Gr9 Acad A of W due Sep 18 2015

advertisement

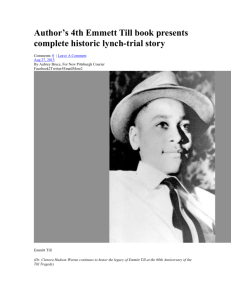

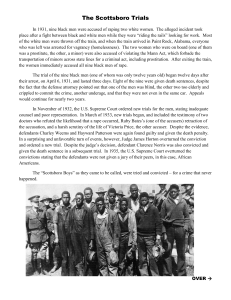

NAME: __________________________________________________________ DATE: ____________________ ARTICLE OF THE WEEK – Academic Ninth Grade DUE ON OR BEFORE FRIDAY, October 2, 2015 Directions: 1. Show evidence of a close read. Mark it up!!! (2 points) 2. Write a 1 page response to this piece on a piece of notebook paper that you will attach to this on a “hot spot” (an idea from the reading that either gets you fired up or gets you thinking) from this article.(6 points) 3. Include a quote from the article in your 1 page response, along with an MLA style parenthetical note. (2 points). 60 years on, Emmett Till's family visits the site of his "crime" and death MONEY, Miss. — Two vans, escorted by local sheriff's deputies, traveled deep into the Mississippi Delta. Through endless stretches of corn and cotton. It was early afternoon when they arrived at the dilapidated grocery store. "Is this it?" one of the travelers asked. The building was barely standing, covered in thick weeds and ivy. Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market, once the centerpiece of Money, a bustling town of 400. In 1955, it was the site of 14-year-old Emmett Till's fatal crime — whistling at a white woman. Today, Bryant's Grocery is deserted and forgotten, much like the town. Although Emmett's murder is considered to have helped spark the civil rights movement, there is little here to recall those events other than a modest historic marker erected outside Bryant's four years ago. Some say the grocery store should be turned into a museum or at least prevented from falling down. "They should have preserved all of it," Eddie Carthan said. He is a distant relative of Emmett's mother and the former mayor of Tchula, which in the 1970s became one of the first Delta-area towns to elect a black mayor. Visitors See A Very Different Town Once wealthy from corn and cotton, towns in this part of Mississippi are now marked by blocks of boarded-up buildings, poor people and stray dogs. "This is one of the poorest areas in the United States of America," said Johnny Thomas, mayor of Glendora, a nearby village. Last weekend, on the 60th anniversary of Emmett's death, some distant relatives decided to visit Money. The visit comes at a time when the nation is wrestling with how to handle public symbols from that era and from other dark moments in the country's past. In recent months, several colleges have taken steps toward removing Civil War statues of Confederate generals. Following the lead of lawmakers in South Carolina, Mississippi officials are considering whether to remove Confederate images from the state's flag. Old And Young Remember Together Among the oldest of Emmett's relatives was Charles Kelly, 66, a second-cousin who said he had played with Emmett just days before he died. Among the youngest was an 11-year-old boy, named Emmett Louis Till Marshall. The family members viewed a documentary about the lynching, one of the most recent in United States history, and marched through the black neighborhoods of Jackson, in a parade in Emmett's honor. They visited Bryant's Grocery store, the shed where Emmett was killed and the river where his body was found. They also visited the courtroom where the men accused of his murder were declared not guilty. A Time Of Deadly Unrest In The South In 1955, the Mississippi Delta was a place where most white people had very different racial attitudes toward black people, FBI investigators wrote in a 2006 report on Emmett's death. Jim Crow Laws that discriminated against black people were widespread. States across the South were locked in bitter battles over the rights of black adults to vote and black children to attend school with white children. White Southerners felt that their way of life was threatened. Poor whites, including shopkeepers who served even poorer black communities, believed racial equality would come at their expense. In Mississippi, the unrest turned deadly. In May 1955, George W. Lee, a black minister who was among the first black residents in the state to register to vote, was shot and killed. That following August, Lamar Smith, a black voting rights activist, was shot to death as he signed up black voters outside a Mississippi courthouse. No one was charged in either killing. Fatal Trip To The Store Two weeks later, Emmett arrived in Mississippi from Chicago for a two-week visit with his mother's family. After a few days, he went to Bryant's Grocery to buy bubblegum. Some people said he whistled at Carolyn Bryant, the wife of Roy Bryant, the store's owner. According to testimony in court, Carolyn Bryant told her husband the next day that Emmett had whistled at her. Roy Bryant was outraged, and the following evening, he and his half-brother kidnapped Emmett at gunpoint. The boy's naked body was pulled from the muddy waters of the Tallahatchie River three days later. The two men claimed they had released Emmett after kidnapping him. They were tried and found not guilty by a jury of 12 white men. State Senator David Jordan, 81, recalled attending the trial as a teenager. The most shocking thing about it, Jordan said, was seeing white reporters from out of town at black businesses. "It was the first time I had ever seen racial integration," said Jordan, who is black. "There were all of these white people staying in the black hotel. I couldn't believe it." "I'm So Sorry" As the sun set, the group visited the shed at the Mississippi plantation, where historians believe Emmett was killed. "I haven't been back in these counties in decades, not since the late '60s," said Kelly, who wore a T-shirt covered with photos of Emmett. "To come back, it's hard. It brings back a lot of old memories that I had forgotten about what this did to our family." "I'm so sorry, Emmett. I'm so sorry," whispered Deborah Watts, a distant relative who co-founded the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation. She held her hands together near her chest as tears spilled from beneath her sunglasses. "I'm so sorry." "He knows you are," her daughter, Teri Watts, said while wrapping her arm around her mother's shoulder. They stood in the shed for several minutes longer, their eyes focused on the wooden rafters where Emmett's body had once hung. "He knows we are," the daughter said. Lowery, Wesley. Washington Post via Newsela (Ed. Newsela staff. Version 1100). "60 Years On, Emmett Till's Family Visits the Site of His "crime" and Death." Newsela. 14 Sept. 2015. Web. 28 Sept. 2015. <https://newsela.com/articles/emmetttill-anniversary/id/11963/>.