Regression Analysis--2014 AAA Annual Meeting (ATL)

advertisement

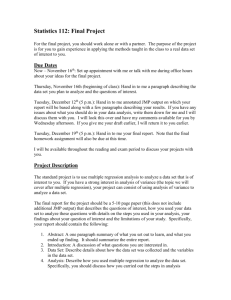

Regression Analysis— Instructional Resource for Cost/Managerial Accounting David E. Stout Lariccia School of Accounting & Finance 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association Effective Learning Strategies (ELS) Forum *Please Do Not Quote Without Permission of the Author* ABSTRACT The ability to generate accurate forecasts of costs is fundamental to the work of the managerial accountant. Experience of the author suggests difficulty on the part of managerial accounting and cost accounting students—graduate as well as undergraduate—in applying in an accounting context statistical concepts related to the use of regression analysis for cost-estimation purposes. This paper describes a classroom-tested instructional resource, grounded in principles of active learning and a constructivism, that embraces two primary objectives: one, “demystify” for accounting students technical material from statistics regarding ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression analysis—material that students may find obscure or overly abstract; and, increase student knowledge regarding the use of Excel for cost-estimation purposes. The resource consists of a set of seven PowerPoint slides, Word documents, and Excel files meant for distribution to students and divided into two major parts: four files that deal with simple (i.e., one-variable) linear regression, and three files related to the incremental unit-time learning-curve model. A separate Word file, meant for instructors, provides detailed guidance regarding the use of the student-based files. The resource is flexible in that it can be: used at both graduate and undergraduate courses in cost/management accounting; customized to meet the needs of individual instructors (coverage of the entire resource requires approximately 7 hours of in-class time); and, used in conjunction with any cost/management accounting textbook. Throughout the resource many references to related online supplemental materials are provided, including links to relevant online video clips. Survey evidence obtained from recent applications of the resource, in both undergraduate cost accounting and in MBA managerial accounting, indicates positive reception on the part of students: students perceive significant value in using the resource; the vast majority of students recommend continued use of the resource in future offerings of the course in question. Pre-test vs. post-test results from three classes over two recent semesters, though limited in scope, provide evidence of student learning. Keywords: Instructional resource Regression analysis Excel-based applications Cost/management accounting Cost estimation Page 1 of 18 1. Introduction Among foundational concepts in cost/managerial accounting, the topic of cost estimation is arguably the most important. Knowledge of cost behaviour, and the ability to provide relatively accurate estimates of cost, is related directly to the ability of a cost system to provide relevant data to support managerial functions of planning, control, and decision-making. In this sense, knowledge of cost behaviour and cost-estimation techniques may be considered of critical importance to the management accountant’s ability to add value to the organization. Students in cost/management accounting courses are typically exposed first to relatively simplistic methods of estimating cost functions, e.g., graphing (“eyeballing”) and the use of the “high-low” method.1 They then typically transition to a discussion of ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression as a “superior” method for estimating simple (i.e., one-variable) cost functions. Depending on time devoted by the instructor to the topic, students in cost/managerial accounting courses may be exposed to a variety of advanced considerations, including multiple-regression models, the use of dummy variables, and the estimation of learning-curve (i.e., non-linear) functions. Depending on the background of the instructor, various topics in regression analysis could be covered via available software, such as SPSS, Minitab, or Excel. By the time undergraduate accounting students cover cost estimation in a junior-level2 cost accounting class or by the time MBA students take a course in managerial accounting, they have typically had at least one statistics course, usually (but not always) taught by a faculty member outside of the business school. Over many years of teaching, I have observed that few of my students retain much from these classes beyond perhaps a vague notion or rudimentary knowledge of what “measures of central tendency” or “measures of variability” are. Even students who have in one or more statistics classes covered regression analysis and/or the use of a statistics package, seemed ill-equipped to apply this material in the courses I teach. There are, of course, exceptions. For example, some of my students who have taken one or more “business statistics” courses, which provide a context for covering basic statistical concepts, seem better prepared for the discussion of this material within the context of cost estimation and cost analysis, topics that—as noted above—can be considered fundamental to the managerial accountant’s toolkit. The “high-low” method fits a linear equation through two data points in a set of data: the high point in the data set and the low point. The slope coefficient (variable cost rate) is estimated first, as the change in total cost (Y) divided by the change in activity variable/cost driver (X) between these two points. The estimated slope coefficient (b) is then used to estimate the fixed-cost component (a) by subtracting from the total cost at either the high point or the low point the estimated variable cost. 1 In the U.S., “junior-level” refers to the third year of a typical four-year undergraduate (i.e., baccalaureate) degree program; “senior-level” refers to the fourth year of a four-year undergraduate degree program. 2 Page 2 of 18 Cost and management accounting textbooks in general do a very good job of covering what I would consider to be the basics of cost behaviour estimation and regression analysis. My sense, however, is that many of these authors view the topic as more under the purview of statistics professors than (cost or managerial) accounting professors. For this reason, coverage of regression analysis in cost/management accounting textbooks is, in my opinion, incomplete and superficial.3 For this reason, over the past few years I developed and class-tested, the instructional resource described in this manuscript. The rest of this paper is divided as follows. Section 2 contains an overview of the components of the learning resource. This is followed in Section 3 by a statement of the conceptual underpinnings and expected educational benefits of using this resource. Section 4 presents alternative implementation strategies that instructors might pursue in using the resource. Section 5 contains student assessment results (both direct and indirect) from two recent semesters in which the resource was used, while Section 6 provides a discussion of the limitations of the resource in terms of its scope. A short conclusion is offered in Section 7. 2. Overview This section provides an overview of an instructional resource that can be used—at both the undergraduate and graduate cost/managerial accounting level—to cover both the underlying theory behind ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression analysis and the use of Excel to estimate both simple linear and non-linear cost functions. As such, the resource is meant to complement available text material and can be used, at different levels of intensity, to reinforce and “demystify” technical statistical material to which students in upper-level (and MBA) managerial accounting classes may have been exposed to. The resource may be particularly valuable in situations where a textbook for the course is not required or where a textbook is used but with little-to-no coverage of material covered in this resource. The resource package consists of PowerPoint slides, Word documents, and Excel files, divided into two major parts: linear and non-linear cost-function estimation. These files, or userbased adaptations thereof, are meant for distribution to students. Coverage and use of the entire resource would consume approximately seven (7) hours of in-class meeting time, split between lecture-type (i.e., text) material and hands-on Excel-based work by the students. However, as I am cognizant of the argument some instructors in the area would make, to the effect that there are “more important topics” to cover. This, of course, is a judgment call. The critique referenced above in no way is meant to denigrate an alternative viewpoint regarding the importance of cost estimation, regression analysis, and the use of Excel in this regard, relative to other cost/management accounting-related topics. Those instructors who desire relatively minor coverage of these topics will likely find the material in existing cost/managerial accounting texts to be sufficient for their needs. As will be argued, instructors who desire more in-depth coverage of these topics should find significant value in the present instructional resource, including the set of files available on request from the author. 3 Page 3 of 18 noted above, the resource has built-in flexibility: based on the instructor’s goals and available time in the course, individual components of the resource package could be used.4 An overview of the seven files comprising the entire two-part instructional resource, along with estimated inclass coverage time for the material in each file, is provided in Exhibit 1. A supplemental file for instructors, “Reference Document (Regression Analysis—Instructional Resource),” provides a detailed discussion of the content of the seven student-related files as well as tips and recommendations for using these files in class. 5 This supplemental file complements the overview provided herein. --Insert Exhibit 1 here— As indicated in Exhibit 1, Part One deals with the use of regression analysis to estimate simple linear cost functions, the use of Excel for estimating these functions, interpretation of regression-related output associated with cost estimation, and alternatives for estimating costs based on a regression model fit to a set of data. This portion of the resource consists of the following four files: (1) a set of PowerPoint slides (“Estimating Linear Cost Functions”) that provides an overview of simple (one-variable) cost functions and OLS regression analysis; (2) an Excel file (“Estimating Linear Cost Functions Using Excel”) that discusses five Excel-based methods that can be used to estimate a simple linear cost function; (3) a Word file (“Cost Estimation and Statistical Issues—Regression Analysis”) that addresses three separate costestimation and statistical issues (five options in Excel for generating cost estimates after a regression analysis has been performed; an analysis of changes in the standard error of the regression, SE, as sample size, n, changes; and, constructing confidence intervals around point estimates); and (4) an Excel file (“Change in SE as n increases”) that can be used in conjunction with item (3) above. Part Two of the resource module deals with estimating one form of non-linear cost function: the incremental unit-time learning-curve model. This portion of the instructional resource consists of the following three files: (1) a PowerPoint file (“Estimating Learning-Curve Cost Functions”), which provides a review of logarithms and a discussion of common forms of learning-curve models; (2) a Word file (“Example—Estimating a Learning-Curve Function”), which provides a discussion of two procedures that can be used within Excel to estimate a learning-curve model; and (3) an Excel file (“Learning-Curve Analysis [“Incremental Unit-Time Model]), which provides a worked example of using Excel to fit a learning-curve model to a set of data and a basis for discussing the interpretation and use of the estimated coefficients in this model. 4 Implementation alternatives are discussed in Section 4, below. 5 All eight of these files are available on request from the author. Page 4 of 18 3. Conceptual Underpinnings/Anticipated Benefits to Students6 Most (but not necessarily) all students in our accounting classes have been exposed to the regression analysis and related statistical concepts (e.g., measures of dispersion or measures of central tendency). Some might also have been exposed to the use of Excel as a cost-estimation tool. Why, then, the need for coverage of these topics in an accounting class? Although the underlying cause of this situation is likely multidimensional, one plausible explanation is that many of our students may have adopted in their earlier studies what might be characterized as a “shallow” (or “surface”), rather than a “deep,” learning approach.7 The importance of the above-referenced distinction rests on the assumption that students do not have a fixed approach to learning; rather, it is the design of a learning opportunity that motivates students to embrace a particular approach to learning. While there are alternative strategies for motivating students to embrace a deep learning approach, one strategy is to use interactive assignments, similar to the instructional resource discussed in this paper. Put differently, because the present resource requires students to be actively (rather than passively) engaged in the learning process a deeper (conceptual) understanding of the material is possible.8 4. Implementation Alternatives and Usage Strategies The regression resource can be used in alternative ways. Below some thoughts are offered regarding alternative usages based both on level of class/background of students and on the textbook used by the professor. As noted earlier, the resource is very flexible and can be customized (expanded upon or reduced in length) to meet the needs of individual instructors. Thus, the thoughts below are meant to be suggestive in nature. 4.1. Alternative strategies based on course level and background of students I have used Part One (simple linear regression) of the module at both the undergraduate (cost accounting) and graduate (MBA managerial accounting) levels. In both cases, prior to in6 The author gratefully acknowledges an anonymous reviewer for comments that motivated the addition of this section to the paper. 7 In a surface approach, students focus principally on the ability to reproduce material on a test or an exam. By contrast, understanding of material is the primary aim of a deep approach to learning. Deep learning can lead to long-term retention of concepts, which can be used for problem-solving in unfamiliar contexts. In a deep approach to learning, the student analyses new facts and ideas critically, ties information into existing cognitive structures, and makes links between ideas and facts. Active learning is ultimately derived from what is called the “constructivist” approach to learning, that is, a belief that learning occurs when students are actively involved in a process of meaning and knowledge construction, as opposed to passively receiving information (e.g., traditional lecture format). In a “constructivist” classroom, students are afforded the opportunity of testing, exploring, investigating, etc.; the principal role of the instructor is facilitator. In short, constructivist teaching fosters critical thinking and motivated, independent learners. 8 Page 5 of 18 class coverage of the materials, files from the resource are made available to students via Blackboard. At both levels, one full week (either two 75-minute day sessions or one 2 hour and 40-minute evening session) was devoted to the resource. I begin by presenting in class the entire set of PowerPoint slides associated with Part One. Afterwards, I transition to the Excel file “Estimating Linear Cost Functions Using Excel,” which contains five alternatives for implementing regression analysis in Excel; all five methods are applied to the data set provided at the top of the Excel file. I generally focus the discussion on method #2 (use of the Regression routine in Excel), since this method provides opportunity for the most comprehensive discussion of regression-related output. I then transition to the Word document “Cost Estimation and Statistical Issues—Regression Analysis” and make sure that I cover at least one of the five options for generating cost estimates from the regression-related cost functions. At the undergraduate level, this typically concludes the discussion. At the MBA managerial accounting level, I try to cover (in addition to the material discussed above) the topic of constructing confidence intervals around point estimates generated by a regression equation. If covered, this typically concludes the one-night presentation to my MBA students. I have implemented the preceding plan successfully over the past five or six years. I recognize, however, that alternative implementation strategies exist, based both on the quality and background of students in the program and on the time the professor devotes to the module. For example, in situations where the students (at either level) have better backgrounds in terms of regression and the use of Excel to estimate cost functions, the deck of PowerPoint slides could be reduced in length and nothing more than a quick “refresher” or review devoted to the process of using Excel to generate cost estimates based on a regression model. In this situation, discussion could focus on supplementary issues covered in Part One (analysis of changes in SE as n [the sample size] changes and/or constructing confidence intervals around point estimates generated by a regression-based cost model). Alternatively, after a quick review of some of the material from Part One (based on the assumed knowledge and background of students), the instructor may focus on the material in Part Two: learning-curve functions and how such functions can be estimated using Excel.9 This plan might also be appropriate for students in an alternative graduate course, for example, a course on “Strategic Cost Management” taken by students in a Masters of Accountancy (MAcc) program. It is possible to cover both Part One (simple linear regression) and Part Two (learningcurve analysis) of the module. In this case, the instructor could expect to devote up to seven (7) hours of in-class time for the module. As noted earlier, flexibility is built into the module: the instructor has the ability to customize the files by adding to or subtracting from the material presented therein. If Part Two of the module is covered, and time permits, the case by Stout and Juras (2009) could be assigned. Finally, should the instructor desire to do so, the material in Part 9 The educational case by Stout and Juras (2009) could also be assigned in conjunction with Part Two of the resource. Page 6 of 18 Two could be extended to covering topics beyond those included in the module. For example, the module could be extended by covering the use of Excel for estimating and using multipleregression models of cost behaviour. In this case, the references provided below (in section 7) should be helpful. 4.2. Alternative strategies based on textbook used An examination of selected cost/management accounting textbooks reveals diversity in terms of coverage of regression analysis and the use of Excel to estimate regression functions and to use such functions for cost-estimation purposes. Exhibit 2 provides an overview of this coverage. –Insert Exhibit 2 here— As seen from Exhibit 2, coverage of regression-related (including Excel-based) topics varies from minor to no coverage (Datar and Rajan, 2014; Garrison et al., 2012; Hilton, 2011; Maher et al., 2012; Noreen et al., 2014; and, Atkinson et al., 2012) to what might be considered moderate/intermediate level coverage (Blocher et al., 2013; Horngren et al., 2012; and, Lanen et al., 2011).10 Given coverage in popular textbooks, a legitimate question is whether and to what extent the present instructional resource adds value. The author asserts that this resource has wide applicability and can be used (albeit in different ways) in conjunction with virtually any cost/managerial accounting text, as explained below. As indicated by the notes provided in Exhibit 2, even when there is topical overlap between textbooks and the present resource, textbook coverage can be considered relatively light.11 For example, only the REGRESSION routine in Excel provides a full complement of regression-related statistics. The last column in Exhibit 2 indicates that most cost/management accounting texts do not discuss this approach.12 Further, even for those texts that do present the REGRESSION routine as the method for estimating cost functions, there is very little (if any) discussion of the supplementary regression-related output. As demonstrated above, the present instructional resource provides a rich (and class-tested) discussion of this material within an accounting context, thereby attempting to “demystify” this material for business and accounting Classifications based on the author’s subjective assessment, based principally on the coverage dimensions (columns) reflected in Exhibit 2. 10 11 This statement should not be construed as criticism of available textbooks, which by design or necessity are limited in scope and coverage of some topics relative to others. The primary point is that the present instructional resource extends and therefore adds value to the regression-related (including Excel-related) material contained in popular cost/management accounting textbooks. It is, in fact, the reason that the resource was developed in the first place. 12 It is interesting, too, that only one of the texts reviewed in Exhibit 2 (Blocher et al. 2013) discusses the issue of building confidence intervals around point estimates generated by regression functions. Page 7 of 18 students. Further, as indicated in Exhibit 2, coverage of the use of Excel for both cost-estimation and cost-prediction purposes is relatively light compared to coverage contained in the present instructional resource.13 Finally, even when there is textbook coverage of Excel, the discussion is limited: the present instructional resource provides a rich set of alternatives in terms of using Excel to generate cost functions (both linear and non-linear) and for using these functions for cost-estimation purposes. Thus, the resource should be particularly attractive in those cost/managerial accounting courses in which a heavy emphasis on Excel is placed. In those classes where a textbook is not required, the module could be used as primary source material for student learning of cost estimation using regression analysis, the use of Excel for cost-estimation purposes, interpretation of regression-related output, and the use of Excel for cost-prediction purposes.14 In situations where a textbook is used, the incremental value of the module is a function of what is available in the textbook used by the instructor relative to the goals of the instructor and the amount of available class time. Exhibit 2 is helpful in guiding the discussion in this regard. As noted both by Exhibit 2 and the discussion above, in virtually all cases (but to varying degrees) the present instructional resource provides a useful supplement to the material covered in popular cost/managerial accounting textbooks. 5. Student Feedback Student feedback in two forms was obtained: responses to a 12-item survey instrument created by the author and administered to students, and scores on a five-item set of multiplechoice questions constructed by the author and administered by the author both prior to and subsequent to in-class coverage of the material.15 The former provides indirect evidence regarding the efficacy of the regression module, while the latter provides more direct (albeit limited) evidence of student learning. 5.1. Survey response data 13 It is interesting to note that the perennial market leader in the cost accounting area (Horngren et al., 2012) has no instructional material regarding the use of Excel for cost-estimation and/or cost-prediction purposes. As Exhibit 2 notes, a mathematical formula for estimating the slope and intercept of a linear cost function are presented (p. 367). The text includes no discussion of the use of Excel, although the discussion does make reference to “output from Excel.” 14 The text used by the author in MBA managerial accounting is Atkinson et al. (2012). As noted in Exhibit 2, this text has no coverage of regression-based cost estimation and cost prediction, including Excel-based material. In this course, therefore, the instructional resource discussed herein serves as the primary learning tool for this material. 15 The pre-test was administered during the first week of class. The regression instructional resource was covered during the third week of class. The 12-item student survey (see Table 1) was administered after coverage of the regression material but the week before the administration of the post-test. The post-test was administered to students at the beginning of the fifth week of class, as part of an in-class exam that included additional material covered during the first four weeks of class. Page 8 of 18 Students responded to the survey instrument using a five-point Likert-type scale, with 1 = “strongly agree” and 5 = “strongly disagree.” Response data for Fall semester 2013 (MBA managerial accounting, n = 20, and undergraduate cost accounting, n = 25) and Spring semester 2014 (MBA managerial accounting, n = 31) are presented in Table 1. A comparison of responses to Q11 and Q12 compared to Q1 and Q2 indicates an increase in perceived knowledge of both regression concepts and the use of Excel to estimate regression functions.16 Responses to Q3 and Q4 indicate a perception that the resource was effective in illustrating both important concepts regarding regression analysis and the use of Excel for cost-estimation purposes. Responses to Q5, Q6 (reverse-scored), and Q7 indicate that student in all three classes found value in the material. Virtually all students in these classes agreed or strongly agreed that coverage of the regression module was an effective use of class time (Q5) and that the material should be used in future offerings of the course (Q7). Note that the wording of Q6 was reversed: the vast majority of students disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that the regression resource did not increase knowledge and understanding of regression.17 Items Q8 through Q10 were included to help improve the measurement properties of the survey instrument: the present regression resource has nothing to do with constructing a “profit-planning model” (Q8)18 or with “decisionmaking under uncertainty” (Q10). And since only Part One of the resource (simple linear cost functions) was covered in these classes, there is no reason to expect a positive response to Q9, which refers to “a better understanding of learning-curve functions.” Low scores on items Q8 through Q10 were therefore anticipated. As seen in Table 1, responses to each of these items indicate little-to-no perceived effect of the learning resource on each of these three dimensions. —Insert Table 1 here— 5.2. Pre- versus post-test results At the beginning of the semester, the set of five regression-related multiple-choice items constructed by the author (see the Appendix) was administered to students as a pre-test. The same items were subsequently included on an in-class exam administered during week five of the course. The exam included all material covered during the first four weeks of the course, including the regression-related material covered in week four. Five-item aggregated pre-test versus post-test results, from both MBA managerial accounting classes (Fall semester 2013 and Spring semester 2014) and undergraduate cost accounting (Fall semester 2013) are reported in 16 As seen from the data in Table 1, roughly 70-80% of students perceived that prior to coverage of the regression module their knowledge of regression fundamentals (Q1) and the use of Excel to estimate regression functions (Q2) was “very minimal.” However, 80% or more of students in the sampled indicated a perception that, after covering the regression module, their knowledge of regression concepts (Q11) and knowledge of the use of Excel to estimate regression functions (Q12) was “very good.” The extent to which knowledge of regression concepts increased is addressed, albeit in limited fashion, by the results reported in Table 2 below. 17 This is a common approach to guarding against (or detecting) response-set bias. 18 In my classes, CVP analysis (short-term profit planning) is covered after coverage of the topic of cost estimation/regression analysis. Page 9 of 18 Table 2, Panel A. As can be seen, there were statistically significant increases in mean scores and a slight reduction in the score variability (measured by sample standard deviations) for all three groups. Panel B in Table presents paired-sample t-test results for mean differences on each of the five items (both under the assumption of equal and unequal variance in scores, pre-test vs. posttest). As can be seen, these results are generally (but not wholly) consistent with the five-item aggregate-level results reported in Panel A. --Insert Table 2 here— While the data reported in Table 2 are consistent with a positive effect of the resource on student learning, caution in interpreting these results is in order, for three reasons: one, data are from a single semester at a single institution; two, only a subset of items covered in the instructional resource were included on the test (i.e., the resource is much richer in terms of content coverage—we simply do not have assessment results for these other learning dimensions, such as the many Excel-based applications in the module); and three, there is no comparison group, that is, no claims can be made regarding the effect of the learning resource relative to other mechanisms for covering regression-related material. It is entirely possible that greater (or lesser) levels of test-item scores would be observed through use of an alternative resource. 6. Limitations and Extensions While the author believes the present resource for regression analysis is rich, there are certain important topics that are not covered. For example, the discussion of learning-curves (in part two of the module) did not consider the cumulative average-time model. The extension of the discussion to cover this topic is, however, straightforward. The instructor who wishes to cover this alternative form of the learning curve model can use the same data set provided in the Excel data file. Another limitation relates to the focus of use of only a single approach for cost-estimation purposes: fitting past observations to a function using regression analysis. As noted in Hilton (2011, p. 251), Lanen et al. (2011, pp. 156-158), and Garrison et al. (2012, p. 35), non-statistical approaches (such as account analysis and the engineering method), can be used for costestimation purposes. Thus, instructors using the present regression resource should make the point to students that this statistical approach is but one of several available alternatives that can be employed in practice. In addition, the resource does not include coverage of several important regressionrelated topics, such as the use of dummy variables, the problem of statistical “outliers” (i.e., abnormal data observations), dealing with trend and/or seasonality in time-series regressions, and the estimation of multiple-regression models of cost behaviour. At the same time, the foundation provided by the present instructional resource should allow for a smooth transition to these Page 10 of 18 topics, should the instructor be inclined to do so. In addition to material found in cost/managerial accounting textbooks, much information regarding these topics is available on the web. For example, the instructor who wishes to cover the use of Excel to generate multiple-regression models can have students consult any of the following sources: http://www.wikihow.com/Run-a-Multiple-Regression-in-Excel http://www.real-statistics.com/multiple-regression/multiple-regression-analysis/ http://www.jeremymiles.co.uk/regressionbook/extras/appendix2/excel/ Pertinent video clips covering the topic of multiple-regression analysis and using Excel to estimate multiple-regression models are available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHVL6aCpf2g http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2J8WBo2CKM4 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ek4bIe-DuMA http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tlbdkgYz7FM http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IL7xukTdLyI http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HgfHefwK7VQ 7. Conclusion Knowledge of cost behaviour is of fundamental importance to the areas of cost and managerial accounting. Cost estimates, drawn from cost equations (or models), are used for managerial functions related to planning, control, and decision-making. As such, one can make the argument that in accounting curricula today extensive coverage of material related to the cost-estimation process (including regression analysis and the use of spreadsheet software, such as Excel, for this purpose) is appropriate, if not desirable. Experience of the author over many years, at both the graduate and undergraduate levels of cost/managerial accounting, suggests that many (if not most) students have difficulty applying to an accounting context regression-related material covered in statistics classes. This paper discusses a classroom-test instructional resource that has two primary objectives: “demystify” technical material regarding regression and related statistical concepts both by providing contextual richness to the discussion; expose students to an extensive array of Excel-based tools and functions related to use of regression analysis for estimating cost functions. The module is grounded conceptually in a constructivist/active-learning approach. The resource is divided into two major sections: Part One deals with the estimation of simple (i.e., one-variable) linear functions, while Part Two deals with the estimation of one type of learning-curve (i.e., non-linear) function. The material contained in the module is designed to supplement current textbook coverage of regression and the use of Excel for cost-estimation Page 11 of 18 purposes. The entire resource consists of eight files, all of which are available on request from the author. Extensive references to additional source material—both in print and in video-clip form—are provided in a Word document for instructors named “Reference Document (Regression Analysis—Instructional Resource)” and throughout the resource six files meant for distribution to students. The instructional resource discussed herein can be used at either the undergraduate (e.g., cost accounting) level or in an MBA managerial accounting class. Approximately two weeks of class time (roughly six hours) would be needed to cover the entire resource. The resource is flexible, however, and can be customized to meet the needs of individual faculty. Alternative implementation strategies for the resource, based on the goals of the instructor, the amount of class time available, and the textbook used in the course in question are possible. Feedback, from both undergraduate cost accounting and MBA managerial accounting students, regarding the module has been positive: students generally perceive that coverage of the module increases both their knowledge of regression and their proficiency in using Excel to do regression analysis. The vast majority of students who recently covered the module recommended that the module be used in future offerings of the course in question. To complement the discussion of simple (single-variable) models covered by the present resource, references to multiple-regression models and the use of Excel to estimate such models—topics not covered in the resource—are provided at the end of the paper. References Anderson, D. R., D. J. Sweeney, and T. A. Williams. (1987). Statistics for Business and Economics, 3rd edition. New York: West Publishing Company. Atkinson, A. A., R. S. Kaplan, E. M. Matsumura, and S. M. Young. (2012). Management Accounting: Information for Decision-Making and Strategy, 6th edition. New York: Pearson. Blocher, E. J., D. E. Stout, P. E. Juras, and G. Cokins. (2013). Cost Management: A Strategic Emphasis, 6th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Datar, S. M. and M. V. Rajan. (2014). Managerial Accounting: Making Decisions and Motivating Performance. New York: Pearson. Garrison, R. H., E. W. Noreen, and P. C. Brewer. (2012). Managerial Accounting, 14th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Hilton, R. W. (2011). Managerial Accounting: Creating Value in a Dynamic Business Environment, 9th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Page 12 of 18 Horngren, C. T., S. M. Datar, and M. Rajan. (2012). Cost Accounting: A Managerial Emphasis, 14th edition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. Lanen, W. N., S. W. Anderson, and M. W. Maher. (2011). Fundamentals of Cost Accounting, 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Leininger, W. E. (1980). Quantitative Methods in Accounting. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company. Maher, M. W., C. P. Stickney, and R.Weil. (2012). Managerial Accounting: An Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses, 11th edition. South-Western, Cengage Learning. Noreen, E. W., P. C. Brewer, and R. H. Garrison. (2014). Managerial Accounting for Managers, 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Stout, D. E., and P. E. Juras. (2009). Instructional case: Estimating learning-curve functions for managerial planning, control, and decision-making. Issues in Accounting Education, Vol. 24, No. 2 (May), pp. 195-217. Page 13 of 18 Table 1 Student Feedback—Survey Results: Fall Semester 2013 and Spring Semester 2014 Item Q1. Prior to this course, my knowledge of regression concepts was very minimal. Q2. Prior to this course, my knowledge of the use of Excel to estimate regression functions was very minimal. Q3. The regression resource used in this class was effective in terms of illustrating important concepts associated with regression analysis. Q4. The regression resource used in this class was effective in terms of illustrating the use of Excel to estimate regression functions. Q5. Coverage of the regression resource in this class was an effective use of my time. Q6. The regression resource did NOT increase my knowledge and understanding regression analysis. Q7. I would recommend the use of the regression resource in future offerings of this course. Q8. After completing the regression resource, I am now better able to construct a profit-planning model. Q9. After completing the regression resource I have a better understanding of learning-curve functions. Q10. Use of the regression resource has increased my understanding of decision-making under uncertainty. Q11. My knowledge of regression concepts is very good. Q12. My knowledge of using Excel for estimating regression functions is very good. Fall Semester 2013 Undergraduate Cost MBA Managerial Accounting (n = 25) Accounting (n = 20) % Agree/ % Agree/ Mean Strongly Mean Strongly (Median) (Median) Agree Agree 2.10 75 2.25 80 (2.00) (1.50) 1.75 75 2.00 70 (2.00) (1.50) 1.60 100 1.50 100 (2.00) (1.00) 1.80 100 1.58 100 (2.00) (1.50) 1.60 90 1.58 100 (1.50) (2.00) 4.10 8 4.25 0 (4.00) (4.00) 1.80 100 1.50 100 (2.00) (1.00) 3.75 12 4.00 5 (4.00) (4.00) 3.50 12 3.75 10 (4.00) (4.00) 3.75 8 4.25 5 (3.50) (4.00) 1.85 80 1.80 90 (2.00) (2.00) 1.70 90 1.50 100 (2.00) (2.00) Legend: (1) = Strongly Agree, (2) = Agree, (3) = Neutral, (4) = Disagree, (5) = Strongly Disagree Spring Semester 2014 MBA Managerial Accounting (n = 31) % Agree/ Mean Strongly (Median) Agree 2.25 71 (2.00) 1.75 77 (1.75) 1.70 100 (1.75) 1.45 100 (1.50) 1.50 97 (1.50) 4.25 6 (4.00) 1.50 97 (1.00) 4.10 9 (4.00) 3.60 9 (4.00) 3.75 13 (4.00) 1.60 90 (1.50) 1.75 97 (2.00) Table 2 Panel A: Five-Item Aggregate Pre-test vs. Post-test results: Fall Semester 2013 and Spring Semester 2014 Statistic Mean Median SD Fall Semester 2013 MBA Managerial Paired-Sample t(n = 20) test Pre-test Post-test p* df** 0.40 0.68 < 0.0001 19 0.40 0.70 0.23 0.16 Fall Semester 2013 Undergraduate Cost (n = 25) Pre-test Post-test 0.50 0.70 0.60 0.80 0.19 0.13 Paired-Sample ttest p* df** < 0.0001 24 Spring Semester 2014 MBA Managerial (n = 31) Pre-test Post-test 0.47 0.74 0.60 0.80 0.21 0.17 Paired-Sample t-test p* df** < 0.0001 30 * Based on a two-tailed distribution **df = n −1 Panel B: Individual Item Analysis—Pretest vs. Post-test Results: Fall Semester 2013 and Spring Semester 2014 Question #* 1 2 3 4 5 Fall 2013: MBA Managerial (n = 20) p-value on mean difference** Equal variance Unequal variances 0.048 0.058 0.015 0.011 0.035 0.013 0.048 0.060 0.086 0.060 Fall 2013: Undergraduate Cost Accounting (n = 25) p-value on mean difference Equal variance Unequal variances 0.052 0.094 0.067 0.071 0.055 0.045 0.106 0.132 0.015 0.045 Spring 2014: MBA Managerial (n = 31) p-value on mean difference Equal variance Unequal variances 0.001 0.003 0.009 0.013 0.022 0.021 0.016 0.034 0.052 0.021 *See Appendix. **Based on a two-tailed distribution. Page 15 of 18 Exhibit 1: Overview of Resource Components Part One: Estimating Simple Linear Cost Functions File Type File Name PPT Estimating Linear Cost Functions Estimating Linear Cost Functions Using Excel Cost Estimation and Statistical Issues— Regression Analysis Change in SE as n increases Excel Word Excel Estimated InClass Time Description Introduction/Overview of Simple (One-Variable) Cost Functions and OLS Regression Five Excel-Based Methods for Estimating a Simple Linear Cost Function Cost-Estimating Procedures using Excel (Five Options); Analysis of Changes in the SE as n (Sample Size) Changes; Constructing Confidence Intervals Around Point Estimates Analysis of How the Standard Error of the Regression (SE) Can Change/Be Improved 0.75 hour 1.75 hours 1.50 hours 0.5 hour Total 4.50 hours Part Two: Estimating a Learning-Curve Function File Type PPT Word Excel File Name Estimating LearningCurve Cost Functions Example—Estimating a Learning-Curve Function Learning-Curve Analysis (“Incremental Unit-Time Model”) Description Introduction (Review of Logarithms and Common Forms of Learning Curves) Overview of Two Procedures in Excel for Estimating the “Incremental Unit-Time Model” Using Excel to Fit a Learning-Curve Model to a Data Set Total Estimated InClass Time 0.75 hours 1.00 hours 0.75 hours 2.50 hours Exhibit 2: Overview of Selected Textbook Coverage of Regression Analysis and Use of Excel by Subjective Assessment of Extent of Coverage Panel A: Slight (or No) Coverage Text Atkinson et al. (2012) Datar and Rajan (2014) Topical Coverage R SE MR LC 2 X X Excel Coverage CE CP MR LC X Garrison et al. (2012) X X Hilton (2011) X X X Maher et al. (2012) X X X Noreen et al. (2014) X X Notes MR and LC given very light coverage Excel material covered in Appendix 2A (pp. 67-69); INTERCEPT, SLOPE, and RSQ functions in Excel covered Excel material covered in Appendix to Chapter 6 (pp. 256-257); INTERCEPT, SLOPE, and RSQ functions in Excel covered LC analysis covered in Appendix 5.1 (pp. 160-161) Excel material covered in Appendix 2A (pp. 64-66); INTERCEPT, SLOPE, and RSQ functions in Excel covered Panel B: Moderate/Intermediate-Level Coverage Text Topical Coverage R SE MR LC Blocher et al. (2013) X X X X Horngren et al. (2012) X X X X Lanen et al. (2011) X X X 2 Excel Coverage CE CP MR LC X X Notes Confidence intervals covered; REGRESSION routine covered; six-page online supplement covering regression-related output is available Regression formula, not functions in Excel, used (footnote 3, p. 367), although reference is made to “output from Excel” Use of REGRESSION routine in Excel covered in Appendix 5A (pp. 175-180); learning-curve functions covered in Appendix 5B (pp. 180-181) Legend: SE=standard error of the regression; MR = multiple-regression; LC = learning-curve functions; CE = cost-function estimation; CP = cost prediction (from a regression equation). Appendix: Test Items 1. OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression: (A) Cannot be used to estimate nonlinear cost functions, such as learning-curve functions (B) Cannot handle multiple cost drivers (independent variables) (C) Assures us of the “line of best fit” using the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) criterion (D) Is sensitive to outliers (abnormal data points) because of the “squaring” procedure that is used for cost-estimation purposes (E) None of the above is correct 2. In estimating cost functions, including linear cost functions, the analyst can calculate a statistic referred to as the “coefficient of determination” (that is, R2). This statistic refers to: (A) The percentage variation in cost, Y, that can be explained by the variation in the independent variable, X (e.g., units produced) (B) The slope of the cost function at the highest point on the curve (C) The amount of variance in cost, Y, that is not explained by the output variable, X (D) An amount equal to “1 minus the explained variation in Y given changes in X” (E) None of the above 3. The standard error of the regression (SE): (A) is an absolute measure of “goodness-of-fit” for a cost function (B) is equal to the sum of the squared deviation between each Y value and the mean of the Y’s (C) cannot be calculated for cost functions containing more than a single independent variable (D) represents the estimated value of Y when X (the independent variable) is zero (E) is defined as 1 – R2 (where R2 = the coefficient of determination) 4. Regression analysis can be used, with past (historical) observations, to estimate linear cost functions. In what sense does OLS regression analysis result in the line of best fit through any set of data points? (A) It minimizes the variance of the actual observations around the mean value of Y (B) It disregards sunk costs when calculating an estimate of the fixed cost component (C) It minimizes the sum of the squared deviations of the actual observations around the mean value of Y (D) It smooths out the effect of atypical or abnormal observations (E) None of the above 5. The standard error of the regression (SE) is best interpreted as: (A) the estimated slope coefficient of a linear cost function (B) the estimated slope coefficient of a non-linear cost function (C) the percentage of the variability of the dependent variable (e.g., cost) associated with changes in the cost driver (activity variable) (D) a relative measure of goodness-of-fit between the dependent variable and the independent variable in a regression equation (E) None of the above