Music Therapy and Pain Management

advertisement

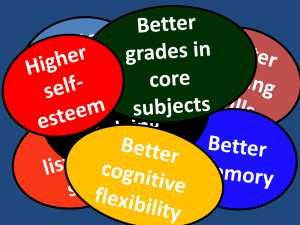

Music Therapy 1 Music Therapy and Pain Management Sophie Krefft October 1, 2010 Background Music Therapy Music therapy is a health profession in which the therapist combines musical interventions with a supporting relationship and seeks to improve the well-being of his or her clients (http://www.musictherapy.org/). There are numerous goals musical therapy can seek to accomplish, namely the management of pain, reduction of stress and anxiety, alleviation of depression, treatment of respiratory problems, exercising of joints and limbs, provision of control and self expression, and general promotion of good health (Bailey, 1986; http://www.musictherapy.org/). The most common treatment methods of music therapy are listening to music, singing, dancing, and creating music (http://www.musictherapy.org/). The relief of pain is a primary focus of music therapy, and numerous studies have proven it to be effective for alleviating acute pain (Bailey, 1986; Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963; Michel & Chesky, 1995; http://www.musictherapy.org/). Pain There are two different kinds of pain: acute and chronic. Acute pain is sudden but temporary pain, Music Therapy 2 whereas chronic pain endures for a long time, even years. Pain is a signal of suffering in one or multiple domains (physical, emotional, etc.) and its experience is highly subjective (Maslar, 1986). How intensely pain is experienced and the level it can be tolerated at depends on several factors. Expectations of pain levels, suggestion of how well the treatment will work, mood of the patient (especially the presence of anxiety or stress), amount of focus on the pain, and intensiveness and duration of the pain, as well as early childhood experiences and culture can all impact how an individual encounters pain (Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague). Initially, the pain is fought naturally by the body’s release of endorphins, a type of neurotransmitter. If the pain persists, it is typically treated with pain medication, but it can also be treated by alternative techniques, which is where music therapy comes into play (Maslar, 1986). Music Therapy and Pain Management Goals and Methods Music therapy is generally used to reduce pain when medication does not provide adequate relief, in which case the therapy is combined with drug use. Another reason for using music is when pain medications cause serious side effects in a patient and so cannot be used (http://www.musictherapy.org/). When music therapy is employed for pain management, its goals are to increase the patient’s comfort, wellbeing, and feeling of control over pain (Bailey, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, Sprague, 1963; http://www.musictherapy.org/). The aforementioned methods of music therapy, with the exception of dancing, can all be applied when the therapy’s focus is pain, and which Music Therapy 3 method is chosen depends on the patient’s needs, experience with music, and coping abilities. Regardless of the method chosen, communication between the therapist and the patient is vital, both to allow the patient to participate in the selection of music and to discuss the emotions and thoughts the music elicits (Bailey, 1986). In Bailey’s review of music therapy in 1986, she said that a music therapist can usually categorize a client’s experience with music into one of three genres: performer, listener, or “event-er” (p. 26). A performer is defined as a person who has practiced creating their own music, either by singing, playing an instrument, or composing music. Anyone who has spent time keenly listening to music is classified as a listener. Lastly, an event-er is described as a person whose only interaction with music is when it is incorporated into another event, such as a wedding. All three of these groups can benefit from listening to music, although they can all be given different tasks – performers are told to sing or play along, listeners are told to listen and critique, and event-ers are told to visualize people, places, and events to go along with the music. Furthermore, performers can create their own music to go along with what they are hearing. As a general rule, the music chosen for therapy should be harmonious, steady, gentle, and relaxing. Instrumental music is the most widespread choice, although music that incorporates singing is still substantially used (Bailey, 1986). The iso-principle is a rather common method of music selection and is based on the idea of slowly converting the patient’s mood from its present state to a more desirable one (Maslar, 1986). First Music Therapy 4 music is found that matches the patient’s emotional state (be it lonely, fearful, etc.), and then it is gradually modified until the songs being played are cheerful and comforting and the patient’s disposition is the same (Bailey, 1986). Other factors can also influence what music is chosen, such as the patient’s coping abilities (because music can evoke strong emotions and feelings) and musical preferences (Bailey, 1986; Maslar, 1986; Michel & Chesky, 1995; http://www.musictherapy.org/). Effectiveness The vast majority of studies that regard music therapy for pain managements focus on acute pain, such as dentistry, labor, and postoperative pains. These studies conclusively find it to be effective for reducing a patient’s pain level (Bailey, 1986; Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963; Michel & Chesky, 1995; http://www.musictherapy.org/). In Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague’s study, where they evaluated how music and suggestion contributed to pain, they discovered that music therapy works best for slowly rising pain as opposed to sudden, sharp pain (1963). Music therapy alleviates pain both psychologically and physiologically (Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963). Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague evaluated forty-two Tufts University students, each of whom was provided with headphones and a listening device (1963). The experimental group’s listening devices enabled them to adjust levels of music and white noise, and the control group’s listening devices did not produce any sound, but they were told it emitted an ultrasonic sound. Some members of each group were told that the device would allow Music Therapy 5 them to endure more pain, but others were told nothing. Their fingers were then placed into an ice water bucket and the amount of time that they could tolerate the freezing water was measured. From this study, Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague were able to conclude that although neither the music alone nor just the suggestion that the “ultrasonic” apparatus would work significantly elongated the amount of time of the individual’s tolerance (their p-values were 0.073 and 0.254, respectively), when those two factors were combined, the results improved dramatically, with a p-value of 0.006. In 1981, Locsin performed a post-operative study on twenty-four women who underwent gynecologic or obstetric surgery, testing how music influenced their pain over the first forty-eight hours after their surgery. The experimental group listened to music for fifteen minutes every two hours, after which their pain levels were documented; the control group simply had their degree of pain recorded every two hours. Pain was measured in four different ways. The first method was to utilize the “Overt Pain Reaction Rating Scale (OPRRS),” a scale devised by the experimenters that ranked different observations of pain severity (p. 21). They also measured pulse, blood pressure, and the use of pain medications. The results of their study were that OPRRS, the blood pressure measurements, and the amount of pain medication used all showed marked decreases in pain for the experimental groups for the full forty-eight hours, but that the pulse data only showed differences in the last twenty-four hours. After the experiment, they also questioned the women about their post-operative pain, and those who had taken part in the music therapy recounted less pain. Physiological Causes Music Therapy 6 Both Maslar and Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague attributed the decrease in pain to the fact that it hinders signals in the brainstem that are triggered by pain (1986, 1963). Maslar goes on to explain that this occurs because of Melzack’s Gate Control Theory, which states that the spinal cord is able to control the flow of nerve impulses to the brain, and that music affects the workings of these “gates”. She says: This theory validates the fact that it is the sensory-discriminating capabilities of an individual that will decide the amount, perception, and responses to the pain. Melzack’s Gate Control Theory substantiates using music as a distraction away from the pain stimulus, and gives a foundation on which future research can be based. (p.216) When multiple separate stimuli simultaneously occur, only the strongest enters consciousness (Maslar, 1986). Psychological Causes The most documented psychological reason that music therapy reduces pain is that it simply distracts the patient and directs focus away from him- or herself (Bailey, 1986; Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963; Michel & Chesky, 1995). Furthermore, musical therapy improves mood and reduces stress, tension, and anxiety, all of which contribute to pain (Maslar, 1986). Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague also found that music therapy produces the best results when it is combined with the assurance that it will help relieve the patient’s pain (1963). Observable Effects Music Therapy 7 Although pain is primarily a subjective experience, and thus the measurement of it is also fairly subjective, there are some concrete indicators of pain that can be used to assess its intensity. To begin with, pain elevates pulse and blood pressure, but music therapy can regulate both symptoms (Locsin, 1981). Music therapy also reduces the amount of pain medications that a patient intakes, an obvious sign of pain reduction (Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986). Lastly, those patients who undergo music therapy have shortened recovery periods (Maslar, 1986). Chronic Pain All the research previously discussed has pertained to the treatment of acute pain. Although the existing data leans toward music therapy being effectual for chronic as well as acute pain, there are simply not enough studies to verify if it is in fact a reliable method for treating chronic pain (McCraffrey & Freeman, 2003). In their 2003 inquiry, McCraffrey and Freeman analyzed how music therapy impacted chronic pain, specifically osteoarthritis. Their study lasted for fourteen days and included sixty-six senior citizens, all with osteoarthritis. The experimental group listened to music for twenty minutes a day and the control group just sat quietly for twenty minutes a day. Their results showed that in various ways of comparing the data, those who engaged in music therapy always fared better. Firstly, on any given day, the pain levels of the experimental group were lower after the music therapy than they had been before. Secondly, for each individual day, the experimental group had less pain after listening to the music than the control group did after sitting quietly. Lastly, over the course of the Music Therapy 8 fourteen days, the experimental group experienced an overall decrease of their chronic pain, whereas the control group showed no substantial change. Critique of Studies Although all the aforementioned studies and articles are considered by the author to be legitimate sources of scientific information, there are, as there is with any scientific research, some weaknesses in them. Since pain is a subjective experience, it is hard to measure, and the fact that people have different pain thresholds further complicates the matter. Most of the studies lack concrete physical evidence; they rely solely or primarily on the scientist’s observations and the patient’s reports of pain. In Maslar’s 1986 review of music therapy for pain management, she perceived some additional shortcomings: many experimenters used auditory stimulation instead of music, and those that did use music failed to include in their publications what kind of music was used, preventing replication. She states that using auditory stimulation as opposed to music in a scientific study is understandable because of the need for objectivity (auditory stimulation is easier to keep consistent) and because it prevents responses from being influence by musical taste. Despite these advantages, auditory stimulation is still different from music, and so one could argue that it produces different results and therefore studies using just auditory stimulation are inapplicable to music therapy research. Conclusion Music therapy has been proved to be effective for lessening acute pain (Bailey, 1986; Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963; Michel & Chesky, 1995; http://www.musictherapy.org/). Melzack, Weisz, and Sprague found in their experiments that when an individual listened to music and was told the music would Music Therapy 9 reduce their pain, the individual was able to tolerate the ice water surrounding their fingers longer (1963). Locsin found when post-operative women listened to music, the scientists observed less severe manifestations of pain and more regular blood pressures and pulses (although the pulse only showed a significant difference in the second day) and the women reported less pain when questioned directly (1981). In the reviews by Bailey, Maslar, and Michel and Chesky, music therapy was further documented to be effective. Biologically, music therapy works by inhibiting the nerve impulses conveying pain (Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963). Psychologically, it succeeds in lessening pain by distracting the patient from his or her pain and by positively affecting other factors that contribute to pain, namely mood and stress (Bailey, 1986; Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986; Melzack, Weisz, & Sprague, 1963; Michel & Chesky, 1995). Music therapy clearly demonstrates its functionality for alleviating acute pain in that it quickens recovery, decreases pain medication consumption, and normalizes pulse and blood pressure (Locsin, 1981; Maslar, 1986). In conclusion, music therapy is highly recommended for acute pain management, particularly when pain medication is not sufficient or when conditions prevent pain medication from being utilized. Because it has next to no adverse side effects and the few experiments performed have shown it to be helpful, music therapy is suggested for chronic pain management as well. However, more research needs to be done on music therapy and chronic pain before it becomes a commonplace practice, and it is strongly advocated that more research on this topic be executed. Music Therapy 10 Music Therapy 11 References American Music Therapy Association. (1998). (American Music Therapy Association, Inc.) Retrieved September 2010, from American Music Therapy Association: http://www.musictherapy.org/ Bailey, L. M. (1986). Music Therapy in Pain Management. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management , 1 (1), 25-28. Locsin, R. (1981). The effect of music on the pain of selected post-operative patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 6 (1), 19-25. Maslar, P. (1986). The Effect of Music on the Reduction of Pain: A Review of the Literature. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 13, 215-219. McCaffrey, R. &. (2003). Effect of music on chronic osteoarthritis pain in older people. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 44 (5), 517-524. Melzack, R. W. (1963). Stratagems for Controlling Pain: Contributions of Auditory Stimulation and Suggestion. Experimental Neurology , 8, 239-247. Michel, D. &. (1995). A Survey of Music Therapists Using Music for Pain Relief. The Arts in Psychotherapy , 22 (1), 49-51.