Title: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Voluntary Core

advertisement

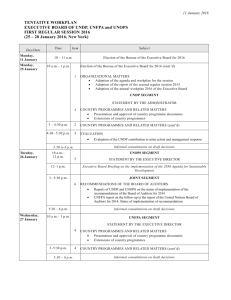

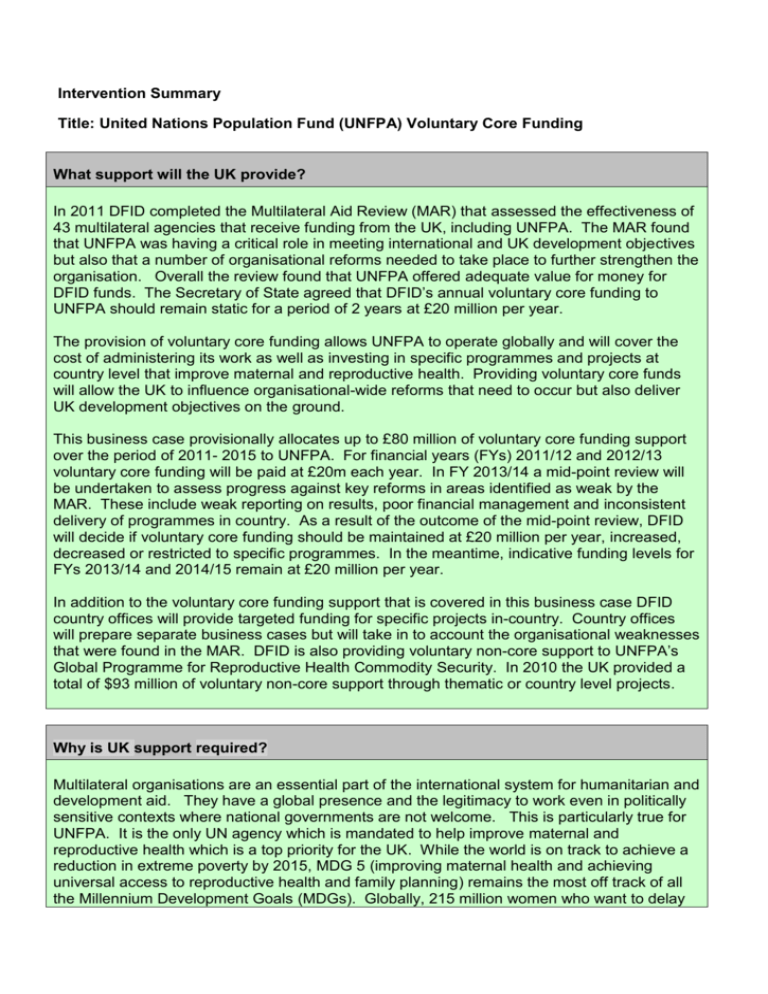

Intervention Summary Title: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Voluntary Core Funding What support will the UK provide? In 2011 DFID completed the Multilateral Aid Review (MAR) that assessed the effectiveness of 43 multilateral agencies that receive funding from the UK, including UNFPA. The MAR found that UNFPA was having a critical role in meeting international and UK development objectives but also that a number of organisational reforms needed to take place to further strengthen the organisation. Overall the review found that UNFPA offered adequate value for money for DFID funds. The Secretary of State agreed that DFID’s annual voluntary core funding to UNFPA should remain static for a period of 2 years at £20 million per year. The provision of voluntary core funding allows UNFPA to operate globally and will cover the cost of administering its work as well as investing in specific programmes and projects at country level that improve maternal and reproductive health. Providing voluntary core funds will allow the UK to influence organisational-wide reforms that need to occur but also deliver UK development objectives on the ground. This business case provisionally allocates up to £80 million of voluntary core funding support over the period of 2011- 2015 to UNFPA. For financial years (FYs) 2011/12 and 2012/13 voluntary core funding will be paid at £20m each year. In FY 2013/14 a mid-point review will be undertaken to assess progress against key reforms in areas identified as weak by the MAR. These include weak reporting on results, poor financial management and inconsistent delivery of programmes in country. As a result of the outcome of the mid-point review, DFID will decide if voluntary core funding should be maintained at £20 million per year, increased, decreased or restricted to specific programmes. In the meantime, indicative funding levels for FYs 2013/14 and 2014/15 remain at £20 million per year. In addition to the voluntary core funding support that is covered in this business case DFID country offices will provide targeted funding for specific projects in-country. Country offices will prepare separate business cases but will take in to account the organisational weaknesses that were found in the MAR. DFID is also providing voluntary non-core support to UNFPA’s Global Programme for Reproductive Health Commodity Security. In 2010 the UK provided a total of $93 million of voluntary non-core support through thematic or country level projects. Why is UK support required? Multilateral organisations are an essential part of the international system for humanitarian and development aid. They have a global presence and the legitimacy to work even in politically sensitive contexts where national governments are not welcome. This is particularly true for UNFPA. It is the only UN agency which is mandated to help improve maternal and reproductive health which is a top priority for the UK. While the world is on track to achieve a reduction in extreme poverty by 2015, MDG 5 (improving maternal health and achieving universal access to reproductive health and family planning) remains the most off track of all the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Globally, 215 million women who want to delay or avoid a pregnancy are not using an effective method of family planning. Each year there are 75 million unintended pregnancies and an estimated 21.6 million of these, nearly all in developing countries, end in unsafe abortion causing the deaths of 47,000 women and adolescent girls – 13% of all maternal mortality. Adolescent girls are particularly at risk. They are less likely to be able to choose whether and when to have a child than older women and have a much higher unmet need for family planning. Globally, there are 6.1 million unintended pregnancies each year among 15-19 year olds and in Africa half of all maternal deaths from unsafe abortion are in women under the age of 25. UNFPA works to tackle these issues that are of critical importance to the UK by advocating for laws to be passed to improve women and girls reproductive rights, supporting the provision of family planning services and by monitoring population trends. The UK will maintain voluntary core funding to UNFPA as its objectives have a direct link to Millennium Development Goals, in particular making progress on MDG 3 (reduce child mortality), MDG 5 (improve maternal health and achieve universal access to reproductive health and family planning) and MDG 6 (combat HIV and AIDS, malaria and other diseases). What are the expected results? Through this voluntary core contribution DFID expects to see UNFPA make progress against the key reform priorities identified through the MAR. In particular the provision of this funding will support UNFPA to: further develop its managing, monitoring and reporting on results, so it can demonstrate the difference it is making on the ground; demonstrate how it is driving down costs and achieving better value for money; strengthen its delivery in country to improve access to family planning, increase recourse to address unsafe abortion and to enable the collection, analysis and use of population data for progressive policy development; improve its financial management compliance and address all outstanding audit issues; increase transparency, so that it meets the International Aid Transparency Initiative’s (IATI) transparency standards. In terms of development results, at the end of the 4 year funding period, DFID expects UNFPA to be able to show evidence of progress being made against MDG 5, particularly in terms of improving access to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR); a reduction in the number of women dying either while pregnant or during child birth; and, an increase in the availability of modern contraceptives to more women. UNFPA’s results reporting framework is currently weak. Therefore, it is not possible to use UNFPA’s own targets to illustrate how UNFPA is delivering on the ground. Addressing this issue is one of DFID’s top reform priorities. After the mid-point review has been undertaken in FY 2013/14 DFID will revisit the project’s log-frame and, where possible, update this to include UNFPA’s own indicators to illustrate the in-country results that DFID’s voluntary core funds support. In the interim the log-frame will principally track progress against MAR reform priorities. . Business Case for: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Strategic Case A. Context Summary The MAR found that UNFPA has a critical role in making progress on maternal health, family planning, safe abortion and sexual reproductive health and rights – all UK priorities. UNFPA has a unique role in taking these issues forward due to its global presence and unique legitimacy that other actors can not replicate. There are a number of organisational reforms that need to be addressed in the short term. DFID will need to work closely with UNFPA to ensure our reform agenda is taken forward leading to improved delivery on the ground. DFID will need to increase its engagment and influence with UNFPA and ensure that all of its funding supports the reforms agenda to see real change. Background Multilateral organisations are an essential part of the international system for humanitarian and development aid. They have a global presence and the legitimacy to work even in politically sensitive contexts where national governments are not welcome. They provide specialist technical expertise, and deliver aid on a large scale. They offer a wide-range of aid instruments to meet the needs of all countries. They have a legitimacy to lead and coordinate development and humanitarian assistance. They broker international agreements and monitor adherence to them. They develop and share knowledge about what works, and why. UNFPA has a critical role within the multilateral system. Improving sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is critical to the achievement of the MDGs overall and is a priority area for the UK government. A commitment to reducing maternal mortality is set out in the coalition agreement and, in December 2010, the UK set out two strategic priorities to achieve this in the Framework for Results for Improving Reproductive, Maternal and Newborn Health in the Developing World: reducing unintended pregnancies and ensuring that pregnancy and childbirth are safe for mothers and babies. Improving access to family planning is very important to the UK due to the difference this would make to women’s lives. UNFPA is a key partner in delivering this agenda as it is a trusted partner of many governments in developing countries. The benefits of investing in SRHR are far reaching. Globally, meeting the unmet need for family planning alone could avoid around a third of maternal deaths and a fifth of newborn deaths. A woman’s social, economic and other opportunities in life are enhanced by being able to make fertility and other health choices. Preventing pregnancy in young adolescents makes a particularly significant difference to girls’ life chances. Household poverty can be mitigated by improving women’s health and survival. Services and programmes that remove or reduce costs of commodities, care or referrals to poor women can prevent families spiralling into debt. In addition improving access to family planning, together with wider investment in girls’ education and empowerment will, through reduced fertility, slow population growth. Most rapid population growth takes place in the poorest countries, where current fertility rates mean that populations are expected to double or triple by 2050 – increasing vulnerability to climate change and increasing the need for health and education services. UNFPA is the UN agency mandated to lead on SRHR and to support countries in generating and using population data for policies and programmes to reduce poverty. UNFPA is mandated to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV/AIDS, and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. UNFPA works within the internationally agreed framework for population and development to take this agenda forward. UNFPA is managed by the Executive Director (Dr Babatunde Osotimehin) and his senior management team. It has 2,000 staff worldwide, 83% of them are field-based within regional or country offices. Staff costs account for 31% of UNFPA’s total expenditure in 2010. UNFPA is governed by 36 member states of the UN. Member states’ membership of the Executive Board is rotational. The Executive Board meets three times per year to set policy direction and provide oversight. The UK is a member of the governing board for 2011. UNFPA carries out a number of critical roles which other multilateral organisations do not replicate: It works with national governments to ensure that reproductive and maternal health issues are included in public health plans and that budget lines are made available to ensure there is a supply of contraceptive commodities. As a UN agency it is politically neutral and develops close relationships with national governments. This allows UNFPA to undertake work that other bilateral or civil society partners can not. UNFPA works across the maternal and reproductive health agenda and joins up work on the delivery of MDGs 3 (gender equality), 5 (maternal and reproductive health) and 6 (HIV/AIDS). It is the lead agency in the UN system for procurement of reproductive health commodities. It supplies commodities to governments, non-government organisations (NGOs), UNFPA country offices as well as other UN organisations at a significant scale. For example UNFPA is the largest supplier of male condoms to low-income countries and the second largest supplier of female condoms (14m in 2009). Given the large amount of procurement it carries out it is able to supply the commodities at competitive prices. It has a key role in assisting countries to collect data on population dynamics and to analyse and use this for policy development e.g. on climate change and service delivery needs. This is particularly critical given the impact of rapid population growth, especially in urban areas, changing age patterns and migration. The world population will reach 7 billion people in 2011. For every 100 people added to this, 97 are in a less-developed countries. In 2011 UNFPA will help 76 countries conduct censuses. By using the information which is generated by UNFPA-assisted censuses and surveys governments, with UNFPA support, can plan for better education, social and health services among other issues. In carrying out this critical work UNFPA helps to meet the UK priority of giving women and girls more choice, better access to family planning and sexual and reproductive health which will lead to a reduction in maternal mortality and morbidity. UNFPA has a global presence. It has offices in 129 countries and works in about 150, in many of which DFID has no presence on the ground, including some fragile states. UNFPA spends almost 50% of its resources in countries with high absolute poverty such as India, Nigeria and Pakistan. But it also targets resources where there is the highest need and where bilateral donors’ reach is limited (such as Mali or Niger). The UK’s Framework for Results for Improving Reproductive, Maternal and Newborn Health in the Developing World identifies UNFPA as an important partner in delivering improved maternal and reproductive health world-wide. Its work on sexual and reproductive health and rights is critical and no other UN actors are well-equipped to tackle this issue. Given the critical importance of UNFPA in improving maternal and reproductive health, a UK priority, the global nature of reproductive health needs and the MAR result, the UK needs a strong and effective UNFPA that can deliver results on the ground. Multilateral Aid Review Findings The Multilateral Aid Review (MAR) was commissioned by the DFID Secretary of State to assess the value for money and impact provided by multilateral agencies that receive funding from the UK. The MAR found that UNFPA is critical in meeting both international and key UK objectives set out by the coalition government, but also that UNFPA’s performance needs to improve in a number of areas. Overall UNFPA was judged to offer adequate value for money for DFID aid funds. UNFPA’s strengths are: its strong partnerships with national governments, civil society organisations and other multilateral organisations; its leadership role in taking forward better joint UN working such as “Delivering as One”, the “Health 4 initiative” (a partnership between UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO and World Bank) and the “Health 8 initiative” (the Health 4 plus UNAIDS, the Gates Foundation, and the GAVI Alliance and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria). Areas were UNFPA’s performance needs to improve are: Better delivery in-country. UNFPA’s performance in-country is mixed. It needs to strengthen this by ensuring it has the right staff in place with the necessary skills and competences. Country office staff must also provide stronger and more strategic leadership, including a willingness to engage on contentious issues such as high mortality and morbidity due to unsafe abortion; Focus on key SRHR issues. UNFPA should focus on its comparative advantage such as family planning, commodity security, safe abortion and access for adolescents to contraceptives rather than on areas where other actors are better placed e.g. skilled birth attendance; Improve its financial management. Its last two audits for 2006/7 and 2008/9 have identified specific weaknesses in UNFPA projects that are delivered through national partners. UNFPA has instigated a number of actions to improve this. Improve its reporting on results so UNFPA can better manage its programmes and also demonstrate the results it directly delivers and how these contribute to wider development outcomes. It is actively working with member states to look for ways to improve in this area. UNFPA’s senior management has indicated a clear willingness to reform and improve its performance in the above areas. It has delivered organisational improvements over the last 10 years such as a new human resource strategy to improve staff performance and establishing 3 regional offices to provide better support to country offices. It is expected that UNFPA will continue make progress on reforms. The new Executive Director (Dr Babatunde Osotimehin - who took up post on 1 January 2011) has already indicated that he will take forward necessary reforms. His reform agenda is closely aligned with the issues identified by the MAR. Continued support and engagement by the UK is critical to ensure UNFPA implements these reforms and delivers a stronger performance overall. UNFPA is a relatively small multilateral organisation. The Table 1 shows UNFPA’s income for the period 2007 – 2010. Table 2 illustrates the UK’s voluntary core funding in US dollar terms compared to other donors. Table 1: Income (millions of US$) Voluntary core income Voluntary noncore income Total 2007 419 2008 428.8 2009 469.4 2010 491.2 286.2 705.2 366.1 794.9 289.6 759 359.3 850.5 Table 2: Top 7 donors in 2010 (voluntary core funding, millions of US$) 1 The Netherlands 2 Sweden 3 Norway 4 USA 5 Denmark 6 Finland 7 UK $73 $60 $54 $51 $37 $33 $30 Voluntary core resources are used to cover administrative costs as well as programme costs. In 2010 total expenditure was $801.4 m of which $683m was used for programme activities and $106.9m was used to cover administrative costs. B. Impact and Outcome Theory of Change Unlike targeted funding voluntary core funding is not tied to a specific project or programme. It supports all of the work of the organisation. The underpinning theory of change is as follows. To deliver better results for women and girls on the ground UNFPA needs to improve its organisational effectiveness, through making the necessary reforms identified in the MAR. We recognise that UN reform can be slow and difficult but this will only succeed through strong engagement with key stakeholders. Implementing real reform will require strong leadership from UNFPA that has the support of the executive board’s membership. DFID is not prepared to accept lower levels of performance from the UN than other multilaterals. DFID will need to do more to ensure we maximise our influence and create new partnerships to support change. We be explicit and clear with UNFPA on the reforms we need to see and use our funding and influence to encourage performance improvements against these organisational-wide reforms. The UK is well-placed to support UNFPA on this reform agenda due to our strong technical focus on results and improved value for money. As a result of stronger engagement and strengthened support leading to reforms being achieved UNFPA’s overall efficiency and effectiveness in-country is expected to improve. This will allow it to deliver better results in the areas of its mandate which are important to the UK (reducing unintended pregnancies, decreasing maternal deaths through averting recourse to unsafe abortion and the generation and use of population data). While much of DFID’s voluntary core funding supports programme delivery, specific country-level results can not be attributed to DFID’s voluntary core funds due to UNFPA’s results reporting system that is currently weak. Impact At the impact level, DFID expects to see progress towards MDG 5, particularly MDG 5b, better access to SRHR. For example, we would want to see an increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate (modern methods) which was 56% in 2003. UNFPA has set a target of 66% for this for 2013 and has also committed to increasing contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) by 2% per year in 45 countries (those supported by the Global Programme for Reproductive Health Supplies). Other key impact indicators are set out in the log frame for this programme. Outcome To achieve this impact we would expect, at the outcome level, to see improvements in UNFPA’s organisational efficiency and effectiveness particularly against the MAR criteria in the areas where UNFPA’s performance was found to be weak. By 2015, UNFPA should be performing satisfactorily in all of these areas. Specific Deliverables and DFID Activities In order to deliver on the above DFID will: Link all of our voluntary core funding set out in this business case to progress against key MAR reforms and be prepared to make cuts if reforms stall. Maintain an in-depth institutional analysis of UNFPA to ensure DFID understands how the organisation operates, how decisions are made, how it is affected by external factors and the progress it is making against key reforms. Develop a comprehensive stakeholder analysis, so that the UK is able to apply our staff resources towards the levers and partners which will help leverage the maximum change. A first stage of this analytical work will be completed by October 2011. Additional follow up work is likely to be required. UNFPA needs to: improve its monitoring and reporting of results. We would expect to see its next Strategic Plan (covering the period 2014 onwards) monitored by a results framework with a clear results chain. This should contain results at all levels, including output (what it delivers) and outcomes (what its outputs contribute to) as well as clear indicators (used to measure these results) and targets (that show the expected level of change). UNFPA annual reports should then systematically report against the indicators and targets included. DFID will work with UNFPA to take substantial steps in this direction through the Mid-Term Review of their current Strategic Plan, taking place during 2011. These improvements would allow UNFPA to better manage their own programme and make evidence based decisions. It would also allow DFID to better attribute areas of success to UNFPA and show the UK taxpayer how their money is being used to deliver real results on the ground. improve its delivery of priority programmes in country, specifically in its key focus areas of population and development, sexual and reproductive health and rights. We want to see UNFPA more focussed on these areas of its strategic and comparative advantage. We will want to see UNFPA providing strong technical and policy leadership on these issues – including using its influence to improve access to safe abortion in line with international agreements. UNFPA should also work in-country to increase contraceptive use, especially for adolescents, reduce the number of stockouts of key contraceptives and improve supply chains. We will also want to ensure that UNFPA does not use its resources disproportionately in areas where others are better placed to deliver or have greater expertise (e.g. skilled birth attendance). These improvements would ensure that UNFPA can better deliver services in-country, through better more strategic dialogue with governments so ensuring that more women and adolescents have access to modern contraceptives and better maternal health services, which in turn would reduce maternal mortality. improve its financial management to ensure UNFPA can account for all of its expenditure. Most importantly UNFPA must implement all outstanding recommendations from the last audit report and put in place mechanisms and strategies to ensure that projects that are delivered through national partners are appropriately audited on time. demonstrate how it is driving down costs and achieving value for money through its results frameworks and reports to the Board. By having a robust results framework UNFPA will be better able to demonstrate how it is achieving value for money – what it is actually achieving with its voluntary core funding. By reducing costs UNFPA will be able to move funding away from administrative areas and concentrate more resources on UNFPA’s programme delivery. increase the transparency of its programme and on how voluntary core and non-core funds are spent. DFID will encourage UNFPA to sign up to the International Aid Transparency Initiative and publish all information on the quality of the projects it funds. These steps will ensure that DFID can show the UK public where their money is being spent, how effectively it is being used and what results it delivers but also most critically reduce the number of women and girls that die during child birth, increase access the family planning and improve the sexual rights of women girls. Consequences of Decreasing or Not Funding If DFID stopped providing, or significantly reduced, its voluntary core funding now we would lose our ability to influence UNFPA on the above MAR reforms across the organisation and also reduce the number of women and girls that benefit from UNFPA’s work. Stopping our voluntary non-core funds would potentially reduce the number of programmes in developing countries that in turn would impact on UK development objectives. Changing the volume of our voluntary core funding is an option at the mid-point review in 2013. In the meantime, because of the importance of UNFPA to UK aid objectives, we need to work with it to strengthen its performance over the next two years. If its performance does not improve we will consider cutting our voluntary core funding and provide voluntary non-core funding to areas or countries where UNFPA is effective to ensure that progress is made on the maternal and reproductive health agenda and UK development objectives. Appraisal Case A. Determining Critical Success Criteria (CSC) Each CSC is weighted 1 to 5, where 1 is least important and 5 most important based on the relative importance of each criteria to the success of the intervention. The logical framework for this programme outlines our key progress monitoring indicators. These critical success criteria set out the conditions and assumptions which need to be fulfilled in order for the outcomes and impact documented in the log frame to be achieved. The CSC is built around the specific areas where weaknesses were identified in the MAR. These are areas where UNFPA must show evidence of improvement if they are to show better value for money at the mid point review. CSC for Description Results/Reforms 1 UNFPA’s Executive Director and senior management team and board members support and implement the organisational-wide reforms that have been identified in the MAR. 2 UNFPA staff in-country provide much better leadership and demonstrate policy influence on key SRHR issues including family planning programming, commodity security and safe/unsafe abortion. 3 Organisational reforms are enacted to allow UNFPA to continue to be seen as an effective organisation. Priority areas are: i) Its next strategic plan (due in 2013) demonstrates priority setting and focus on key areas of SRHR where UNFPA has a comparative advantage and has a robust results framework. ii) It addresses all outstanding audit recommendations. iii) It improves its transparency and meet IATI standards. Weighting (15) 5 5 5 B. Feasible options The MAR has identified the key areas in which UNFPA is operationally and organisationally weak. Our reform agenda is defined by the MAR. There are other areas that UNFPA needs to reform but the selected areas have been prioritised as those which are weakest and which we judge would result in the greatest improvements in UNFPA’s organisational effectiveness and delivery on the ground. The theory of change underpinning this intervention has been outlined in Part B of the Strategic Case. In order to make progress on reforms DFID needs to use our funding to drive forward reforms and increase our influence in the organisation. To achieve this there are two financing options to consider. There are also different approaches to how we can influence the organisation. These are also discussed below. Option 1: Voluntary core funding This type of funding is allocated to an institution (such as UNFPA) but is not tied to a particular theme or project. It can be spent against any activity that relates to UNFPA’s mandate. Option 2: Voluntary non-core funding This type of funding can be allocated against specific projects in country (for example a HIV/AIDS project in Nigeria) or by a particular theme (for example reproductive health commodities security). Once allocated it can not be spent on other issues beyond the scope of the original project or theme. Engagement / Influencing There are two options for engaging with and influencing UNFPA. DFID can simply tell UNFPA the areas where we wish to see reform then reassess its performance in two years’ time, and adjust funding accordingly. This approach would allow DFID to scale down its engagement with UNFPA over the coming two years and invest staff resources elsewhere. Alternatively, DFID can increase its influencing with UNFPA by strengthening officials’ engagement with the agency. This approach would require additional staff resources but would allow DFID to maintain its knowledge base and engagement with the agency. Bearing in mind that UNFPA is critical in achieving the UK's objectives on improving maternal health and achieving universal access to reproductive health and family planning and the complexities of creating change in the UN, the preferred option is to increase our engagement. DFID will work with UNFPA to improve delivery of priority SRHR programmes in country. In order to do this UNFPA need to strengthen its country offices by ensuring that the staff incountry have the relevant expertise and experience to be able to carry out their duties. To support this DFID will work with specific country offices to seek feedback, understand delivery problems at country level and track UNFPA’s progress towards improved delivery. These issues can then be addressed bilaterally with UNFPA or at Board level as appropriate. DFID officials will continue to push for reforms and improvements through the Executive Board which meets 3 times a year. Officials will work directly with other like-minded donor countries to build alliances around our reform priorities. This will be done through bilateral meetings between UNCD officials, including at head of department level, and counterparts in other countries. We will also look for opportunities to engage with UNFPA staff, including senior management at ministerial level as and when the opportunity arises. UNCD’s Results Adviser will provide support to UNFPA to assist it in understanding and refining its results management, monitoring and reporting. The introduction of UNFPA’s new results based budgeting model will also offer the opportunity to engage and make progress on the results agenda. C. Appraisal of options Option 1: Voluntary core funding The benefits of this option 1 are DFID will continue to have leverage with the agency and other board members on key reforms that need to occur. The provision of voluntary core support will allow UNFPA to maintain a global presence and operate in countries were DFID can not work, but still have a high need for maternal and reproductive health services. UNFPA can use DFID’s funding to make changes on MAR reforms which will make them more efficient and effective UNFPA programme work will be more sustainable as UNFPA country offices can use voluntary core funding on priority projects. The costs of option 1 are: In the absence of a robust results framework voluntary core funding does not have a direct link to country level results and so DFID’s funding can not be directly attributed to progress against specific development results. DFID will need to maintain a significant policy engagement with UNFPA to ensure these funds are well spent. Cutting DFID’s voluntary core support could undermine the financial viability of UNFPA as it needs a certain level of voluntary core funding in order to operate globally. Reducing or stopping our voluntary core contribution to UNFPA could slow progress on SRHR thereby having a negative effect on achieving UK development objectives. Option 2 – Voluntary non-core funding An alternative would be to target our funding i.e. only provide funding to be used for a specific programme e.g. the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security (GPRHCS). The UK already has specific voluntary non-core funding to this programme, providing £100m over a 4 year period from FY 08/09 to 12/13. The benefits of this option 2 are DFID can target specific programmes or themes which are important to UK development objectives and more robustly measure results. It would potentially allow DFID to reduce its central engagment with UNFPA, The costs of option 2 are: DFID would lose influence in the governing board of UNFPA and have reduced leverage over key reforms that we need to see. As voluntary non-core funding is restrictive it would only allow UNFPA to operate where donors provide adequate support. For example, to target funding only through the GPRHCS would mean that the money can only be spent on that programme, which predominantly works in 45 countries but can also provide emergency funding to additional countries that face stock-outs of commodities. This would mean that UNFPA would not be able to use these resources for programmes elsewhere where needs are still unmet and this would reduce the effectiveness of UNFPA in reaching all of those most in need. D. Comparison of options The same weighting is used as for CSC above. The score ranges from 1-5, where 1 is low contribution and 5 is high contribution, based on the relative contribution to the success of the intervention. Analysis of options against Critical Success Criteria Option 1 Option 2 CSC Weight Score Weighted Score Weighted (1-5) (1-5) Score Score 1 5 5 25 2 10 2 5 2 10 4 20 3 5 5 20 1 5 Totals 55 35 Conclusion Voluntary non-core funding is a useful tool when there is a particular project or theme being funded e.g. the GPRHCS, where we are looking for specific results in an area where UNFPA can bring maximum impact. However, as described above, targeted funds only have limited coverage and cannot cover all of an agency’s mandated areas or work in all countries where there is a need. The MAR found that UNFPA needs to make changes at an organisational level. A provision of voluntary core funding is the best way to support these efforts. However, the provision of voluntary non-core funds (e.g. the GPRHCS or in-country funding) will continue. Voluntary core funding also enables DFID to legitimately promote organisational reforms. Without the voluntary funding it is also arguable that the impact of DFID’s voluntary non-core funding is also reduced In order to ensure that we continue to have influence over the organisation and make progress on reform priorities we will engage more directly with the agency on issues such as strengthening results reporting and improving indicators for outcomes and outputs in the mid term review of the strategic plan. We will also look for opportunities to push our reform issues through statements and decisions at the Executive Board and through direct contacts with the organisation at all levels. We will build stronger relations with other member states who consider that reform is necessary to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of UNFPA and we will look for a stronger relationship with the agency on these issues. The provision of voluntary core funding allows DFID to pursue these objectives. However, if the mid-point review indicates that no progress is being made on our top reform asks DFID will consider changing our approach to funding to continue to ensure maximum value for money for the UK taxpayer. E. Measures to be used or developed to assess value for money DFID will use the same broad criteria to assess the value for money of its voluntary core contribution to UNFPA in two years’ time that were used under the MAR. In FY 2013/14 a further review will be undertaken to assess progress against key reforms areas identified as weak by the MAR, which included weak reporting on results, poor financial management and weak delivery of programmes in country. As a result of the outcome of the mid-point review, DFID will decide if the best value for money can be achieved by continuing voluntary core funding at £20 million per year, increasing this amount, decreasing it and/ or targeting it for specific programmes. In the meantime, indicative funding levels for FY 2013/14 and FY 2014/15 have been made at £20 million per year. Commercial Case A. Value for money through Procurement The MAR found no material weakness in UNFPA’s approach to procurement. However, there are areas where UNFPA needs to continue to improve. DFID will increase its focus on procurement and ask for regular updates on UNFPA’s performance at Executive Board meetings in order to develop a better understanding of the effectiveness of UNFPA’s procurement work. UNFPA has no overall strategy for procurement but it does have procedures that are regularly reviewed and updated, either annually or biannually and procurement policies are available to all Country Offices along with guidelines on developing country procurement plans. UNFPA procurement policies have been certified as being compliant with best practise by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO); this certification is renewed annually. UNFPA is the only UN agency with this certification. UNFPA does not have a specific policy on achieving savings nor are its offices and staff required to achieve specific efficiency savings from procurement. UNFPA does ensure that contracts are tendered for using standard UN terms. In terms of staff, UNFPA’s procurement staff undertake a week-long introductory training course with further one or two week workshops on Enterprise Resource Systems. Procurement staff also need to disclose their financial situation. UNFPA has a good record in commodity pricing and quality. The Procurement Services Branch (PSB) has recently introduced a new procurement initiative called ‘Access RH’ which aims to shorten supply chains and drive cost efficiencies by pooling purchase orders of partner governments and other stakeholders. It will facilitate the supply of quality, affordable reproductive health commodities and reduce delivery times for clients in over 140 developing countries. This initiative went live in February 2011 and it has recently filled its first order for condoms to Mongolia. While it is too early to say how successful this initiative will be previous experience on sharing intelligence on pricing with USAID and others had driven price reductions. As a provider of voluntary core funding to UNFPA and one of the main donors to the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security (GPRHCS), which has overall responsibility for Access RH, DFID has a keen interest in the success of this initiative. Supporting the successful implementation of ‘Access RH’ is our primary objective and opportunity for ensuring more effective UNFPA procurement over the period covered by this business case. We will increase our engagement on this at the Board. UNFPA spent $209 million in 2010 on projects that are delivered by national partners corresponding to over 2,300 projects delivered by over 1,295 implementing partners at 132 country and regional offices and headquarters units. Ensuring that UNFPA achieves value for money and adequate oversight of this “national execution” spending is a top priority, which we will pursue primarily through our interventions in the Board. Financial Case A. How much it will cost Voluntary core funding will be £20m per year for each of FY 2011/12 and 2012/13. In 2013 DFID will review progress against the MAR reform priorities and Ministers will take a decision as to whether funding should remain the same, increase, decrease or be targeted against specific projects/programmes. Pending that review a further £20 million has been provisionally set aside for each of FY 2013/14 and 2014/15. B. How it will be funded: capital/programme/admin The funding will be paid from DFID’s programme budget. C. How funds will be paid out The £20 million allocation for FY 2011/12 and 2012/13 will be released in two payments of £10 million, this reduces the possibility of paying in advance of need. For FY 2011/12 DFID will make the two £10 million payments in August and November. In FY 2012/13 the payments will be made in April and September to provide funding more evenly in the UN’s financial (calendar) year. By September 2013 the mid-point review will have been completed. DFID will release funding for FY 2013/14 by October. For FY 2014/15 payments will be made in April and September. The timing of payments will be set out in a Memorandum of Understanding between DFID and UNFPA. To ensure no payment in advance of need DFID will monitor UNFPA’s balance of voluntary core resources. In 2009 UNFPA’s cash balance was $19.1m, which is acceptable as a reserve, representing 4% of voluntary core funding resources for that year. We will continue to monitor this annually. D. How expenditure will be monitored, reported, and accounted for UNFPA’s expenditure is monitored through the UK’s engagement at Executive Board meetings and bilaterally with UNFPA, as required. These functions are carried out by both officials in the UK and also at the UK’s Mission to the UN in New York. UNFPA provides a range of reports to the Executive Board that DFID uses to monitor its performance. The main reports are: The Executive Director’s annual report: Provides an overview on the results UNFPA has achieved over the year. The Statistical and Financial report. Provides details of all income and expenditure in the calendar year, including details of fund balances and reserves held at the end of the financial year. Expenditure is initially broken down between expenditure on programmes and projects and expenditure on administration/management. The overall programme expenditure is then further broken down to show spend by region, activities, including procurement, and into the 3 programme areas from its mandate i.e. reproductive health, population and development and gender equality. This allows the UK to see how UNFPA’s voluntary core funds have been spent. The annual internal audit and biennial evaluation reports: Provide an overview of UNFPA’s programmatic performance, the risks facing the organisation and the steps that are needed to address any weaknesses. DFID’s voluntary core funding financial contribution is accounted for through the biennial set of certified accounts that are completed by the UN’s Board of Auditors (BoA). The BoA’s report provides an opinion on the financial integrity of the organisation. Management Case A. Oversight Governance arrangements UNFPA’s Executive Board consists of 36 UN member states that are elected for three-year terms; 12 donors and 24 programme countries sit on the Executive Board and each member has equal voice and voting rights. Non-board members can also participate in board sessions to express their views but do not have voting rights. All Executive Board meetings are held in public, unless the board determines otherwise. The UK is a board member until the end of 2011 and will resume its membership in 2013 for three years. The Board provides strategic policy advice and oversight to management and takes decisions on papers and documents that are presented. The Board aims to take decisions by consensus. If countries have serious concerns with UNFPA’s operations these are usually raised through bilateral contacts with the UNFPA Executive Director. All governing board meetings are held in public, unless the board determines otherwise. Intergovernmental organisations and non-governmental organisations can participate in executive board meetings but have to be accredited to the UN and formally invited by the board. Oversight in UNFPA UNFPA’s accountability system broadly conforms to National Audit Office standards i.e. it has an independent internal auditor, an independent external auditor and an independent Audit Advisory Committee. Internal audit is carried out by the Department of Oversight Services (DOS) under the oversight of its Director. UNFPA’s external auditor is the UN Board of Auditors that provides a certified set of accounts every two years – in line with all UN agencies. The Audit Advisory Committee is made up of 5 independent members who provide advice to management on the risks facing the agency. The DOS reports to the Executive Board annually on internal audit and oversight issues. It is the responsibility of DOS to assess if UNFPA is working in an effective manner and complying with its financial regulations and controls. Oversight by DOS includes internal audits and fraud detection and investigation. The DOS also monitors progress against recommendations made by the Board of Auditors. The UN Board of Auditors is responsible for certifying UNFPA’s financial statements. The UK’s National Audit Office is currently the member of the Panel of Auditors that assesses UNFPA and will certify UNFPA’s next set of accounts for 2010 and 2011. The BoA provides a comprehensive report to the board that covers both compliance and value for money. The Audit Advisory Committee is responsible for assisting the Executive Director in carrying out their oversight responsibilities. It also provides an annual report to the Executive Board on the major strategic oversight issues facing the organisation. Reports from all three parts of UNFPA’s oversight machinery are presented to the Executive Board with management responses from the Executive Director. These reports provide an update on the implementation of any audit recommendations and an overview of the risks facing the organisation. All of these reports are available on the UNFPA website. Executive Board members can comment on the reports and make suggestions to UNFPA which will help to improve and strengthen its audit. The UK actively participates in the Executive Board meetings and raises issues of concern. B. Management DFID staff exercise due diligence in oversight of UNFPA’s activities. Board documents and reports are scrutinised to ensure that funds are spent efficiently and effectively to maximise the impact of UNFPA’s work. DFID has adequate staff resources to provide proportionate management and oversight of UK taxpayers’ funds. The team responsible for relations and oversight with UNFPA will be led by an A2 Team Leader in DFID’s United Nations and Commonwealth Department (UNCD). The team leader is also responsible for 2 other agencies, WHO and UNAIDS, as well as UN system-wide issues. All programme management, including project reviews and payments will be the responsibility of a dedicated B1 Deputy Programme Manager. All programme management activities will be carried out in accordance with the DFID oversight requirements. The Team Leader or the DPM will support UKMis in representing the UK during Executive Board meetings. The UK Mission to the UN (UKMIS) in New York is the focal point for engagement with UNFPA. UKMIS will take the lead on issues where discussions are sensitive and a face-toface meeting is required to ensure appropriate oversight. UNCD’s A1 governance adviser and A2 results adviser will provide policy advice on the appropriateness and effectiveness of UNFPA’s governance arrangements and results systems. DFID’s Internal Audit Department will provide advice on key financial papers that are presented to the Executive Board. Procurement department will also provide advice and guidance on procurement issues as necessary. Technical inputs will be provided by a Health Adviser in Policy Division. Policy Division will also assist UNCD when information is being gathered from the in-country offices through providing details of overseas health advisers and providing guidance on technical questions to be used to draw out the most relevant information for further assessment purposes. UNCD will also use contacts with a range of DFID and other member state country offices to improve the feedback on UNFPA’s performance in country. C. Conditionality The level of funding for the outer 2 years will be dependent on progress being made against the reform agenda which was set out in the MAR. If there is little or no progress further consideration will be required as to whether funding should be decreased or restricted for use against specific projects/programmes. E. Monitoring and Evaluation As part of this business case DFID has developed a logical framework (log-frame) which will be used to measure UNFPA’s progress annually. The baseline for reforms in the log-frame will be the results of the MAR. The log-frame shows the high-level goals which have been set and contain indicators (what we will measure), milestones (how the end result will be reached) and targets, (what should be achieved by the end date). The information in the logframe will be reviewed annually to check if progress is being made. The progress will be assessed through information provided by UNFPA in a range of different reports to the Executive Board. We will also seek opinions from the DFID country offices who work directly with UNFPA in-country. This will allow a systematic monitoring of performance at country level. Their views will be incorporated in the reviews. UNFPA is currently undertaking a mid-term review of its Strategic Plan which is due to be completed and presented to the Executive Board in September 2011. The review must result in UNFPA being able to demonstrate its contribution to development outcomes which are critical to UK objectives. DFID are providing support on this exercise through inputs from UNCD’s results adviser. The first annual review will assess UNFPA’s progress against key reforms and if there have been no major events which would knock the reforms off track. At the mid-point a more holistic review will be undertaken that will result in UNFPA’s funding levels being reviewed. UNFPA introduced a new evaluation policy in 2009 but DFID considers this to be relatively weak. Previous audit reports have highlighted this as a recurring issue and this has been raised at the Boards. DFID continues to press for improvements in this through inputs at the boards where we have support from other board members. DFID will not conduct an indepth evaluation of UNFPA’s work but DFID’s Evaluation Department will provide advice on how UNFPA can improve and strengthen its evaluation functions. G. Risk Assessment Risks to UNFPA As a multilateral organisation UNFPA’s country programmes and headquarters units are audited using a risk-based approach. UNFPA’s own internal auditors have identified 3 risks categories that the agency needs to manage. Governance: UNFPA has a unique role but in order to function effectively it must focus on its comparative advantage. It needs to continue to build strong relationships with key stakeholders (partner governments, NGOs, donors) and refocus its work on areas where it matters most. Unless it continues to sharpen its focus it risks reducing its potential impact and results. People: UNFPA has recently further decentralise decision-making to its 129 country offices. 73% of staff are based in-country, with a further 10% in regional centres. However, many critical posts remain vacant for long periods of time. UNFPA faces a risk of managing a large volume of remote entities, with a large percentage of staff in new or reassigned functions without the proper skills and expertise. Programmes: To date UNFPA has not been successful in measuring its global level result but it also has a number of compliance issues to address relating to projects that are delivered through national partners. UNFPA needs to manage the risks to its reputation by addressing outstanding audit issues and strengthening its results systems. Through the UK’s membership of the executive board DFID will track how the organisation is managing these risks and take appropriate action through board decisions and bilateral meetings. Risks to DFID’s reform agenda There are two key risks which could threaten the success of our reform agenda with UNFPA. While these risks could have a high impact on the successful delivery of this intervention, we consider that we can lessen them through continued dialogue and engagement with other donors and UNFPA itself. Other board members block reforms: The UN mostly takes decisions by consensus. There are many other donors and board members who may agree with some of the MAR findings but do not feel as strongly about them as DFID does, in particular on obtaining clear value for money through better results. The risk is that we cannot get others to support our reform objectives. While this is a major risk we will manage this by increasing our engagement with UNFPA and its Board. Senior officials from DFID, including the Head of UNCD, will engage more regularly with other likeminded donors to encourage them to support our reforms. UKMIS will also engage with other influential board members in New York to explain the rationale behind the reforms and encourage their support too. We will also seek opportunities for top management and Ministerial engagement with UNFPA. UNFPA staff are reluctant to change: The new Executive Director accepts the need for reforms, and many of his reform ideas mirror DFID’s, however there is a risk that UNFPA staff will resist change. Reform could therefore stall. To mitigate this risk UKMis will actively engage with UNFPA staff in middle, senior and top level grades to make the case and monitor progress on reforms. This will be carried out through regular meetings led by UKMis staff or further direct engagement by senior DFID officials. F. Results and Benefits Management The logical framework sets out the goal, impact, outcomes and outputs for this business case. The logical framework is based on the reform priorities identified through the MAR and if these are delivered this should lead to better, more efficient performance by the agency at the country level. Milestones have been included where possible to assess if progress is on track. We will revisit the log-frame after the mid point review in 2013 and seek to introduce more targets that relate to UNFPA’s in-country delivery and MAR reform areas. In the interim: Overachievement would constitute UNFPA being judged as a strong performer against the MAR reform areas (results, in-country delivery, financial management, costs control and transparency) and no slippage in all other areas by the mid-point review in 2013. Underachievement would constitute UNFPA being judged to have made no, or limited, progress against the MAR reform areas (results, in-country delivery, financial management, costs control and transparency) by the mid-point review in 2013. DFID will increase our engagement with DFID country offices and other non-focus countries to gather more feedback on UNFPA’s performance in-country. The log-frame is annexed.