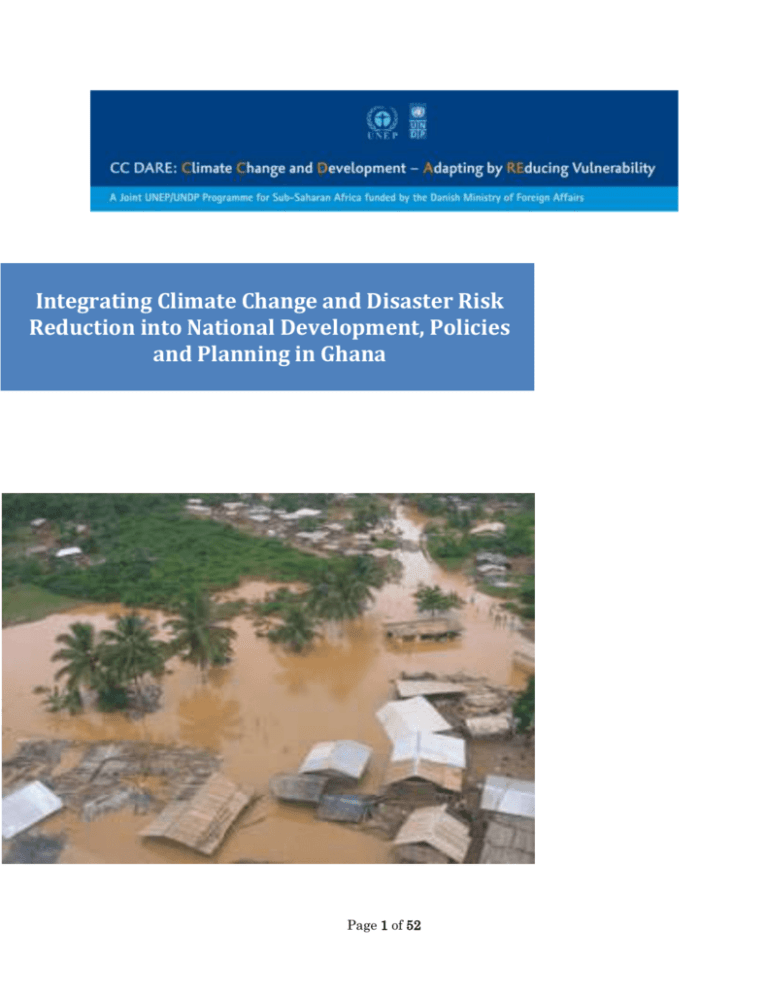

Integrating Climate Change and Disaster Risk into

advertisement