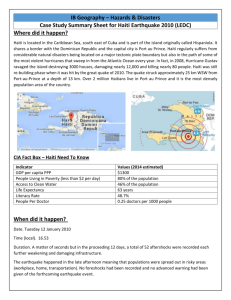

Partners in Health - Carney Global Ventures, LLC

advertisement