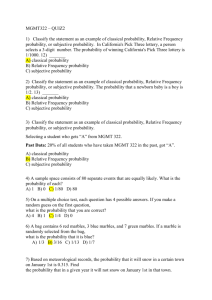

Mind-Body Problem

advertisement