EDGAR ALLAN POE

advertisement

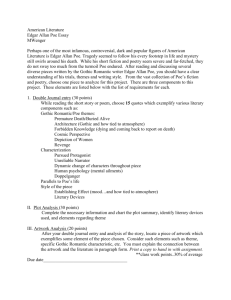

EDGAR ALLAN POE: BIOGRAPHY "Edgar Allan Poe is dead," read the obituary. "This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it. The poet was known, personally or by reputation, in all this country; he had readers in England, and in several of the states of Continental Europe; but he had few or no friends; and the regrets for his death will be suggested principally by the consideration that in him literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars."2 That incredibly nasty appraisal ran six days after Poe was found, disheveled and unconscious, in the gutter of a Baltimore street. Poe lived, barely, for four more delirious days before dying of causes still unknown. The obituary was written by his greatest literary rival, a man named Rufus Wilmot Griswold. Griswold, not content with his handiwork in the obituary, also published a libelous Poe biography full of lies shortly after the poet's untimely death. Add all that to the tall tales that Poe told about himself during his lifetime, and you might begin to understand how Edgar Allan Poe has become, in death, one of the best-loved but least understood writers in American literature. Poe was a master of the short story and narrative poem. He had a gift for suspense and delightfully twisted plots. But his real gift was his ability to understand that part of our psyche that craves the macabre. He could see into the darkest corners of the human mind. As a man who lived and died in poverty—and as a man whose loved ones perished one by one of consumption (a.k.a. tuberculosis)—it's possible that Poe knew those dark places so well because he had so often been there himself. Not that Poe was all serious. He described his stories as "half banter, half satire." 3 He wrote spooky stories in part because he knew they would sell. He sometimes veered into sensationalism for the sake of being sensational, and did so with a winking acknowledgement to readers that he was writing schmaltz on purpose. Though he professed to be in the writing business just for the money, Poe nonetheless changed American literature forever. You don't need to look much farther than today's bestseller lists to see that America still loves a good suspense story. According to Stephen King, who knows a thing or two about telling a scary story, he and his colleagues are all "the children of Poe."4 EDGAR ALLAN POE: CHILDHOOD Edgar Poe (the Allan came later) was born 19 January 1809 in Boston to Elizabeth Arnold Poe and David Poe, Jr. His parents were traveling actors. The family was dirt poor. By 1811, his father had abandoned the family, leaving Elizabeth Poe alone with two-year-old Edgar, his elder brother Henry, and his infant sister Rosalie. And things soon got worse. On 8 December 1811, Elizabeth Poe died of tuberculosis in Richmond, Virginia. News soon arrived that David Poe had also died of the same disease, within days of his estranged wife. The three Poe children were split up. Henry went off to live with his paternal grandparents. Rosalie was adopted by the Elizabeth Poe, Poe’s mother Mackenzie family of Richmond. And Edgar was taken in by the family of John and Frances Allan, a well-to-do Richmond couple unable to have children of their own. He added his foster family's name to his own, becoming Edgar Allan Poe. John Allan was a successful merchant, and Edgar grew up fairly comfortably. He was close to his foster mother, Frances, but never with his foster father, who always thought Edgar was a punk, shamefully ungrateful for all the couple did for him. From 1815 to 1820, the family lived in England, where young Edgar got a good education at a school outside of London. In 1824, when he was John Allan, Poe’s foster father fifteen and back in Richmond, Poe penned his first poem: "Last night, with many cares & toils oppres'd,/ Weary, I laid me on a couch to rest."5 Poe enrolled at the University of Virginia in 1826, less than a year after the school founded by Thomas Jefferson first opened its doors to students. John Allan had sent Poe to college without enough money to get by. To make ends meet, Poe started gambling. By the end of his first semester he had run up a $2,000 debt, which John Allan refused to pay. Poe resorted to burning his dorm room furniture to keep warm that winter. Humiliated, he left the University of Virginia. Frances Allan, Poe’s foster mother EDGAR ALLAN POE: WEST POINT In 1827, Poe enlisted in the U.S. Army under the name "Edgar A. Perry." He did well as a soldier, rising to the rank of sergeant major. He also continued to write. A book of his poetry was published anonymously (the author being listed only as "A Bostonian"). In April 1829, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. A few months later, he published his second book of poetry, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems. Poe soon realized that West Point wasn't for him. He decided to get himself kicked out of school, which he successfully accomplished by refusing to attend chapel or classes. He was court-martialed and dismissed. "The army does not suit a poor man — so I left W. Point abruptly," he later wrote, "and threw myself upon literature as a resource. I became first known to the literary world thus."7 Poe published several anonymous short stories plus another book of poems. Almost immediately after he left West Point, his brother Henry died of tuberculosis. Poe began (and finished) his career as a starving writer. Though John Allan had remarried a wealthy woman, he refused to support his foster son, who was constantly asking for money. "It has now been more than two years since you have assisted me, and more than three since you have spoken to me," Poe wrote in his final letter to his foster father in 1833. "If you will only consider in what a situation I am placed you will surely pity me — without friends, without any means, consequently of obtaining employment, I am perishing — absolutely perishing for want of aid. . . . For God's sake pity me, and save me from destruction."8 John Allan did not respond. And when he died on 27 March 1834, Allan omitted his adopted son from his will entirely. An artist’s rendition of Poe at West Point EDGAR ALLAN POE: WRITER In December 1835, Poe was hired as the editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, staving off starvation. Then, in one of the strangest twists in his biography, he fell in love with his thirteen-year-old first cousin, Virginia Clemm. "I love, you know I love Virginia passionately devotedly. I cannot express in words the fervent devotion I feel towards my dear little cousin — my own darling," wrote the 26-year-old Poe in a letter to his aunt, begging for permission to marry her. "Ask Virginia. Leave it to her. Let me have, under her own hand, a letter, bidding me good bye — forever — and I may die — my heart will break — but I will say no more."9 Instead, Poe got the answer he wanted; the two cousins were married in Richmond, Virginia on 16 May 1836. Some have speculated that Edgar and Virginia Poe had an unusual relationship that was more like brother and sister than a married couple. But everyone who saw them together noted that they seemed loving and affectionate with one another. Whatever the workings of their marriage, it seemed to be a happy one. In 1837, Poe moved his family (which consisted of Virginia and her mother Maria Clemm, who lived with the couple) to Philadelphia. He soon published his first and only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. The publisher and Poe himself tried to pass off the fictional account of a whaling ship stowaway as a true story, a strategy that failed with the public. Also, the novel was not the best format for Poe's talent. In a favorable review of Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story collection, Twice Told Tales, Poe laid out his own argument for why short stories and narrative poems were the way to go. "The unity of effect or impression is a point of the greatest importance … this unity cannot be thoroughly preserved in productions whose perusal cannot be completed at one sitting," Poe wrote. "The ordinary novel is objectionable, from its length... As it cannot be read at one sitting, it deprives itself, of course, of the immense force derivable from totality."11 In other words, as soon as a reader sets a book aside, the effect of suspense or excitement is lost. The best stories let you keep that feeling straight through, from beginning to end. Poe proved his theories with the 1840 publication of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, a collection of short stories that included macabre classics like "Berenice" and "The Fall of the House of Usher." The book established Poe as a master of the short story form, then a popular type of entertainment that appeared regularly in newspapers and magazines. Poe then took a job at Graham's Magazine, which published his story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue." The story of detective C. Auguste Dupin was the world's first detective story, predating Sherlock Holmes. Poe spun off several more tales featuring the popular character, whom he described as "fond of enigmas, of conundrums, hieroglyphics; exhibiting in his solutions of each a degree of acumen which appears to the ordinary apprehension praeternatural." 12 Of course, Poe was also describing himself. Though he still struggled with money, things seemed to be looking up for Edgar Allan Poe. Then in January 1842, while singing at the piano, his wife Virginia began to bleed from the mouth—a symptom of tuberculosis. The dreaded disease that had killed his parents and his brother now seemed poise to strike his wife as well. Poe’s wife, Virgina Clemm EDGAR ALLAN POE: DEATH By 1845, Poe's family was living in New York City, where the writer was working at the New York Evening Mirror. The magazine published a long poem by Poe, entitled The Raven. "Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,/ Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,/ While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,/ As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door,"13the famous verses began. The poem was perfectly Poe—suspense that built steadily toward a dramatic end, the haunting specter of a lost love, the eerie presence of the supernatural. The Raven was wildly successful and remains Poe's most famous work. Within months of publication, just about everyone had read The Raven or heard it performed. It brought Poe the fame (but not financial success) that had so long eluded him. Sadly, The Raven was the pinnacle of Poe's life. It only went downhill from there. Poe had always wanted to own his own magazine so he wouldn't have to answer to a boss. The success of The Raven allowed Poe to realize his dream. He purchased the Broadway Journal, a publication already heavily indebted when Poe bought it. Though Poe solicited financial help with all the finesse of an e-mail scam artist ("I can [save the magazine] easily with a very trifling aid from my friends. May I count you as one? Lend me $50 and you shall never have cause to regret it," 14 read one such plea). But the magazine failed in January 1846. On 30 January 1847, Virginia Clemm died of tuberculosis at the couple's home in the Bronx. Poe was so distraught with grief that people thought he had gone insane. Poe denied it—"I was never really insane, except on occasions where my heart was touched,"15 he later said—but his wife's death sent him into a downward spiral of drinking and depression from which he would never recover. A problem drinker all his life, Poe now seemed to spin out of control. In the fall of 1848, Poe proposed marriage to the poet Sarah Helen Whitman, who agreed to marry him on the condition that he quit drinking. Poe couldn't get sober, and Whitman called off the engagement a month later. The next summer, Poe traveled to Richmond to convince his childhood sweetheart Elmira Royster Shelton to marry him. She accepted. Poe joined the Sons of Temperance, a social organization that forbade drinking (sort of like a nineteenth-century version of Alcoholics Anonymous.) Then in September, he traveled from Richmond to New York to raise money for a new magazine, stopping in Baltimore along the way. Poe arrived in Baltimore on 28 September 1849. No one knows how he spent the next few days. On 3 October 1849, Edgar Allan Poe was found in a Baltimore street (some reports say in a gutter), semi-conscious and wearing clothes that didn't fit him. He was taken to a hospital, where he spent four delirious days before perishing on 7 October 1849. He was 40 years old. No one knows exactly what happened to Edgar Allan Poe. Did he drink himself to death? Was he robbed and knocked unconscious? Did he have some other illness? Since he was found on an election day in politically corrupt Baltimore, one theory has it that Poe was "cooped." Political gangs would kidnap people and force them to change into different clothes so that they could vote at multiple polling sites. Victims were sometimes beaten or forced to drink alcohol to get them to go along with the plan. Others have suggested that "cooping" had nothing to do with Poe's death, proposing that the writer instead perished of (take your pick!) tuberculosis or heart disease or brain tumor or epilepsy or diabetes or drug overdose or carbon monoxide poisoning or even rabies. Unfortunately, we'll probably never know the true story. Poe's reputation was tarnished for years after his death, thanks to the efforts of his literary nemesis, Rufus Wilcot Griswold. Griswold was a former minister who had become an editor. Though the two men had worked together professionally, they deeply distrusted one another. Griswold thought Poe was immoral, and Poe thought Griswold was a literary lightweight. The two had a falling out when Griswold erroneously accused Poe of writing a brutal, anonymous review of an anthology that Griswold had edited. After Poe's death, Griswold tricked Poe's mother-in-law, Maria Clemm, into selling him Poe's papers and allowing him to be Poe's literary executor. His falsehood-filled biography of Poe was the only comprehensive "record" of the writer's life until Poe's friends fought back in the 1870s and wrote their own pro-Poe biography. With sources as biased as these providing so much of the evidence, it's no surprise that debate over the details of Poe's life and mysterious death continues today. Debate over Poe's legacy is much less fierce. The man whose life ended in the gutter is today hailed as a literary genius, the master of horror and inventor of detective fiction (and perhaps science fiction as well). The French were, perhaps surprisingly, among the first to love Poe, and many French writers (including Jules Verne, Charles Baudelaire, and Stéphane Mallarmé) were heavily influenced by him. Not surprisingly, Poe also influenced Sherlock-Holmes-creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, suspensemeister Alfred Hitchcock, weird-fiction-superstar H.P. Lovecraft, Gothic virtuosos William Faulkner and Joyce Carol Oates, contemporary horror maestros Clive Barker and Stephen King, and Russian kings-of-creepy Feodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Nabokov. Also on the list of the influenced are Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, and Charles Dickens. Even Sylvester Stallone is a fan, and is making a Poe movie. The list goes on and on, and is expanding even as we speak. So there's no question that Edgar Allan Poe's literary legacy is secure. But Poe the man, of course, is long gone, dead and buried in Baltimore. On his headstone is a raven that is sitting—still is sitting!—beneath the carved word "Nevermore," at the grave of one whose pen has been stilled forever more.