Q Topic 16 notes - The University of West Georgia

advertisement

GEOL 2503 Introduction to Oceanography

Dr. David M. Bush

Department of Geosciences

University of West Georgia

Topic 16: Waves

POWERPOINT SLIDE SHOW NOTES

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Topic 16. Waves

What is a wave? We are talking about waves in water, but in an earlier Topic we talked

about sound waves traveling through water and through Earth. There are many different

types of waves.

It’s easy to visualize the power of the water, of waves, that is battering this ship.

How does energy get into the water?

However it happens, the process is called the generating force.

The opposing force, trying to restore the water surface to its flat state, is called the

restoring force.

The tiny waves are ripples (also called capillary waves), the large waves are gravity waves

There are other ways to classify waves besides the type of generating and restoring

forces. When you go to the beach, the waves you see rolling in can properly be called

wind, gravity, surface, progressive waves. They are generated by the wind, gravity is the

restoring force, they move on the surface of the water, and the progress, or move

forward. These are the most common types of waves, though there are others. Wind

waves are created by friction. Not really different from the trade winds creating ocean

currents, except wave generation is at a much smaller scale. Friction transfers energy

from the wind into the water surface.

A very important thing about waves is that even though energy is being transported, the

medium is not transported. Just like air is the medium that transport the energy of my

voice, the air is not transported. Same thing with wave energy. The water does not move

forward, only the energy.

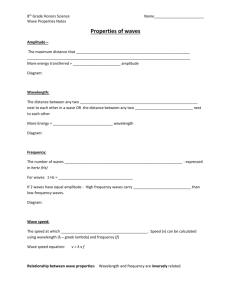

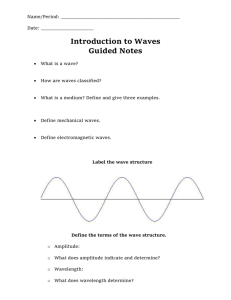

Wave terminology

Wave terminology illustrated

As a wave moves, the water moves in circles but there is no net forward motion. The

circles are called wave orbits.

Orbital wave motion illustrated. Watch a cork or seagull or small boat as waves pass

under them. The move in circular motion ending up where they started.

Water particles make one complete orbit in one wavelength. All the water is rotating, but

only a few orbits are highlighted. There is a loss of with depth because of transferring

energy through the water column. Thus, wave orbitals decrease in diameter. At a depth

of one-half a wavelength, there is essentially no orbital motion. For example, imagine a

wave with a wavelength of 100 meters. One-half of 100 = 50. So the wave orbitals extend

down to about 50 meters.

Speed is a measurement of length divided by time. Miles per hour, for example. Wave

speed is wavelength (usually measured in meters) divided by the wave period (usually

measured in seconds). The term “celerity” is used to define wave speed.

There is something very interesting about progressive waves. Depending on the water

depth and wavelength, their behavior can be quite different. A wave traveling in water

depth equal to or greater than 1/2 wavelength is called deep-water wave. A wave

traveling in water depth equal to or less than 1/20 wavelength is called shallow-water

wave. Let’s take our 100-meter wavelength wave. If it is travelling in water depths of 50

meters or greater, it is a deep-water wave. If it is travelling in water depths of 5 meters or

less, it is a shallow-water wave. What’s the big deal? It’s all a matter of whether or not

the wave orbitals interact with the sea bottom.

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

Note the difference in the orbitals between deep- and shallow-water waves. We’ve

already seen deep-water waves. Circular orbitals decrease in diameter in depth until their

diameter is zero at a water depth of L/2. The wave orbitals in shallow water interact with

the sea bottom so much that they are deformed into ellipses. The ellipses have a

constant width axis with depth, but the height axis decreases with depth until at the

seafloor the water is not orbiting so much as simply swashing back and forth. Perhaps

you’ve noticed this at the beach in very shallow water.

And the big deal about all this is the difference in behavior between deep- and shallowwater waves.

Deep-water waves progress at a speed controlled by their wavelength. The longer the

wavelength, the faster they move. This leads to a process called wave dispersion.

Deep-water waves move away from their area of generation.

Another use of the word “sea.” Waves in the area of generation.

Wave dispersion is a sorting out of waves by wavelength as they progress from the area of

generation. Long wavelength waves moving faster than shorter wavelength waves.

Wave dispersion. A sea surface in the area of generation and with very irregular wave

heights, lengths, and periods, eventually is sorted out by wave dispersion into a very

regular sea surface. These sorted-out waves are called swell. The area of ocean surface

over which the wind is blowing (a storm or trade winds, for example) is called the fetch.

Sea

Swell. Swell is what we usually experience when we go to the beach. Nice regular waves

with more or less constant wave lengths and wave periods.

A ship in a storm.

Swell

Waves don’t occur by themselves. The wind creates many waves, called wave trains. The

lead waves lose energy as they deform the sea surface ahead of them. Thus, the leading

waves are lost and new waves are catching up with the group to take its place.

The speed of an individual wave is greater than the speed of the wave train.

Group speed is the speed of the wave train and is equal to 1/2 of the wave speed

(celerity).

Wave height is a representation of how much energy the wind can transfer to the water

surface. The energy transfer depends on three factors: wind speed, wind duration, and

fetch.

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

Wind blows across the water surface, transferring as much energy as possible based on

the three controlling factors. When the largest possible waves for that set of conditions

are created, the situation is called a fully developed sea. Check out this site where you

can vary the factors and see the resulting waves{

http://www-tc.pbs.org/wnet/savageseas/multimedia/wavemachine.swf

For a wind speed of 58 mph, notice the increase in wave heights wavelength, period, and

speed with increasing fetch.

Wave terminology. Significant wave height is used more frequently than maximum or

average wave height to describe local wave conditions, especially for marine engineering.

It’s a better representation of the energy of the system during storms than a maximum

wave’s height which may be large but also rare.

Some conditions for a fully developed sea

Waves can be generated by more than one storm at the same time. As they move, the

waves may interact.

When waves interact, if crests and troughs match up, constructive interference occurs

and there is an addition of energy resulting in larger waves. When two waves are offset

by about one-half a wavelength, the crests and troughs cancel out each other through

destructive interference and smaller waves result.

Episodic or rogue waves can be caused by constructive interference. Accounts of large

waves “coming out of nowhere” are numerous, and may account for many lost ships.

Rogue waves

Wave steepness

Steepness of a newly-formed wind wave

Now to shallow-water waves. The intense interaction of wave orbitals with the sea

bottom makes shallow-water wave behavior quite different from that of deep-water

waves. The speed of a shallow-water wave is controlled by water depth. The shallower

the water, the slower the wave. This leads to the processes of wave refraction and wave

breaking.

Watch the Waves, Beaches and coasts video in the “Earth Revealed” series on learner.org.

Wave refraction

Wave crests bend as waves move into shallow water.

On irregular coasts, wave refraction results in a concentration of wave energy on

headlands, speeding their erosion.

Waves refract, or bend, around this rocky point

Wave refraction around a rocky island

Wave refraction into a small bay

Wave refraction into a small coastal bay

Wave breaking. We’ve come from sea, to swell, and now to surf. The end of wave, the

final dissipation of energy on the shore. A big change occurs in the surf zone. Surf zone

waves do transport water forward.

Deep-water waves transitioning to surf. In shallow water the back of a wave is moving

faster than the front, causing water to pile up and eventually fall forward as a breaking

wave. Water moving up above sea level due to the forward momentum of the wave is

called the swash zone. Gravity pulls the water back down to sea level. The surf zone is

where waves transition to water moving forward. That is why we can surf on breaking

waves, but not on deep-water waves.

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

Notice how the wave orbitals are deformed forward in shallow water. Recall that once a

wave is formed, the wave period remains constant, and that a wave orbital completes one

revolution in one wave period. So orbital speed (controlled by wave period) is constant,

but celerity decreases as water depth decreases. At some point, orbital velocity becomes

greater than wave speed and the water of the wave crest is thrown out ahead of the

wave, causing the wave to break.

A breaking wave, often called a breaker, throws water up above sea level. That is called

wave swash. Water pulled back down into the ocean by gravity is called backwash.

The type of breaking wave depends on the steepness of the seafloor.

Longshore current

Wave swash carries sand up the beach, and backwash carries it back down. The zigzag

motion is caused because waves usually approach the beach at an angle, and the sand is

pushed up the beach at that angle. But gravity pulls the backwash water and sand

straight back down the beach. The sand thus moved is called beach drift. The longshore

current also moves sand parallel to the beach. The movement of sediment along the

shore by longshore current and beach drift is called longshore transport.

Breaking waves push water against the shore. One result is driving the longshore current.

Another is creating rip currents. Water pushed above sea level by breaking waves can

sometimes return to the sea in narrow flows called rip currents.

Rip currents are dangerous, but they are small and can be avoided with a little knowledge.

Rip currents may be only 10 meters or so wide, and 100 meters long, depending on the

size of incoming waves.

Rip currents are visible here as narrow zones of no breaking waves.

Swimmers can get caught in rip currents and carried out to sea. Frequently the swimmers

will panic and try to swim back to shore against the current. Panic or fatigue can have

deadly consequences.

Fortunately, there is a very simple way to get out of a rip current. Simply swim parallel to

shore beyond the rip current. Then you can safely swim back to shore. Often, swimmers

do not know this technique, or are too panicked to remember it.

Tsunamis are surface, gravity, progressive waves, but are not generated by the wind. The

generating force is some type of seismic event, usually an undersea earthquake.

Generation of tsunamis.

Tsunami characteristics.

Example of a tsunami caused by a fault.

The 2004 Indonesian tsunami killed over 250,000 people. It was caused by a massive

undersea earthquake.

Indonesian tsunami, December 26, 2004. Check out NOAA’s Center for Tsunami Research

page for all kinds of neat information: http://nctr.pmel.noaa.gov/index.html. An

animation of the 2004 Indonesian tsunami can be found here:

http://nctr.pmel.noaa.gov/Mov/TITOV-INDO2004.mov

Let’s look at wave speed for a tsunami. Recall that the formula for wave speed is

wavelength divided by period, or L/T. Tsunamis can have wavelengths of hundreds of

kilometers and wave periods of tens of minutes. Let’s use L = 200 km and T = 10 minutes.

200 km ÷ 10 minutes = 20 km/min or 1200 km/hour which is equal to 745 mph. Tsunamis

move faster than the planes flying overhead!

The city of Banda Aceh was one of the hardest hit by the 2004 tsunami.

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

Banda Aceh Shore, Indonesia: after

Gleebruk Village (1): before

Gleebruk Village (1): after

Internal waves

Internal waves diagram

Standing waves

Standing waves diagram. At nodes, the water level doesn’t change. At antinodes the

water level is maximum at the crest of a standing wave, and minimum at the trough. This

animation gives you an idea of what might happen when an incoming wave is reflected off

a seawall or rocky coast:

http://faraday.physics.utoronto.ca/IYearLab/Intros/StandingWaves/Flash/standwave.swf

A seiche (pronounced “saysh” or “seesh”) is a special kind of standing wave occurring

within an enclosed basin. The initial displacement could be caused by a chunk of a glacier

falling into a lake, wind pushing water to one side of a lake, or an earthquake. Jump into a

small swimming pool and you can create your own seiche. Check out this site:

http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/earthguide/diagrams/waves/swf/wave_seiche.html

The spectrum of wave types. Wind waves are so common, that collectively they contain

more energy than any other type of waves. Most wind waves have periods of 1-30

seconds. We’ll talk about tides next.