Mahina Kaholokula

advertisement

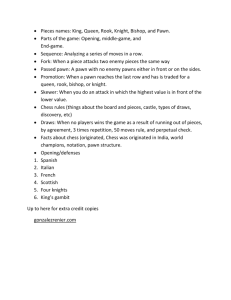

Mahina Kaholokula Math 7: Mathematical Puzzles 23 May 2013 The Art of Chess Puzzles Chess is one of few things that has stood the test of time. Originating as far back as the 6th century, it has developed over time to become the worldwide sport that you see today. There are clubs and competitions formed around chess; there are books and movies dedicated to its history and its strategies; and there are hundreds of different variations of the game now propagating around the world, from using non-standard boards (ex. in dimension), to non-standard pieces (fairy chess, for instance, may use a piece called the “nightrider” 1 which may move any length in the straight direction given by a standard knight move – i.e. 1 cell up, 2 cells to the side), or with non-standard rules (“suicide chess” has the surprising objective of wanting to lose your king first in the game). One twist to chess is to create puzzles and problems involving the general game rules for others to then solve. The scope and variety of the puzzles is enormous: some start out with a pre-configured chessboard and task the puzzler with having one side checkmate the other within a certain number of moves. Others start with the endgame and have the puzzler work backwards to figure out what the last move played might have been. There are “tour” puzzles that focus on the movement of pieces and on paths that could (and could not) be taken. While others still are “domination” problems, 1 “Fairy Chess Piece.” interested in the attack range of the pieces and how to set up specific pieces to attack specific squares. The list is extensive, with a range of themes and difficulty levels, but they all share a couple of key qualities, including the fact that they all embody a certain elegance, and they are all enjoyable to both create and especially solve. The most common chess problems by far are those in which the board is set up in a pre-determined configuration and it is the duty of the puzzler to complete some task, often a checkmate for one side or the other, in a given number of moves. This type of puzzle tends to advantage those who actually play a bit of chess, as they will have more experience with seeing connections and interactions between the pieces. (In fact, chess players often use this type of puzzle to practice and further develop these skills of perspective and observation.) Still, chess puzzles are meant to be accessible to everyone, no matter the skill level, and the only information the puzzler really needs in order to solve these problems is knowledge of how the pieces move. Thus we come to the classic chess puzzle, consisting of the chessboard, a configuration of pieces, and the sentence “Mate in Y moves. X to move” (X representing a color and Y a number). For example, here is one: Figure 1. Mate in 2 moves. White to move. Now, if we are to believe that the puzzle is indeed possible, then one conclusion you must come to is that there is a unique set of moves that will get White to mate in 2 moves. This means that once White moves, Black should not have any choice of which piece to move where because this is the only way to ensure that White will win every time no matter how Black tries to stop it. Thus we are looking for a move that forces Black’s next move. Often this means putting the king in check in a way that only allows one option for Black getting out of check. This will then lead to White’s winning move to checkmate. Here, there are three options for how White can check the Black king: move queen to g5, move bishop from c4 to f7, or move queen to f7. Let’s consider these choices. We can reject the first, since a trade of queens will likely ensue, and White won’t shake Black’s defense at all. The second seems plausible, but we lose what is called a “pin” in chess, where right now the bishop at c4 is poised to check the Black king as soon as the space in f7 is clear. This means that Black has no other option but to keep that space occupied. If we move bishop to f7 and the bishop is taken by Black’s rook, then White loses the pressure that this pin strategy is useful for. Thus, we come to option 3, moving the White queen to f7. It seems counterintuitive to move the queen to such a vulnerable spot, but, in fact, sacrifice is often necessary in chess and can have a winning payoff in the end. By moving queen to f7, we force Black’s next move: rook takes queen (Black can do nothing else to get out of check since the King is not able to move into any square out of check). The winning move here for White is then clear: when the Black rook takes the White queen at f7, the rook is not only pinned in this space by the White bishop, but a new vulnerability to the Black king has opened up via the square f8. White can now take advantage of this and move his rook to e8, thus checkmating the Black king. This was more of a dense example to use with some formal tactics involved, but it illustrates well the strategy and excitement of the game. The strategy obviously comes from looking ahead in the game, finding that first move to force the opposition into a vulnerable position, and then taking advantage of that vulnerability. The excitement is closely related, watching as the drama of finding the right moves and exploiting vulnerabilities unfold in exactly the right fashion. Furthermore, by doing these puzzles more and more, you learn different strategies and plays, start noticing different connections between pieces and placements, and all the while enjoying the challenge that the puzzle sets out for you. Figure 2: Examples of Knight's Tours. The lines represent each “jump” the knight makes. One very popular chess puzzle, which has been around for over 1000 years, is the Knight’s Tour2. The object of the game is to find a path around a chessboard that allows a knight to move to each square on the board exactly once. A common variation on the puzzle is to distinguish a “closed” path from an “open” one (a closed path ends on the same square it started on where an open one doesn’t have this restriction). Over the years, many chess masters, mathematicians, computer scientists, and other curious puzzlers have dedicated time and effort to solving this problem, and it was quickly observed that there was no one unique solution to find. In fact, a fellow named Brendan McKay created a computer program to calculate the total number of Knight’s Tours possible on the standard 8 x 8 chessboard and the result was an astounding 13,267,364,410,5323! Mapping out these journeys for the purpose of a puzzle, however, requires a little more personal investment in the game. Although there are multiple methods that have been proven successful, one of the simpler ones is de Moivre’s technique, named after the man who discovered it in the early 18th century. His idea was this: start in the outer ring of the board (the outer 2 loops since a knight must always move in an “L” shape) and stay as close as possible to this outer ring before working your way in to cover the center squares4. 2 Jelliss, George McKay, Brendan D. 4 Watkins, John J. 3 Figure 2: De Moivre’s technique. By starting on square 1 and moving around the outer ring of the board, only moving into the inner rings briefly when necessary, the tour can end on square 64. Interestingly, square 64 can also connect back to square 1, creating a closed path solution. Figure 3: Number of Possible Moves. This graph shows the number of possible moves a knight can make from a given square. Clearly there are more options amongst the inner squares. This strategy, easy to remember and implement, is always a good place to start when trying to find a Knight’s Tour around a new board. Although I did not delve into the details behind the technique, part of its success must be based on the fact that by touring the outer ring first, you are touching on those squares with the fewest options for further movement first, which allows for more flexibility among the inner rings later on in the game. By this I simply refer to the fact that a knight can only move to a certain number of squares from any given square, and this number is obviously smaller on the edges of a board, since a knight cannot move outside the board. A very important outcome of this puzzle has been its connection to the mathematical field of graph theory. The idea is to represent the Knight’s Tour as a graph, so that the vertices of the graph represent the squares of the board and the edges connect the vertices that a knight could legally move between. For example, Figure 2 above is a Knight’s Graph representing an 8 x 8 board. This representation becomes analogous to a Hamiltonian path, which is simply a path that touches every vertex in a graph exactly once. (A Hamiltonian cycle is similarly paired with a closed Knight’s Tour.) These representations in graph theory led to the ability of mathematicians to determine whether our not a Knight’s Tour was even possible on a chessboard of any given dimension. The bottom line is that if a Hamiltonian path exists, than a Knight’s Tour is possible, and if a Hamiltonian path does not exist, than there is no legal Knight’s Tour possible on the board5. Figure 4: A Knight’s Graph representing a 4x4 chessboard. There is no Hamiltonian path that exists here, so it is impossible to do a Knight’s Tour on a 4x4 chessboard. This connection between the Knight’s Tour and graph theory led in 1991 to Schwenk’s Theorem, created by Allen Schwenk, which lists out on what chessboards (by dimension) a Knight’s Tour exists. While I will not probe deeper into the proofs of these conditions, I think it’s interesting enough to note them down here: Schwenk’s Theorem: An m x n chessboard with m ≤ n has a Knight’s Tour unless one or more of the following three conditions hold: (a) m and n are both odd; (b) m = 1, 2, or 4; or 5 Watkins, John J. (c) m = 3 and n = 4, 6, or 8.6 While the problem of the Knight’s Tour has been around since the 9 th century, it has taken on a new vitality in the past couple centuries. Famous minds from Euler to Babbage7 have toyed with the puzzle; new solutions and strategies have been brought into existence; and of course there are numerous variations on the puzzle including straying from the standard 8x8 board or using other pieces instead of the knight (with various restrictions here as well). The drama and excitement of finding that perfect journey around a chessboard has thus captured and held the attention and curiosity of minds all around, and continues to do so even to this day. Chess has always been considered a pastime of intellectuals. Starting out as a sport for nobles, chess retained its reputation through the 19th century as a game purely for educated and cultured society before attitudes changed and chess became more widely played across the social ladder8. These stereotypes did not evolve completely without reason, however, as playing chess does take a great deal of skill that only the noble class of earlier centuries had the time to develop. Today, many more people have the time to dedicate to learning such skills, and, indeed, studies have been held that prove that this is time well spent. A good question raised here is what skills, specifically, are being developed by this game? It turns out that there may be more than you might imagine. For instance, there are the more obvious qualities that chess promotes, such as focus 6 Watkins, John J. Jelliss 8 “The History of Chess” 7 and patience in choosing a next move. This choice of which piece to move to what spot also causes the player to think ahead, to anticipate how that move will affect future play, etc. These skills are crucial not only to chess but to life in general, where concentration, patience, looking forward, and strategizing can all help advance your status and quality of life. However, studies have shown that there are other benefits to playing chess, although the correlation between these may not always be as obvious. One study by Stuart Margulies involving 9 mid-elementary schools showed that chess improves reading skills9. A study in China in the late 1970s concluded that chess improves math and science skills as well, and another study in Canada involving 500 fifth graders in the 1980s corroborated this finding. Various other studies and surveys have shown increases in creativity, memory, and self-esteem due to chess as well.10 While these studies may have been based off playing legitimate games of chess, there is no reason to believe that the same won’t hold true for puzzle variations of the game. Intuitively, it certainly seems that many of the same qualities that develop in a good chess player – such as focus, patience, creativity, and anticipation of future consequences – will also develop in a good chess puzzler. Beyond the perhaps more tangible benefits mentioned above, chess puzzles should be valued in their own right. Often preceded by the words “the art of,” chess is a beautiful game. The elegance of a good puzzle is something to be appreciated, and chess puzzles posses this quality. They manifest elegance in simplicity, in directness. There is no trick, no attempt to fool or lead anyone astray with distractions or red 9 Byrne, Beverly Ferguson, Robert C. 10 herrings; the puzzle is straightforward and success is based purely upon will and focus and determination. The emphasis on strategy and economy (how each piece has a completely unique and necessary function without which the puzzle is impossible) only adds to the elegance of the solution. Furthermore, because chess puzzles are purely intellectual, (and not based upon unraveling complex and abstract word problems for instance,) the feeling of accomplishment you feel when you finally find the solution is magnificent. Thus, whether you look at it from an academic viewpoint, a practical viewpoint, or a personal one, the result is that, in the end, chess puzzles are simply worth all the time and effort they require. Works Cited Byrne, Beverly. "Scientific Proof: Chess Improves Reading Scores." Chess Coach Newsletter 6 (Spring 1993): Mephisto and Fidelity. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://chesspuzzles.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/12/study.pdf>. “Fairy Chess Piece.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia Foundation, Inc. 29 April 2013. Web. 22 May 2013. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_chess_piece> Ferguson, Robert C. "Benefits of Chess." Benefits of Chess. Web. 14 May 2013. <http://www.quadcitychess.com/benefits_of_chess.html>. Godden, Kurt. "A Tour of the Knight's Tour." Chess.com. 3 Mar. 2008. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.chess.com/blog/kurtgodden/a-tour-of-the-knightstour?_domain=old_blog_host>. "The History of Chess." ThinkQuest. Oracle Foundation, 22 Sept. 2010. Web. 14 May 2013. <http://library.thinkquest.org/26408/feature/chess_history.shtml>. Jelliss, George. "Introducing Knight's Tours." Introducing Knight's Tours. 2004. Web. 15 May 2013. <http://www.mayhematics.com/t/1n.htm>. McKay, Brendan D. “Knight’s Tours of an 8 x 8 Chessboard.” Australian National University. 1997. PDF file. Watkins, John J. Across the Board: The Mathematics of Chessboard Problems. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2004. Print. Image Bibliography Figure 1: Bain, John. "Chess Puzzles!" ChessPuzzles.com. Web. 22 May 2013. <http://chesspuzzles.com/>. Figure 2: Weisstein, Eric W. "Knight Graph." MathWorld. Wolfram. Web. 21 May 2013. <http://mathworld.wolfram.com/KnightGraph.html>. Figure 3: Keen, Mark R. "The Knight's Tour." Mathematics Dissertation 'The Knight's Tour'. 2000. Web. 21 May 2013. <http://www.markkeen.com/knight/>. Figure 4: “Knight’s Graph.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia Foundation, Inc. 22 March 2013. Web. 21 May 2013. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Knight%27s_graph_showing_number_ of_possible_moves.svg> Figure 5: "Puzzling Graphs: Problem Modeling with Graphs." Good Math Bad Math. Scientopia, 10 Sept. 2007. Web. 21 May 2013. <http://scientopia.org/blogs/goodmath/2007/09/10/puzzling-graphsproblem-modeling-with-graphs/>.