here - Theodore Parker Church

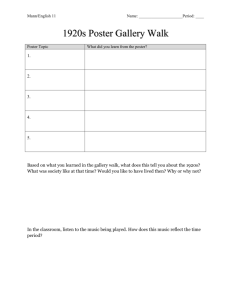

advertisement

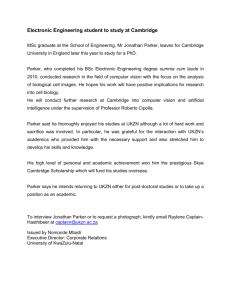

Death and Life of Parker 1 The Death and Life of Theodore Parker May 23, 2010 By Dean Grodzins You are in Florence, Italy, in the summer of 2010. The hotels are full, the shops and restaurants packed, the line to the Uffizi museum is six hours long, and on every corner stand knots of people, in short sleeves, baseball caps and sunglasses, cameras around their necks, puzzling over a map. not among them. You have a mission. Today, you are It is August 24, Theodore Parker’s birthday, and you are going to visit him. You leave your hotel near the Duomo and walk about 20 minutes to the northwest, till you reach the spot where once stood the massive city walls. Just beyond them, in what is now a busy traffic circle, you see a little hill, shaded by cypress trees and spiky with white stones. It is a graveyard for Protestants, built when the laws did not allow them to be buried within the city walls. Florentines call it the “English Cemetery” because the remains of so many British and American travelers lie there. You enter the cemetery through a set of large iron gates. At the small mortuary chapel, an elderly, scholarly Anglican nun in a blue habit greets you and has you sign the visitor’s book. She tells you where to find Parker’s grave. You climb the hill along a path, past rows of bleached monuments, then at the Death and Life of Parker summit, turn right. 2 Ten steps down the slope and there, on your left, in the shade of the trees, is a large, white stone. The inscription honors Theodore Parker as “the great American preacher.” His name, it says, “is engraved in marble, his virtues in the hearts of those he helped to free from slavery and superstition.” August 24, 1810. He was born in Lexington, Massachusetts, on Today, he is 200 years old. He died here in Florence just over 150 years ago, on May 10, 1860. Although he was just 49, he looked much older. His headstone has carved into it a large medallion portrait of a bald and gray-bearded man who could have been 70. Parker had been worn down by overwork before being killed at last by tuberculosis. He had lived intensely. Growing up without money in a family of farmers and largely self-educated, by his twenties he had turned himself not only into a Unitarian minister, but into one the most learned biblical scholars in America. His studies had convinced him that the biblical miracles were myths, that the biblical books were a jumble of texts composed, then rewritten and redacted, by unknown people at different times for diverse purposes, and that no part of the Bible ought to be understood as the infallible word of God. Transcendentalist movement. He came to ally himself with the Along with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Bronson Alcott, he sought Death and Life of Parker 3 divine inspiration not in the Bible, but in the soul and in nature. He always called himself a Christian, however, and kept a bust of Christ on his desk. In 1837, he was ordained here, in West Roxbury, then a tiny parish. Parker’s passionate and eloquent preaching soon attracted attention, however, and in 1841, Parker became the center of an explosive controversy when he preached about The Transient and Permanent in Christianity. In this sermon, he denied the miraculous authority of the Bible and Jesus in strong language. His pronouncement shocked his fellow Unitarians, most of whom denounced him as an infidel. But many others saw in Parker a brave reformer and champion of freedom of speech and thought. In 1845, Parker’s Boston supporters organized a new church for him, which came to be called the Twenty-Eighth Congregational Society; thousands turned out every week to hear him. In January 1846 he was installed as minister there. He was so isolated that he had to preach his own installation sermon. The following month, he preached his farewell sermon to West Roxbury. Over the next 13 years, while continuing to grow his Boston ministry, he became a best-selling writer, a popular lecturer across the North, and the leading intellectual of the antislavery movement. preoccupy him. The slavery issue came increasingly to In 1850, when Congress passed a law establishing a federal fugitive slave-catching bureaucracy, Parker led Death and Life of Parker resistance to the law in Boston. 4 By the end of 1856, he had grown convinced that slavery in America could no longer be ended by conventional political means, and that a civil war was inevitable. In early 1857, during a particularly grueling season of lecturing and preaching, he had suffered a physical collapse. For two months, he was almost entirely confined to his bed. He finally did recover enough to return to work, but he never again felt really well, and in the fall of 1858 he grew rapidly feeble. In October, surgeons came to his house, etherized him, and removed a painful boil. The operation was supposed to cure all his symptoms, but probably only weakened him further. In November, he had a carriage accident that wrenched his groin so badly he could hardly walk. Winter came hard and bitter that year. solid to the horizon. Boston harbor froze By December, Parker rarely left the library on the top floor of his Boston townhouse. His meals were brought to him by dumbwaiter, and he slept on a couch, surrounded by his thousands and thousands of books. Yet he still felt bound to perform his ministerial duties. The morning of January 2, 1859, found him at his preaching desk, where he delivered a sermon on “What Religion May Do for a Man.” On the evening of January 4th, despite a heavy snowstorm, he ventured out again and delivered a lecture to the young men and Death and Life of Parker women of his congregation on “John Adams.” 5 He was prepared to deliver another sermon the following Sunday, as well as a lecture a few days later on “Thomas Jefferson;” both were already written. But in the early hours of Sunday, January 9, his lungs began to bleed. Later that morning, his congregation assembled to hear him. Instead, the chairman of the standing committee rose and read a short note from Parker, scrawled in pencil, saying he could no longer preach. People wept at the news. His doctors soon confirmed he had tuberculosis and told him to get away from the cold weather as soon as possible. In a few hectic weeks he put his affairs in order as best he could. On February 3, he took a train from Boston to New York City, and five days after that he set sail, heading south. He traveled first to the balmy air and warm waters of the Caribbean, where he stopped for a time in Cuba and then the Virgin Islands. When spring came, he crossed the Atlantic and visited England, France, and Switzerland. where he spent the winter. Finally, in October, he reached Rome, With him almost every mile of this voyage were his wife, Lydia, and his longtime assistant and confidante, Hannah Stevenson. Other friends joined them for various periods in Cuba and throughout their stay in Europe. Parker was supposed to be resting, but he had difficulty being idle. Ever since he was a boy, he had risen before sunrise and Death and Life of Parker 6 worked till past midnight, and these were hard habits to break. His voice was now too weak to preach or lecture, but he continued to write. Besides working on an autobiography, which he never finished, he kept a diary and a journal, and composed hundreds of long letters, several of which were published in the Boston newspapers. In early 1859, while in the Virgin Islands, he wrote a 40,000-word letter to his congregation. It was published later that year as a book with the title “Theodore Parker’s Experience as a Minister” and is now regarded as one of the most important confessions of faith produced by the Transcendentalist movement. While abroad, Parker also kept abreast of news from back home. In the summer of 1859, he learned that a meeting of the alumni of the Harvard Divinity School had considered a motion, offered by a few of his friends, extending to him “our earnest hope and prayer for his return, with renewed strength and heart unabated, to the post of duty which he has so long filled with ability and zeal." A majority of the alumni, however, all of them Unitarian ministers, declined to support this resolution. Parker remained a very controversial figure within Unitarianism; Unitarians would not come generally to accept his views for another generation. Parker himself commented that for his fellow ministers’ sake, he would rather they had passed the resolution; for his own sake, it was of no consequence. Death and Life of Parker 7 News of greater consequence for him came some months later. In October 1859, the abolitionist John Brown, backed by a small militia of followers, had attempted to start a slave insurrection by assaulting the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. He failed. Many people had been killed, and Brown himself was captured, tried, and in December hanged. Parker was deeply implicated in the Harper’s Ferry attack, which many historians believe made the civil war between the North and South inevitable. He had met Brown in January 1857, and they had immediately seen eye to eye. Both believed that the Slave Power was on the march, and that only violent resistance could now stop it. In March 1858, Brown revealed to Parker his long- contemplated plan to start a servile war in Virginia. Parker himself was already an advocate of slave uprisings; on his desk, alongside the bust of Jesus, he had placed a small sculpture of Spartacus. Parker joined the so-called Secret Six conspiracy, which provided Brown with gold and weapons. Now, learning that Brown was facing death, Parker wrote a long, public letter defending what Brown had done as a blow for human rights. When the letter arrived in America in December, Parker’s friends immediately put it in print as a pamphlet——his last publication to appear during his lifetime. At various points during 1859, Parker’s health had seemed to be on the mend. In letters, he happily reported every temporary gain of weight and energy. But he never stopped coughing. Death and Life of Parker 8 During the winter in Rome, which was surprisingly cold and wet, his health deteriorated rapidly. By early 1860, he knew he would soon die and so resolved to leave the “eternal city.” He hated its despotic ruler, Pope Pius IX, who was in the process of setting the Catholic Church firmly against democracy and the values of the Enlightenment. In late April 1860, even though Parker was critically ill, he and some companions undertook the trip to Florence. Only months before, Lombardy had come under the control of the King of Sardinia, a constitutional monarch. Parker wanted to die on liberal soil. He arrived in Florence on April 26 and moved into a pension on the south side of the Arno River. With him, besides his wife, were an American doctor, the doctor’s wife, and one of Parker’s closest friends, a Swiss scientist named Edouard Desor; this group was soon joined by Parker’s assistant, Hannah Stevenson, who had been traveling for a few weeks independently, and by an Anglo-Irish woman, the philosopher and feminist Frances Power Cobbe. Cobbe and Parker had never met, but they had corresponded for years, and Parker had overseen the publication of Cobbe’s first book. Cobbe described their first encounter, on April 28, 1860: He was lying in bed with his back to the light. ... He took my hand tenderly and said in a low hurried voice holding it, “After all our wishes to meet, Miss Cobbe, how strange it is we should meet thus.” I pressed his hand, and he turned his eyes, which were trembling painfully and Death and Life of Parker 9 evidently seeing nothing, towards me and said, “You must not think you have seen me. This is not me, only the wreck of the man I was. ... I am not afraid to die,” he smiled as he spoke, “but there was so much to be done.” Parker lived for 12 more days, often sleeping, sometimes awake and delirious, occasionally awake and lucid. day to visit him. his room. Cobbe came twice a On May 10, at midday, she saw him asleep in About 3 o’clock, Desor called on him. Parker, now awake, took his hand, looked at him, and fell again to sleep. Desor left the room; Lydia Parker and Hannah Stevenson sat vigil. At about 4 o’clock, they noticed he had stopped breathing. Parker’s doctor placed the time of death at 3:15. Parker had passed away so quietly, the women had not noticed. In one of his last clear-headed moments, he had asked Desor to arrange a very simple funeral for him. It took place three days later, on May 13, a Sunday, at 4 in the afternoon. At that exact moment, across the ocean in Boston, where it was 10 in the morning, Parker’s huge congregation was gathering to worship. In Florence, only seven people were present: Lydia Parker, Hannah Stevenson, Desor, Cobbe, Parker’s doctor and his wife, and a retired Unitarian minister who happened to be residing near Florence and who had been called in to officiate. When Cobbe arrived at the English cemetery, Parker’s coffin was lying in the little chapel. Someone had placed laurels on it; Death and Life of Parker 10 she added lilies, a flower she knew Parker loved. Hired pallbearers carried the coffin from the chapel to the grave site. Parker had asked Desor to have someone read the beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount. handed a Bible. So the minister was In a voice catching with emotion, he recited: Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. You awake from your reverie. to leave Parker’s grave. It is 2010 again and time for you You lay your hand on his stone once more and wish him a silent goodbye. Then you walk slowly out of the cemetery, out of the nineteenth century, and into noise and bustle of contemporary Florence. Death and Life of Parker 11 A hundred and fifty years earlier, when the small band of mourners took their own slow walk out of this same cemetery, they also experienced a strange transition. Florence had chosen May 13 to celebrate the Piedmontese constitution, and every building was gaily decorated with red, white, and green flags. A common thought struck Parker’s friends. "It is a festival for us also," they said to one another, "the solemn feast of an Ascension." Sources: Parker’s diary for 1859 is at Meadville Lombard Theological School library; his journal for 1859-1860 is in the Theodore Parker papers at the Andover-Harvard Theological School library; original copies of his letters from his last year are in many archives, notably the Boston Public Library and the State Archives of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, in the Edouard Desor Papers. Desor’s diary can be found at the University of Neuchâtel. John Weiss’s Life and Correspondence of Theodore Parker (1864) contains the first publication of Parker’s autobiography, a text of his Experience as a Minister, and selections from his diary, journal, and letters. It can be found on Google Books, as can Cobbe’s memoir, The Life of Frances Power Cobbe (1904), which contains her accounts of Parker’s death, and editions of all of Parker’s writings. The large, carved, white marble stone found today at Parker’s grave was erected his admirers 1892. It replaced the original stone, small, gray, and unadorned, which they considered too modest.