriate for describing multiple symptoms [...] across different clinical populations. (p. E3) In addition, “middle-range theories are abstract, yet are at a level of concreteness that provides linkages with research and practice” (Lenz et al., 1997, p. 14). A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS The TOUS has been used by researchers in studies involving various types of diseases and symptoms. Some of these studies include: “...Chemotherapy-Related Changes in Cognitive Function” (Myers, 2009), “Symptom Clusters in Heart Failure” (Jurgens, 2009), and “Symptom Burden in Inflammatory Bowel Disease” (Farrell & Savage, 2010). The fact that several researchers have used the TOUS, and proven it to be useful, in their studies speaks volumes for the theory. Testability The TOUS has been tested in various situations with different patients and symptoms as the focus of the studies. Fawcett (2005) defines testability as being met when “specific instruments or experimental protocols have been developed to observe the theory concepts and statistical techniques are available to measure the assertions made by the proposition” (p. 133). The TOUS exclusively uses patient reported data, divided into areas of symptoms, influencing factors, and performance outcomes (Lenz & Pugh, 2003). Though this data is not observable, it can still be considered testable. This was determined using the three suggested questions on testability from Fawcett. First, the research has been shown to adequately reflect the basis and purpose of the TOUS. Next, the data is collected through patient reports, which provide a picture of the symptoms being experienced, despite not being an observable indicator. Finally, the data collection can provide a measurement of the theory’s claims. For example, while the researchers were unable to observe all of the symptoms of the patient, the data clearly shows whether the patient experiences an improvement or decline in their perception of their health after appropriate interventions were provided. A patient complaining of pain could also show increased anxiety about a new diagnosis. After providing the patient with the suitable care to decrease that anxiety, the researcher would be able to see if the patient reports an increase, 8 A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 9 decrease, or no change in that pain level. It is the change in the patient reported pain level that would be the indicator of the success or failure of the theory. Consequently, the TOUS is testable. Contribution to Nursing The TOUS was utilized by Tyler and Pugh (2009) to observe the relationship between the theory and a bariatric surgery patient. Bariatric surgery patients are an ideal population with which to test the TOUS, since they involve not only management of physical symptoms, but also a steady support group in their home lives. In this study, it was found that the patient initially reported many poor symptoms such as fatigue, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain immediately following surgery. Upon further investigation, the researchers discovered that the patient’s significant other was incarcerated shortly after her surgery, and her mother and sister were not supportive of the procedure as a whole. This culminated in a loss of an environmental support system and an increased amount of stress on the patient and her five children. Using the TOUS, these environmental and psychological factors were identified, and could be successfully addressed. Following the improvement in these two areas, the patient’s physiological symptoms began to resolve (Tyler & Pugh, 2009). In another example, Myers (2009) looked at the relationship between the TOUS and chemotherapy-related changes in cognitive function. This study discussed the symptoms commonly experienced during chemotherapy. Myers felt that the TOUS was successful in describing both the occurrence of symptom clusters as well as the interrelationship between the symptoms and their contributing or situational factors. For example, the author discusses the benefit of the theory to aid in answering whether depression, anxiety, and fatigue contribute to a decline in cognitive function, or vice versa. A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 10 Both of these studies illustrate the value of the TOUS to nursing practice. By taking a generic and multi-symptom view of the patient, the nurse is able to identify psychological or situational factors that may contribute to the manifestation of certain physiological symptoms. In this way, the TOUS is invaluable for nursing practice. Instead of treating all physiological symptoms with additional medications, the nurse is able to develop a holistic plan that targets the root cause of the symptom. In addition to being able to be used retroactively, the nurse is able to use the theory proactively by putting mental health or support systems in place prior to a surgery or hospital stay. An example of this is the use of support groups prior to bariatric surgery, as suggested by Tyler & Pugh (2009). Using the TOUS to help prevent patients from experiencing symptoms initiated or exacerbated by psychological or situational stimuli, nursing can focused on holistic care, health promotion and disease prevention (Chiverton, Votava, & Tortoretti, 2003). Conclusions The TOUS has evolved from a specific theory to a much more general and applicable one. As evidenced by the studies mentioned, the theory has been shown to be successful in providing insight into symptoms in patients with a wide range of diagnoses. The TOUS is presented in a way that is clear and credible, allowing for seamless use in the clinical realm. Along with this clarity, the TOUS provides the nursing profession with methods that ease the severity of symptoms through a holistic approach that benefits the patient on a physical, emotional and mental level. In this way, the TOUS is invaluable to nursing practice. A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 11 References Chiverton, P., Votava, K., & Tortoretti, D. (2003). The future role of nursing in health promotion. American Journal Of Health Promotion, 18(2), 192-194. doi:10.4278/08901171-18.2.192 Clarity. (2009). Dictionary.com. Lexico Publishing Group. Retrieved October, 17, 2012, from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/clarity?s=t Dudley-Brown, S.L. (1997). The evaluation of nursing theory: A method for our madness. International Journal of Nursing Students, 34(1), 76-83. Farrell, D., Savage, E. (2010). Symptom burden in inflammatory bowel disease: Rethinking conceptual and theoretical underpinnings. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(5), 437-442. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01867.x Fawcett, J. (2005). Criteria for evaluation of a theory. Nursing Science Quarterly, 18(2), 131135. doi:10.1177/0894318405274823 Jurgens, C., Moser, D., Armola, R., Carlson, B., Sethares, K., & Riegel, B. (2009). Symptom clusters of heart failure. Research in Nursing and Health, 32(5), 551-560. doi:10.1002/nur.20343 Lenz, E. R. & Pugh, L.C. (2003). The theory of unpleasant symptoms. In M. J. Smith & P.R. Liehr (Eds), Middle range theory for nursing (pp. 69-90). New York: Springer Pub. Lenz, E. R., Pugh, L. C., Milligan, R. A., Gift, A., & Suppe, F. (1997). The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: An update. Advances in Nursing Science, 19(3), 14-27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9055027 A CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY OF UNPLEASANT SYMPTOMS 12 Lenz, E. R., Suppe, F., Gift, A. G., Pugh, L. C., & Milligan, R. A. (1995). Collaborative development of middle-range nursing theories: toward a theory of unpleasant symptoms. Advances in Nursing Science, 17(3), 1-13. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7778887 Myers, J. S. (2009). A comparison of the theory of unpleasant symptoms and the conceptual model of chemotherapy-related changes in cognitive function. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(1), E1-10. doi:10.1188/09.ONF.E1-E10 Parsimony. (2012). Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus (3rd ed.) Philip Lief Group. Retrieved October 19, 2012, from http://thesaurus.com/browse/parsimony Tyler, R., & Pugh, L. (2009). Application of the theory of unpleasant symptoms in bariatric surgery. Bariatric Nursing & Surgical Patient Care, 4(4), 271-276. doi:10.1089/bar.2009.9953