Date - King`s College London

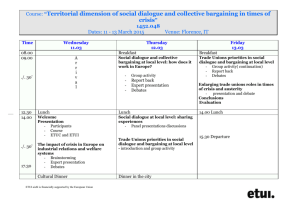

advertisement