The Syntagmatic Delimitation of Lexical Units

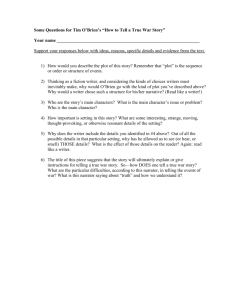

advertisement

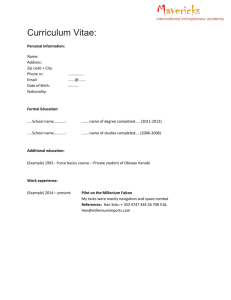

Salahaddin University-Hawler Postgraduate Studies Board (Applied Linguistics/Master) General Linguistics BOOK REVIEW Lexical Semantics D.A. Cruse Reviewer: Wria Ahmed Rashid (M.A Student in Applied Linguistics) Instructor Assist. Prof. Dr. Himdad Abdul-Qahar Muhammd 2011 Introduction: The title of the book is Lexical Semantics by D. A. Cruse. It is first published in 1986 by Cambridge University Press. The book is bulky and consists of twelve long chapters. The writer devotes the first chapter mainly to contextual approach, the relation between meaning and grammar and data collection in semantics. Next, The Syntagmatic Delimitation of Lexical Units is covered; there are talks about Semantic Constituents, indicators, tallies, categorizers, idiom, collocation, and dead metaphor. Chapter three concentrates on the selection and modulation of senses, establishment of senses, and syntactic delimitation. Introducing lexical relations comes next with much explanation on cognitive synonymy, hyponymy, compatibility, incompatibility, and partial relations. When it comes to Lexical Configuration, the writer sheds light on hierarchy, and proportional series. Chapter six and seven covers taxonomies and meronomies respectively. In chapter eight non-branching hierarchies with its types are covered. Then, in three consecutive chapters the writer sheds light on opposites which includes; complementaries and antonyms, directional opposites, antipodal, impartiality, and polarity. The writer ends the book elaborating different aspects in synonymy. Chapter One: A Contextual approach to Lexical Semantics In its introductory part, the book explains that there must be certain basic assumptions concerning meaning. It is assumed that the semantic properties of a lexical item are fully reflected in appropriate aspects of the relations it contrasts with actual and potential contexts. So contextual approach is adopted because of three reasons; first, the relation between a lexical item and extra-linguistic contexts is mediated by the purely linguistic contexts. Second, any aspect of extra linguistic context can be mirrored linguistically and third linguistic context is more easily controlled and manipulated. The writer explains that the information about word’s meaning should be derived from its relations with actual and potential linguistic contexts. In the meaning and Grammar part, the writer states that a clear- cut distinction between meaning and grammar cannot be made, because they are interwoven (grammar serves meaning); he argues that the distinction between the two has a strong intuitive basis. Then he goes on discussing the deviance of grammar and meaning, he gives many examples to clarify different scenarios; among them are: It is too light for me to lift. I have nearly completed. In sentence 1, the deviance disappear by substituting word ‘light’ with ‘heavy’, so the sentence semantically and syntactically sounds well. However, in sentence 2, the syntactic deviance can be treated by adding the word ‘them’ at the end, but semantically it is almost empty. Then the writer suggests that to correct a deviant sentence, we can depend on close set items and open set items. He defines the former as items belong to classes whose membership is virtually constant during the lifetime of an individual speaker, while the latter is defined as those who belong to classes which are subject to a relatively rapid turnover in membership, as new terms are coined and others fall into obsolescence. In the Data of Semantics part, the writer states that for lexical semantics there are two principal sources of primary data, the first one is productive output, spoken or written, of native users of the language. The disadvantage of this source is when it comes to the study of dead languages, as the evidence available to the researchers is a corpus of written utterances. The second source is intuitive semantic judgments by native speakers of linguistic materials of one kind or another. Two important questions arise from these judgments, first what sort of linguistic items should native speakers be asked to pass judgment on? And second is; what sort of judgments should they be asked to make? In the Disciplining Intuitions, the author explains that no empirical science can operate without human intuitive judgment intervening at some point. But at the same time science would be much less advanced than it is if the only available data were intuitive estimates of quantities, and since obtaining straightforward institution is difficult we must ask our informants questions that can be answered reliably and accurately. According to the writer the simplest and the most basic semantic judgments is concerned with the oddity of an utterance produced by a native speaker. For example: - ? This is a club exclusively for married bachelors. - This is a club exclusively for married men. - ? Let’s sit by the stream and have a drink of time. - Let’s sit by the stream and have a drink of tea. On the other hand, the writer explains that an odd sentence is not necessarily meaningless (it is signal for creativeness) It's tea-time for my pet rabbit. It's tea-time for mv pet scorpion. It's tea-time for my pet amoeba. Then the writer says; a very useful intuition for semantic analysis is that of entailment, and it can be used directly, thus, the statement ‘that’s a dog’ entails ‘that’s an animal’. The writer also talks about four logical relations which can be deduced from intuition of entailments, they are: 1. Unilateral entailment: 2. Mutual entailment, or logical equivalence : 3. Contrariety 4. Contradiction In the meaning of a word part, there is a discussion about contextual relations, the writer argues that the meaning of a word is fully reflected in its contextual relations and the meaning of a word is constituted by its contextual relations. He then talks about affinity and classifies them into two kinds: syntagmatic and paradigmatic. Syntagmatic affinity is established by a capacity of a normal association in an utterance for example the relation between ‘dog’ and ‘barked’. Chapter two: The Syntagmatic Delimitation of Lexical Units It its introductory part it mentions that a lexical item can be characterized in three distinct ways; first by its form (graphic and phonological), second by its grammatical function and third by its meaning. In this part the writer also elaborates that the basic syntagmatic lexical units of a sentence will be defined as the smallest parts which satisfy the following two criteria; (i) a lexical unit must be at least one semantic constituent (ii) a lexical unit must be at least one word. In Semantic Constituents part, he explains that any constituent part of a sentence that bears a meaning which combines with the meanings of the other constituents to give the overall meaning of the sentence will be called as a semantic constituent (example, a cat sat on the mat). However, a semantic constituent, which cannot be segmented into more elementary semantic constituents, will be called minimal semantic constituent (the, cat, sat, on, the, mat). The writer introduces a diagnostic test for semantic constituency which is called recurrent semantic contrast. He illustrates it by giving below example: Cat/dog (The----sat on the mat=cat/dog (We bought a -----) In Semantic Constituents which fail the test part, the writer clarifies that in large number of items semantic constituent test can be applied appropriately; however, there are certain peripheral types of semantic constituent which cannot be directly subjected to the test due to their occurrence in association with other elements like cran- of cranberry. It is also the case in the collocational uniqueness. Furthermore, the writer talks about the Discontinuous Semantic Constituent for example in those books, the s does not signal the plurality alone, it is by the help of those. In Indicators, tallies, and categorizers part, the writer explains that when an element does not carry any meaning at all can be called Semantic tally, and its partner element which indicates a general category is called semantic categorizers. He also talks about semantic indicators as elements which fall short of being constituents but has a semantic function related to the meaning of the same form. In word part, he talks about two characteristics of words; first a word is the smallest element of a sentence which has positional mobility. Second, words are typically the largest units which resist ‘interruption’. New materials cannot be inserted between its constituent parts. Then in Idiom part, the writer defines idiom as an expression whose meaning cannot be inferred from the meanings of its parts. Idiomatic expressions must be distinguished from non-idiomatic one. Based on the notion of semantic constituent, an idiom should be lexically complex and it should be a single minimal semantic constituent. Any expression which is divisible into semantic constituents is called semantically transparent. In idioms and Collocation part, colocations is defined as terms that refer to sequences of lexical items which habitually co-occur, but which are nonetheless fully transparent in the sense that each lexical consistent is also a semantic constituent. Examples are torrential rain, fine weather, etc. Unlike idioms, most colocations are lexically not complex, and when they are they are called bound collocations. In the Idiom and dead metaphor part, the writer explains that a metaphor induces the hearer to view thing as being like something else by applying to the former linguistic expressions which are more normally employed in references to the latter. Consider the following: They tried to sweeten the pill. They tried to sugar the medicine. First sentence contains a dead metaphor and it is substituted by near synonym. Dear metaphors are the ones who lose their characteristic flavor, their capacity to surprise, and hearers encode the metaphorical meaning as one of the standard senses of the expression due to their frequent use. Chapter three: The Paradigmatic and Syntactic Delimitation of lexical units In the Introductory part, the writer makes distinction between lexical units and lexemes. He states that lexical units are those form- meaning complexes with relatively stable and discrete semantic properties which stand in meaning relation such as hyponymy (dog, animal). Lexemes on the other hand, are the items listed in the lexicon or ‘ideal dictionary’ of a language. In the Selection and modulation of senses part the writer illustrates his points in the below two sentences: Sue is visiting her cousin We finally reached the bank In the first example, although the word ‘cousin’ does not refer to ‘male cousin’ or ‘female cousin’, the sentence can function as a satisfactory communication due to its generality in meaning. However, in the second example, the word ‘bank’ can be interpreted in more than one way (margin of river or an establishment for the custody of money). So the word ‘cousin’ is general, but the word ‘bank’ is ambiguous. The writer also gives thorough explanation about direct and indirect ambiguity and he introduces some criteria for each. Then he concentrates on some difficult cases related to ambiguity. In Non-Lexical sources of ambiguity part, he states that not all sentence ambiguity originates in lexical ambiguity, and tests applied are not capable in discriminating between lexical and non-lexical varieties. Thus he introduces some other types of ambiguity such as: - Pure syntactic ambiguity (old men and women) - Quasi-syntactic ambiguity (A red pencil) (painted red or writes red) - Lexico-syntactic ambiguity (I saw the door open) - Pure lexical ambiguity (He reached the bank) In Establishment of senses part, the writer explains that a lexical form may be associated with an unlimited number of possible senses, but they are not with equal status. However, each lexical term has at least one well-utilized sense. The writer illustrates that since the establishment is represented differently in the mind’s lexicon, it is better to distinguish two types of contextual selection. First is passive selection when the selection is acts as a kind of filter as the sense is preestablished. The second one is productive selection when the context acts as a stimulus for a productive process. Then he says the number of fully established senses is finite at any one time, and it might be advantageous to limit the class of lexical units to these. Still the writer does not hide that there is a problem and it is related to different members of language communities therefore, he believes such limit will result in a distorted picture of word meaning. He then talks about sense-spectra and defines it a certain aspects of word meaning that are difficult to reconcile with the view of well-establishment senses and somehow awkward. For example in the case of dialect continuum, where mutual intelligibly is somehow lost. In syntactic delimitation part the writer argues that two occurrences of lexical form which represents two different grammatical elements should be regarded as lexically distinct. In lexemes part the writer states that one of the remarkable feature of language is making infinite use of finite resources. The writer also gives a short account about the derivational and inflectional affixes. He then, clarifies that some lexical units are basic and others are central for making lexemes and thus he divides them into primary and secondary. Chapter 4: Introducing lexical Relations As the writer explains, sense relations are of two fundamental types; paradigmatic and syntagmatic. They have their own distinctive significance. Paradigmatic relations represent systems of choice a speaker faces when encoding his message. On the other hand, syntagmatic lexical meaning serve discourse cohesion, adding necessary information redundancy to the message, and at the same time controlling the semantic contribution of individual utterance through disambiguation. In congruence part, the writer introduces four basic classes for dealing with lexical relations; they are; 1. Identity (when class A and class B have the same members) 2. Inclusion (When class B is wholly included in class A) 3. Overlap (Class A and class B have members in common but each has members not found in the other) 4. Disjunction: (When class A and class B have no members in common) In Cognitive synonymy part, the writer explains that X and Y are synonym if they are syntactically identical and any grammatical declarative sentence S containing X has equivalent truth conditions to another sentence S1. One example is in the case of ‘fiddle’ and ‘violin’. Then, hyponymy is defined as the lexical relation, corresponding to the inclusion of one class in another. For example (dog, animal) Compatibility is defined as the lexical relations which corresponds to overlap between classes. It has two important characteristics; first, there are no systematic entailments between sentences differing only in respect of compatibles in parallel syntactic positions. Second it guarantees a genuine relationship of sense; a pair of compatibles must have a common superordinate. The writer defines incompatibility as the sense relations which is analogues to the relation between classes with no members in common (it is a cat entails it is not a dog) Partial relations are described as relations which hold between lexical items whose syntactic distributions only partially coincide. In the remaining parts of this chapter, the writer talks about quasi-relationship, Pseudo-relations, and Pararelations. Chapter 5: Lexical Configuration This chapter deals with two complex types of lexical configuration; they are hierarchies and proportional series. A hierarchy is a set of elements related to one another in a characteristic way. Two structural types of hierarchy may be distinguished, those which branch and those which due to the nature of their constitutive relations are not capable of branching. Branching and Non- branching hierarchy can be further classified according to the writer. The simplest Proportional series consists of a single cell which has four elements. The relation between the elements must be such that from any three of the elements the fourth can be uniquely determined. Mere stallion Ewe ram But the writer explains that it is not always the case, consider the below: Apple fruit Dog animal Chapter 6: Taxonomies The writer regards taxonomy as a sub-species of hyponymy. It is characterized in terms of a relation of dominance and a principle of differentiation which were more intimately related. Recognizing taxonomy is one thing; describing its essential nature is another and more difficult task. A strong correlation can be observed between taxonomies and what are called natural kind terms. They show proper names in the way that they refer. The referents would not lose their entitlements to current labels whatever changes in our perception of their nature were to come about. The writer brings an imaginary example and says: Suppose that all cats were discovered one day to be not animals at all but highly sophisticated self- replicating robots, introduced to earth millions of years ago by visitors from outside our galaxy. Would this discovery lead us to explain (Ah, cats do not exist). The writer clarifies some characteristics of natural taxonomies, one of them is that they typically have no more than five levels, and frequently have fewer (unique beginner, life-form, generic, specific, and varietal). According to the writer the specific of an expression can be included in two ways; first by adding syntagmatic modifiers, the book, the red book, the tattered red book, etc. second by replacing one or more lexical items in an expression by hyponyms (including taxonomies), It’s an animal, it’s a monkey, it’s a colobus. Chapter 7: Meronomies It is one of the major types of branching lexical hierarchy. It is part whole type. For example (palm+ finger= hand). The writer here also mentions some characteristics of parts such as topological stability and spatial continuity, having their boundaries motivated and their definite functions is relative to their wholes, ex. Eye for seeing, Brake for stopping, etc. In the part tilted Aspects of transitivity, the writer refers to two causes of failure of transitivity of the part whole relation; the first involves the notion of functional domain, consider the below example: The house has a door. The door has a handle. ? The house has a handle. The second failure is caused by a special type of part which is called attachment: A hand is attached to an arm. (Attached to some larger entity, it is normal) ? The palm is attached to a hand (it is integral part of the entity, it is odd) There are various dimensions in the whole part relations: 1. Concreteness: bodies, trees, and cars are all concrete but one may also speak of non-concrete entities such as events, actions and states. 2. Degree of differentiations amongst parts: the parts of body, the car are highly differentiated. 3. Structural integration: The numbers of a team are more integrated than books in a library but are less so than parts of a body. 4. Items in a relationship are count nouns or mass nouns. Chapter 8: Non-branching hierarchies The writer classifies non-branching into two sub types: first there are those which are closely bound up with branching hierarchies, and they can be regarded as secondary derivations from them. Second, there is quite a large family of independent non-branching hierarchies not derived from or connected in any way with branching hierarchies. Non-branching can mainly be applied on sentences which are not like human bodies, when well-formed, they do not all have to contain the same inventory of parts. Some are more compels than others and consists of a larger number of parts. Still the multiplication of parts is not haphazard, but it is subject to certain constraints, in the absence of which it would not be possible to label the parts. The writer explains that the simplest way of deriving a non-branching hierarchy from branching one is to provide labels for the levels. For example; sentence level, clause level, phrase level, word level, and morpheme level. Chapter 9: Complementaries and antonyms The writer explains that of all the varieties of opposites, complementarity is perhaps the simplest conceptually. They divide some conceptual domain into two mutually exclusive compartments so that what does not fall into one of the compartments must necessarily fall into the other. There is no neutral ground. For example true, false, or deal, alive. Complementaries can be recognized by the fact that if we assert one term, we implicitly deny the other. For example, John is not dead entails and is entailed by John is alive. According to the writer Complementaries are either verbs or adjectives. An interesting feature of verbal complemnatries is that the domain within which the complementarity operates is often expressible by a single lexical item, for example; obey and disobey. The write also talks gives short account of four types of opposites, they are; reversives (born, die), interactives (stimulus-response), satisfactives (try, succeed), and counteractives (attack, defend). Antonymous is exemplified by such pairs as long/short, fast/slow, easy/difficult. They share the following characteristics: 1. They are fully gradable 2. Members of a pair denote degrees of some variable property such as length, speed, accuracy, etc. 3. The members of a pair move, as it were in opposite directions along the scale representing degrees of relevance. In this chapter the writer also briefly discusses Implicit Superlatives such as in scale of size (tiny/huge, enormous/minute) and stative verbs (like/dislike) Chapter 10: Directional opposites The writer states that direction defines a potential path for a body moving in a straight line, a pair of lexical items denoting opposite directions indicate potential paths. Although there are no lexical pairs denoting pure contrary motion, there are pairs which in their most basic senses denote pure opposite directions. They are all adverbs or prepositions. Then he brings examples of north, south, up, down, forwards, backwards and their uses in this regard. Antipodal comes next in which one term represents an extreme in one direction along some salient axis, while the other term denotes the corresponding extreme in the other direction. For example if we go up as far as we can while remaining within the confines of some spatial entity we reach its top, and in the other direction the lower limit is the bottom. As the writer indicates, reversives are those pairs of verbs which denote motion or change in opposite directions. Examples are rise/fall, ascend/descend. Syntactically, the most elementary type of reversive opposites are intransitive verbs whose grammatical subjects denote entities which undergo changes of state: appear/disappear, enter/leave. Converses are defined as an important class of opposites consists of those pairs which express a relationship between two entities by specifying the direction of one relative to the other along some axis. Examples are servant/master, ancestor/decedent. Chapter 11: General questions The writer sheds light on Impartiality and distinguishes two modes of it; they are strong partiality (appears only in connection with gradable opposites, i.e. antonyms and it is not restricted to any particular sentence type) and weak partiality (occurs only in yes-no questions, they appear typically with non-gradable Complementaries such as dead/alive). Example of strong partiality: How thick is it? Mine is thicker than yours. Examples of weak partiality Is he married? (or not?) Is he single/ (or not?) In polarity part, the writer explains that many opposite pairs are asymmetrical in that one member bears a negative affix, while the other has no corresponding formal mark, example; happy/unhappy, like/dislike, etc. However, in an example like, increase/decrease there is a formal mark which can be spoken about as positive and negative terms of the opposition. The writer believes that the results of 'morphological experiments' reinforce the above mentioned intuitions. He also links the positive terms with strong partiality. According to the writer opposition is a special case of incompatibility. For example long and short are incompatible, since nothing can be at once long and short. He also talks about a lexical gap, for example when a word has opposite but there is no such word to express the opposite, for instance in the word devout. Chapter 12: Synonymy In this long chapter, the writer starts with two robust semantic intuitions. The first is that certain pairs or groups of lexical items bear a special sort of semantic resemblance to one another. The second intuition is that some pairs of synonyms are 'more synonymous’ than other pairs: settee and sofa are more synonymous than die and kick the bucket. These two semantic intuition points to something like a scale of synonymity. The writer further illustrates that since there is no neat way of characterizing synonyms, we should approach the problem in two ways: first in terms of necessary resemblance and permissible difference and second contextually by means of diagnostic frames. The writer talks about absolute synonym (identical synonym) and partial synonym thoroughly. He also gives a short account of dialectal synonym which occurs due to geographical variety and has minor significance, such as fall/autumn, lift/elevator, glen/valley. Conclusion The book covers wide range of areas in semantics and lexical relations and is quite beneficial to students. It is enriched with larger number of examples necessary for easy understanding. It approaches the subject in detail starting with simplest discussion and then making it more complex and thought-provoking which encourages critical thinking. On the other hand, however, the language of the book is difficult, and much background in semantics is needed to properly understand every aspect mentioned by the writer. So for readers to follow the items and arguments in the book, they must be equipped with sufficient basic, but detailed information regarding concepts of meaning, lexical items, and other related terminologies. Perhaps the book is most useful for well-advanced students in the field of semantics. Moreover, since the book is written many years ago, it is recommended that its content and subjects tackled, be compared with other recently well-written books because the writer uses flexible approach in conveying his opinion on the subjects leaving the door wide open to disagreement on his statements. It is left to mention that, personally I have gained some information regarding meaning based on intuition, data collection in semantics, dead metaphor, semantic constituents and establishment of senses.