R WR E THANKS FOR COMING

advertisement

WR R

E

THANKS FOR COMING

“Difficult Texts”

A workshop with AFYE and WRAD, following

Tomorrow’s Professor, No. 1154

Sharon M. Klein

20 March 2012

Some other people whose ideas am likely to be using:

Dr. Mira Pak, Secondary Education; Dr. Kate Stevenson, Mathematics;

Dr. Irene Clark, English. The many others beyond the campus are with

us as we go—you’ll see references to them here, and on the handout.

“It seems very pretty,” she said when she had finished it,

“but it’s rather hard to understand!” (You see she didn’t

like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn’t make it out

at all.) “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I

don’t exactly know what they are!”

The Annotated Alice:Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,

Through the Looking Glass. Lewis Carroll, Introduction and notes by Martin Gardner.

New York, NY: Times Mirror. 1960.

Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey

California Alliance for Reading (CAR)

on November 7, 2008.

Ibid

http://cgi.stanford.edu/~dept-ctl/tomprof/posting.php?ID=1145

Deep reading v. Surface reading

Semantic memory

Connections, knowledge, visual images representing the content

“Transformative of one’s perspective […] involv[ing] long term comprehension”

Roberts and Roberts 2008, in Tomorrow’s Professor 1145

When experts read difficult texts, they read slowly and reread often. They

struggle with the text to make it comprehensible. They hold confusing

passages in mental suspension, having faith that later parts of the text may

clarify earlier parts. They "nutshell" passages as they proceed, often

writing gist statements in the margins. They read a difficult text a second

and a third time, considering first readings as approximations or rough

drafts. They interact with the text by asking questions, expressing

disagreements, linking the text with other readings or with personal

experience. p. 3, #2

Understanding the reading process—in the face of daunting text. Hey—what

makes text(s) daunting?

Not knowing what the text is for: “Why am I reading this?”

Not knowing how to adjust “reading strategies” and the

“reading process” (and what are those again?) to the

nature (genre?) and purpose(s) of the text.

“unfamiliarity with the text’s genre and the [rhetorical] function of that

genre within a discourse system” ….huh?

“Learning the rhetorical function [context, and structure—the argument] of

different genres takes considerable practice as well as knowledge of a

discipline's ways of conducting inquiry and making arguments. Inexperienced

readers do not understand, for example, that the author of a peer-reviewed

scholarly article joins a conversation of other scholars and tries to stake out a

position that offers something new. At a more specific level, they don't

understand that an empirical research study in the social or physical sciences

requires a different reading strategy from that of a theoretical/interpretive

article in the humanities. These genre problems are compounded further when

students are assigned challenging primary texts from the Great Books

tradition (reading Plato or Darwin, Nietzsche or Sartre, or an archived

historical document) or asked to write research papers drawing on

contemporary popular culture genres such as op-ed pieces, newspaper articles,

trade journals, blogs, or websites.” p. 4

“I don’t get this; it’s too hard.”

Is it “too hard?”

NO

What is a text?

Are we in a, er, relationship? What is it?

Do all texts have the same purpose?

"A memorandum is written not to inform

the reader but to protect the writer."

-- Dean G.Acheson

Should we talk about this in our classes?

Why not?

“cognitive egocentrism?”

“cultural literacy” {E.D. Hirsch)

“cultural capital?” Bordieu and Passeron 1973 and beyond

How about “funds of knowledge?”

http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/ncrcds01.html

cf., Oughton, Helen. 2010. Funds of

knowledge: A conceptual critique. Studies in

the Education of Adults, v42 n1 p63-78 Spr

2010

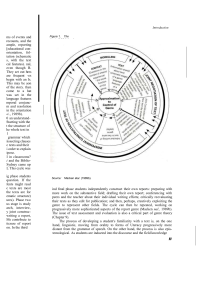

Reading models and their Implications:

All the pieces are part of the puzzle

Marilyn Jager Adams

Beginning to Read

MIT Press. 1990, p. 158

Rand Research brief: R&D program to improve

reading comprehension—a bigger picture

http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB8024.

html

Nash-Webber, Bonnie. 1975. The role of semantics in automatic

speech understanding. pp. 351-382. in Bobrow, Daniel G and

Allan Collins. Eds. Representation and understanding: Studies

in cognitive science. New York, NY: Academic Press, Inc.

Cited in Marilyn Jager Adams. 1998. Beginning to read: Thinking and

Learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 164

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2012/mar/20/springequinox-google-doodle?newsfeed=true

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/thenortherner/2012/mar/20/wenlock-edge-world-through-lambseyes

What we know and what is new—an important relationship in reading

This short video by Daniel Willingham is an excellent overview:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RiP-ijdxqEc

p. 259. Parker and Moore,

Critical Thinking, 10th ed.

McGraw Hill. 2012.

Some ways to use sentence structure. Imagine a lab report. One could use any of the

following:

As we look, notice that rewording and restructuring yields slightly different meanings—

critical reading makes writing more precise—and understanding the implications of

including or omitting words

Adapted from: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/683/01/

The pH level of the acid rose after the addition of

water

[what does this (not) say?]

The pH level of the acid was raised by adding water.

[uses the passive]

*I raised the pH level of the acid by adding water.

*I added water and it raised the pH level of the acid

Adding water raised the pH level of the acid.

The addition of water raised the pH level of the acid.

The acid’s pH level was raised by the addition of

water. [passive]

Added water raised the acid’s pH level.

http://www.optical-illusionpictures.com/ambig.html

http://www.yorku.ca/eye/necker.htm