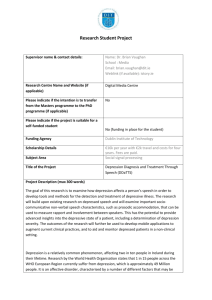

clinical characteristics of depression

advertisement

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND DIAGNOSIS OF DEPRESSION To read up on the clinical characteristics and the diagnosis of depression, refer to pages 425–431 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself How is clinical depression different from feeling “down”? What are the symptoms of depression? Why do you think twice as many women as men are diagnosed with depression? What you need to know CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DEPRESSION The physical and psychological symptoms of depression including physical/behavioural, perceptual, cognitive, motivational, social, and emotional ISSUES SURROUNDING THE CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF DEPRESSION In particular you must consider the issues of reliability and validity Further issues you may consider are: culture bias; social issues such as public and political attitudes to abnormality; and the economic implications of diagnosis CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DEPRESSION Mood disorders are characterised by disturbances of affect (mood), which can be in the direction of depression or elation. Mood disorders are distinguished from normal mood variations by the duration and degree of disturbance. Depression is an emotional response that can have physical, behavioural, perceptual, cognitive, motivational, social, and emotional symptoms. Major depression Physical/behavioural symptoms: Appetite is usually reduced, but can increase (comfort eating) and tends to be unhealthy. Sleep disturbances occur. Insomnia tends to be most common with problems in falling asleep and early morning waking. Hypersomnia can also occur, which is excessive sleeping, and may be an attempt to escape reality. Sleep disturbances result in tiredness and feelings of lethargy (loss of energy) or restlessness. Sex drive is usually reduced. Perceptual symptoms: Auditory hallucinations may occur, which are extreme forms of self-critical delusions as the hallucinations often involve voices that are abusive and critical of the depressive. Cognitive symptoms: Depressives have slow, muddled thinking and difficulty in making decisions. Thinking is pessimistic, negative, and in severe cases suicidal. A negative selfconcept can lead to faulty thinking, when the individual is overly critical of him- or herself—this can develop into delusions. Motivational symptoms: Depressives show a lack of interest (apathy) in their appearance, work, home, and others. There is also reduced activity due to their lack of interest and energy. Social symptoms: Depressives usually show social withdrawal because they do not gain pleasure from social interaction and may feel they have nothing to contribute and do not want people to see them in their depressed state. Emotional/mood symptoms: Depressives show low mood, unhappiness, anguish, and are often on the verge of tears. They may experience anhedonia, which refers to a loss of pleasure in activities previously enjoyed. Diurnal mood variations may occur in which the mood changes throughout the day, being particularly low in the morning and improving a little as the day progresses. Classification of Depression DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition; see A2 Level Psychology page 426), which is the American classification system, and ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases), the tenth edition of which was published by the World Health Organization in 1992 (ICD-10; see A2 Level Psychology page 426), are the two most common classification systems. According to DSM-IV, diagnosis of major depression requires an episode of major depression, which means five or more of the physical, perceptual, behavioural, cognitive, social, and emotional symptoms must persist over a minimum period of 2 weeks, with one of the symptoms being depressed mood or loss of pleasure. An individual with 2–4 depressive symptoms may be diagnosed with minor depression but this is less likely to be formally diagnosed. The criteria used in ICD-10 to diagnose a depressive episode are similar to those used in DSM-IV. Severe depressive episodes must include the following symptoms over at least a 2-week period: depressed mood most of the day and nearly every day, loss of interest or pleasure in activities that are generally regarded as pleasurable, and increased fatigue or reduced energy. Other symptoms must also be present. Types of Depression Depression is the main symptom of a range of mood disorders, which include: Major depression (unipolar) Manic depression (bipolar disorder) Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) Postpartum depression (PPD) Major depression can be divided into different types: Endogenous—caused by factors within the person. Reactive—caused by factors external to the person, such as stressful life events; this is the type that people are most likely to experience. Although a useful distinction, this can be difficult to apply as the depression may be due to internal and external factors. In clinical practice a distinction is often made between minor, neurotic illness, and major, psychotic illness. The former is used when there is mood disturbance only and the latter is used when there are also severe cognitive and perceptual distortions, such as delusions and hallucinations. ISSUES SURROUNDING THE CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF DEPRESSION For any diagnostic system to work effectively, it must possess reliability and validity. Reliability means that there is good consistency over time and between different people’s diagnosis of the same patient; known as inter-judge (or interrater) reliability. If diagnosis of depression is valid then patients who are diagnosed as suffering from depression must have the disorder. If a diagnostic system is to be valid, it must also have high reliability. Clearly if a disorder cannot be agreed upon (so low reliability) then all of the different views cannot be correct (so low validity). Whereas a diagnostic system can be reliable but not valid—it can produce consistently wrong diagnoses. In terms of classification, DSM-IV and ICD-10 take a categorical approach, which assumes that all mental disorders are distinct from each other, and that patients can be categorised with a disorder based on their having particular symptoms. However, diagnosing abnormality is not as straightforward as this approach suggests. The categorical system Several factors can reduce the reliability and validity of diagnosis of major depressive disorder (unipolar depression). First, classification systems such as DSM-IV-TR (revised version of DSM-IV in 2000) and ICD-10 are categorical systems. This is an all-or-none approach in which patients are assumed to have the disorder or not. This seems straightforward but using the system in practice is not because a patient who has six symptoms every day for 13 days would not meet the criteria, yet clearly has experienced some depression. Further evidence that the all-or-none system lacks validity is that those who don’t meet the diagnosis of major depressive disorder or minor depressive disorder do still have some form of depression, which may progress to major depression. For example, Horwath et al. (1992, see A2 Level Psychology page 429) found that over 50% of new cases of major depressive disorder (unipolar depression) had previously reported less severe symptoms of depression. Subjectivity of diagnosis Judging whether patients have any given symptom is subjective because they cannot be measured. For example, loss of pleasure in usual activities is a symptom of major depressive disorder, but how much loss of pleasure is needed to qualify? Comorbidity Comorbidity means that a given individual has two or more mental disorders at the same time. For example, many people suffer from both depression and anxiety. This means the diagnostic categories in DSM-IV and ICD-10 are not distinct from each other, yet the classification systems assume that they are. EVALUATION Different forms of comorbidity mean it is difficult to make comparisons between patients. It is also difficult for the therapist to know which disorder to focus on first in treatment. Diagnosis: Semi-structured interviews Patients are generally diagnosed on the basis of one or more interviews with a therapist. Some interviews are very unstructured and informal. This can produce good rapport between the patient and the therapist, but reliability and validity of diagnosis tend to be low (Hopko et al., 2004, see A2 Level Psychology page 430). The most reliable and valid approach involves the use of semi-structured interviews in which patients are asked a largely predetermined series of questions. EVALUATION Semi-structured interviews do have good reliability and validity. Two of the most used semi-structured interviews for depression are the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Patient Version (SCID-I/P) and the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV). Both interviews involve systematic questioning about a range of symptoms common to depression. High reliability and accuracy. Inter-judge reliability and diagnostic accuracy were both high with the SCID-I/P (Ventura et al., 1998, see A2 Level Psychology page 430). Good reliability when used to assess depression but less so for other anxiety disorders. ADIS-IV is mainly designed to diagnose anxiety disorders. But it also provides an assessment of depression because many patients suffer with both. Brown et al. (2001, see A2 Level Psychology page 430) found good inter-judge reliability when two therapists used ADIS-IV to assess depression (i.e. the two therapists showed good agreement). However, reliability was somewhat lower than for most of the anxiety disorders. Different diagnoses and the “threshold issue”. This lack of reliability was mainly due to patients reporting different symptoms during the two interviews. However, there were also different diagnoses where one therapist diagnosed depression and the other anxiety. The “threshold issue” also reduces reliability because therapists sometimes disagreed as to whether the symptoms exceeded the threshold; we considered this earlier in terms of how much loss of pleasure the patient must show. Content validity Content validity refers to the extent to which an assessment procedure obtains detailed relevant information. Thus, the diagnostic interviews have content validity if they provide detailed information regarding all of the symptoms of depression. EVALUATION Semi-structured interviews can have high content validity. SCID-I/P and ADIS-IV are clearly both high in content validity. Criterion validity Any form of assessment for depression possesses good criterion validity if those diagnosed as having depression differ in predictable ways from those not diagnosed with depression. EVALUATION Evidence for differences. There is evidence that patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder are less likely to be in a long-lasting relationship, to have a full-time job, or to have many friends (Hammen, 1997, see A2 Level Psychology page 431). Difficult to distinguish depression from other mental disorders. This provides some evidence for criterion validity, but note that poor social and work functioning are found in those suffering from most mental disorders and so this doesn’t distinguish patients with depression from patients with other mental disorders. Construct validity Third, there is construct validity, which is the extent to which hypotheses about a given disorder are supported by the evidence. EVALUATION Evidence for depression being associated with a lack of involvement in pleasurable activities. It is often assumed that depression is associated with a lack of involvement in pleasurable activities, and the evidence supports that assumption (Lewinsohn et al., 1992, see A2 Level Psychology page 431). Low levels of serotonin. Similarly, one hypothesis is that low levels of serotonin are linked to depression and so the fact individuals with depression have low levels of serotonin provides some evidence for construct validity. Gender bias Females are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with depression. Some suggest this is due to gender bias—that females are being stereotyped as neurotic, and so more likely to be diagnosed than male patients who present with the same symptoms. However, there are a number of arguments against this—see the section on socio-cultural explanations in Psychological Explanations of Depression for these arguments (see A2 Level Psychology pages 448–449). So what does this mean? Overall, then, it seems that the main ways of diagnosing major depressive disorder possess reasonable content, criterion, and construct validity. The many forms of depression inevitably raise some issues of reliability and validity in diagnosis. The two main systems of diagnosis, DSM-IV and ICD-10, have reasonably good content validity as the research findings suggest they have sufficient detail of symptoms for accurate diagnosis. However, there are many issues that question the reliability and validity of diagnosis, such as the categorical approach, the subjectivity of diagnosis, and comorbidity. Unstructured clinical interviews can lack reliability and validity. However, the semi-structured interviews, SCID-I/P, and ADIS-IV have been found to have reliability as two therapists’ diagnoses have been found to be high in consistency, and they have high diagnostic accuracy (validity). Over to you 1. Outline the clinical characteristics of depression. (5 marks) 2. Discuss the issues associated with the classification and diagnosis of depression. (20 marks)