Abstract: Introduction: Late onset group B streptococcal (GBS

advertisement

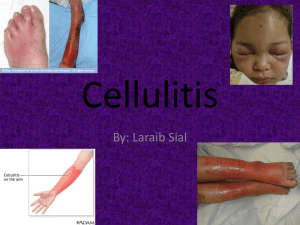

Abstract: Introduction: Late onset group B streptococcal (GBS) infection most commonly manifests as nonfocal meningitis and/or bacteremia, but also causes a spectrum of focal disease including cellulitisadenitis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.[1] Cellulitis frequently occurs in the submandibular and preauricular areas, and less commonly in the submental, retropharyngeal, cervical, and inguinal regions.[2-9] Baker noted the occurrence of underlying adenitis in 15 of 16 cases of cellulitis, but isolated GBS adenitis has been reported.[2, 10] The pathogenesis of cellulitisadenitis syndrome includes mucus membrane colonization with subsequent blood stream invasion and soft tissue seeding.[4, 5] Alternatively, an 80% concurrence of cellulitis with ipsilateral otitis media suggests primary infection with lymphatic spread and secondary bacteremia.[2] Cellulitis-adenitis, while an infrequent manifestation of GBS infection, can be the initial sign of invasive disease, and indicates underlying bacteremia and meningitis in 91% and 24% of cases respectively.[11] Infants with cellulitis-adenitis therefore require blood and cerebrospinal fluid sampling to establish the extent of disease and guide antimicrobial therapy.[11, 12] We present an infant with rapidly progressing submandibular cellulitis-adenitis and GBS septicemia, and a 20-year review of cellulitis-adenitis syndrome at our institution to further characterize this rare, but clinically significant infectious syndrome. Methods: Illustrative case: A 27-day old African-American male infant was admitted with 1-day of irritability and poor feeding followed 2-hours later by fever (38. 3°C) and respiratory distress. The infant was born after 39-weeks of gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a GBS+ woman who received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis >4-hours prior to delivery. No neonatal complications occurred. At admission, the infant was irritable, had a rectal temperature (38.1°C), and noted to have left submandibular erythema, swelling, and tenderness. Ultrasonography excluded a fluid collection in an underlying indurated, nonfluctuant, and tender anterior cervical mass. The peripheral leukocyte count was 3700/mm3 (3.7 × 109 /L) with 29% polymorphonuclear neutrophils and 28% bands. A urinalysis was unremarkable and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 1/mm3 (1 × 106 /L) leukocytes, 3 red blood cells/mm3 (3× 106 /L), 63 mg/dL (0.63 g/L) protein, and 47 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L) glucose. The infant was initially treated with ampicillin (300 mg/kg/day) and gentamicin (4 mg/kg/day). Blood culture was notable for gram positive cocci on staining and subsequently grew type *** GBS; urine and CSF were sterile with no organisms on gram stain. Therapy was changed to intravenous potassium penicillin G (240 000 units/kg/day) on the second hospital day, and treatment was discontinued after a total of 10-days of penicillin therapy. Blood cultures were sterile by hospital day two, and there was resolution of signs of infection by hospital day three. He was discharged with no apparent sequelae. A 27-day old African-American male infant was brought to the emergency department with irritability and poor feeding for 5-hours. The parents initially presented to their primary care physician who noted the infant to be febrile (38. 3°C) with irregular respirations, a clear chest, and 85% oxygen saturation two hours after the onset of symptoms. The infant was placed on supplemental oxygen and transported to the emergency department (ED). The parents denied upper respiratory symptoms. He was born at 39-weeks of gestation by vaginal delivery to a GBS+ woman who received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis >4-hours prior to delivery. No neonatal complications occurred. On admission, the infant was irritable with heart rate 173/minute, respiratory rate 48/minute, blood pressure 83/45 mm Hg, a rectal temperature of 38.1°C, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air by pulse oximeter. Significant findings included left submandibular erythema and swelling with focal anterior cervical induration. The involved area was tender, but not fluctuant. Tympanic membranes were unremarkable, and capillary refill was 4-5 seconds peripherally. The peripheral leukocyte count was 3700/mm3 (3.7 × 109 /L) with 29% polymorphonuclear neutrophils and 28% bands. A urinalysis was unremarkable and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 1/mm3 (1 × 106 /L) leukocytes, 3 red blood cells/mm3 (3× 106 /L), 63 mg/dL (0.63 g/L) protein, and 47 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L) glucose. Ultrasonography noted prominent lymph nodes and no fluid collection. The infant was initially treated with fluid resuscitation, ampicillin (300 mg/kg/day), and gentamicin (4 mg/kg/day). Blood culture was notable for gram positive cocci on staining and subsequently grew type *** GBS; urine and CSF were sterile with no organisms on gram stain. Therapy was changed to intravenous potassium penicillin G (240 000 units/kg/day) on the second hospital day, and treatment was discontinued after a total of 10-days of penicillin therapy. Blood cultures were sterile by hospital day two, and there was resolution of signs of infection by hospital day three. He was discharged with no apparent sequelae. Figure 1. Erythema and swelling in the left submandibular region. Results: Discussion: References: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Howard, J.B. and G.H. McCracken, Jr., The spectrum of group B streptococcal infections in infancy. Am J Dis Child, 1974. 128(6): p. 815-8. Baker, C.J., Group B streptococcal cellulitis-adenitis in infants. Am J Dis Child, 1982. 136(7): p. 631-3. Bourgeois, F.T. and M.W. Shannon, Retropharyngeal cellulitis in a 5-week-old infant. Pediatrics, 2002. 109(3): p. E51. Hauger, S.B., Facial cellulitis: an early indicator of group B streptococcal bacteremia. Pediatrics, 1981. 67(3): p. 376-7. Patamasucon, P., J.D. Siegel, and G.H. McCracken, Jr., Streptococcal submandibular cellulitis in young infants. Pediatrics, 1981. 67(3): p. 378-80. Perez Solis, D., J.J. Diaz Martin, and E. Suarez Menendez, Neonatal retroauricular cellulitis as an indicator of group B streptococcal bacteremia: a case report. J Med Case Rep, 2009. 3: p. 9334. Pickett, K.C. and K.J. Gallaher, Facial submandibular cellulitis associated with lateonset group B streptococcal infection. Adv Neonatal Care, 2004. 4(1): p. 20-5. Rand, T.H., Group B streptococcal cellulitis in infants: a disease modified by prior antibiotic therapy or hospitalization? Pediatrics, 1988. 81(1): p. 63-5. Shetty, S.K. and D. Hindley, Late onset group B streptococcal disease manifests as submandibular cellulitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010. Fluegge, K., et al., Incidence and clinical presentation of invasive neonatal group B streptococcal infections in Germany. Pediatrics, 2006. 117(6): p. e1139-45. Albanyan, E.A. and C.J. Baker, Is lumbar puncture necessary to exclude meningitis in neonates and young infants: lessons from the group B streptococcus cellulitis- adenitis syndrome. Pediatrics, 1998. 102(4 Pt 1): p. 985-6. Mittal, M.K., S.S. Shah, and E.Y. Friedlaender, Group B streptococcal cellulitis in infancy. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2007. 23(5): p. 324-5.