Here - The Bahamas National Trust

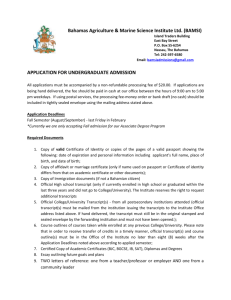

advertisement