Experiment with Chocolate Crystal Formation in the Kitchen

advertisement

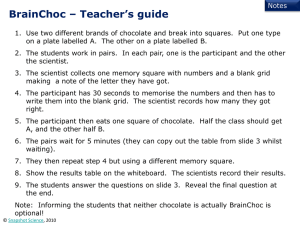

Experiment with Chocolate Crystal Formation in the Kitchen Target Grades: 5-8 Content Areas: Physical Science, Chemistry Activity Type: Food experiment Time required: About 1 hour NGSS: MS-PS1-4: CCSS. ELA-Literacy.RST.6-8.3, ELA-Literacy.RST.6-8.9 What do you think of when you think of crystals? Do emeralds, quartz, snowflakes, or maybe rock candy come to mind? You may be surprised to learn that chocolate, that delightful confection, is a crystal too. Crystals are solids whose molecules, atoms, or ions are connected to one another in an organized pattern—called a crystalline structure—that repeats over and over throughout the solid. Chocolate molecules are often arranged in this way, which is why a chocolate bar gives a satisfying “snap” when you bite into it. When chocolate is heated, thermal energy shakes apart its ordered crystalline structure, causing it to melt into a liquid. Because chocolate can contain different types of crystals that melt at unique temperatures, a careful melting process called “tempering” is used to melt all but the most desirable crystal type, known as betacrystals. As the liquid chocolate cools, it recrystallizes using the few remaining betacrystals as a template. The resulting structure is almost entirely made up of betacrystals, which are what make chocolate bars hard and shiny. Chocolatiers will sometimes add pre-tempered chocolate bits to cooling liquid chocolate to help guide beta-crystal formation in a method called “seeding.” Extreme temperature changes and the presence of other contaminants can interfere with the recrystallization process by preventing the chocolate crystals from organizing properly into a stable crystalline structure, resulting in mushy chocolate. Watch the Science Friday video “Choc Full of Science” to learn about how chocolate is made and tempered to produce the perfect chocolate crystals. http://sciencefriday.com/video/05/08/2014/choc-full-of-science.html In the following experiment, you will become an experimental chocolatier and determine how different melting and cooling procedures impact the shine, hardness, and texture of finished chocolate. The process is a bit messy, but even the most unsightly products will still taste delicious! Materials: - 4 - 6 small microwave-safe glass bowls or coffee mugs, cleaned and thoroughly dried - 4 large bars of semi-sweet or dark chocolate—about 60-70% cacao is recommended (no nuts or other add-ins). Set aside a couple of squares, then chop the remaining chocolate into little bits and separate them evenly among the bowls - A microwave OR a pot of water just smaller than the glass bowls so that one bowl can be set inside the pot without touching the bottom - 4 clean and dry spoons or spatulas (non-wooden) - Cookie sheet lined with parchment paper or wax paper - Thermometer (optional, but helpful) - Glass of water - Pencil and ruler Safety Considerations: Make sure an adult cuts up the chocolate using a sharp knife and cutting board. The bowls and the melted chocolate inside them might get pretty hot, so experimenters should use hot pads and wear aprons when handling heated bowls of melted chocolate. Restrict this experiment to the kitchen or laboratory to avoid chocolate stains on any fabrics or carpeting. Melting & Sampling Procedure 1. Use your pencil and ruler to draw a 2x3-inch grid of three-inch squares on the paper lining your cookie sheet. This is where you will deposit chocolate samples to cool for observation. 2. Microwave method - Place one of the bowls of chocolate in the microwave and microwave on half-power in 30-second bursts, stirring each time, until the chocolate is mostly melted. Remove the bowl from the microwave and stir with the spatula until all the little clumps are gone. The liquid chocolate should be warm, verging on hot to the touch (about 110o F if using a thermometer). Double-boiler method - If you are using a double-boiler, melt the chocolate over simmering (not boiling water), stirring constantly with a clean spatula until the chocolate is mostly melted. Remove from heat and stir with the spatula until all the little clumps are gone. The liquid chocolate should be warm, verging on hot to the touch (about 110o F if using a thermometer). 3. Using the tip of your spatula, scoop out and dribble a small amount of chocolate into one of the squares that you drew on the parchment/wax paper, and use your pencil to label the square with the preparation method. The Experiment The following modifications to the melting procedure described above will help or harm the chocolate recrystallization process. Try to predict how temperature changes, contaminants, and seed crystals will affect chocolate crystallization and the resulting chocolate. You can record your predictions on the chocolate crystal prediction sheet. Use one of the bowls of crushed chocolate for each of the following modifications (for some, you may be able to reuse the chocolate). After each experiment, label the sample on the parchment paper with a brief description of how it was prepared. Seeding – After step #2, let the chocolate cool slightly (to about 89o F), and add a chunk of solid chocolate from your original bar directly into the melted chocolate. Mix well to cool the chocolate. The chunk acts as a “seed” crystal to provide a scaffold for new crystals to grow on and does not need to melt completely, remove any leftover chunks before putting a sample onto the cookie sheet. Scorching – In step #2, continue heating the chocolate beyond the point where it has just melted, until it begins to steam or bubble slightly. This will not only melt all crystals in the chocolate, but will also begin to break down other molecules in the chocolate as well, causing them to separate and, in some cases, evaporate from the molten chocolate. Seizing - After step #2, sprinkle some droplets of cold water into the melted chocolate, and keep stirring as it cools. Some of the molecules in chocolate are water-soluble and will dissolve into the added water, while others are hydrophobic (repelled by water) and will clump together. Shocking – After step #2, rest the bottom of one of the bowls in ice water while stirring the chocolate continuously until it becomes difficult to stir, then continue with step #3. Marble tempering - After step #2, pour the liquid chocolate out onto a marble slab. Using a clean spatula or metal scraping tool, smooth the chocolate out to help it cool, and then “work” it continuously around the slab with the spatula until it becomes thick and viscous. DIY method: Think creatively about another way that you could treat the chocolate before it cools. What could you add to this recipe or do differently that might change the shine, hardness, and texture of the chocolate? If you try your own method, be sure to place a sample on the cookie sheet and label it with a description of the method you used. Make Chocolate Observations Once your various samples have finished cooling to room temperature on the cookie sheet, record some observations about the chocolate’s shine, hardness, and texture on the chocolate observation sheet. Which method gave the chocolate a shiny surface without streaks or clumps? Pick up the chocolate and try to break it between your fingers. Does it snap, bend, or get mushy? Lastly, take a bite out of the chocolate and describe its texture as it melts in your mouth. Is it lumpy, creamy, or waxy? Based on your observations, which method would you recommend to someone trying to coat a strawberry in a hard chocolate shell? Use your experimental observations to determine which method resulted in the most complete betacrystals. Standards MS-PS1-4: Develop a model that predicts and describes changes in particle motion, temperature, and state of a pure substance when thermal energy is added or removed. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RST.6-8.3: Follow precisely a multistep procedure when carrying out experiments, taking measurements, or performing technical tasks. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RST.6-8.9: Compare and contrast the information gained from experiments, simulations, video, or multimedia sources with that gained from reading a text on the same topic. Chocolate Observation Sheet While your chocolate samples are cooling to room temperature, list the different modifications you made to the basic melting and sampling procedure. Use the table below to record each of the following chocolate characteristics. - Shine - Is the surface shiny and smooth, lumpy, streaky, or cloudy? - Hardness - Pick up the chocolate and try to break it between your fingers. Does it snap, bend, or get mushy? - Texture - Take a bite out of the chocolate and describe its texture as it melts in your mouth. Is it lumpy, creamy, or waxy? Chocolate Preparation Modification Surface shine Hardness Texture Based on your observations, which modification would you recommend to someone trying to coat a strawberry in a hard chocolate shell? Which method would you use to form the soft center of a truffle? Why? Based on your observations, which modification produced the most stable crystal structure? How can you tell? Which modifications do you think disturbed or prevented the re-formation of crystals in the chocolate as it cooled? What observations did you make that suggest that re-crystallization was prevented? Chocolate Prediction Sheet: How will the way you prepare the chocolate affect beta-crystal formation? Chocolate Preparation Modification Seeding –The chunk of tempered chocolate acts as a “seed” crystal to provide a scaffold for new crystals to grow on. Scorching – Chocolate is heated until all crystals are melted and the molecules within chocolate begin to break down, causing them to separate and, in some cases, evaporate from the molten chocolate. Seizing - Droplets of cold water are sprinkled into the melted chocolate. Keep stirring as it cools. Some of the molecules in the chocolate are watersoluble and will dissolve into the added water, while others are hydrophobic (repelled by water) and will clump together. Shocking –The bottom of the bowl is placed in ice water while the chocolate is stirred continuously until it becomes difficult to stir. Marble tempering - The liquid chocolate is poured out onto a marble slab to help it cool, then scraped across the surface continuously until it becomes thick and viscous. DIY method: Describe how you plan to modify the standard melting procedure: Model Do you expect this modification to help or harm beta-crystal formation? Why?