Final report - Prostate Cancer UK

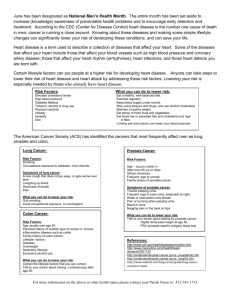

advertisement