A History of the Clan System

advertisement

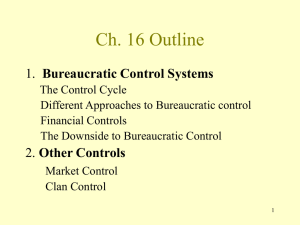

A History of the Clan System The origin of the Scottish Clans is a subject of some controversy but it is generally acknowledged that the Highland clans were in existence at least during the early 1100s. The Norman conquest of England in 1066 and the subsequent subjugation of King Malcolm Canmore (Malcolm I) were significant events in the developing history of the Scottish clans. The introduction of feudalism produced a total change of English culture and major changes in Scotland within three generations. “English” and “Scots” languages merged and were often replaced by the language of the Normans. In Gaelic, clann means children, and, by extension, descendants. The head of each clan was often a “king,” which over the years evolved into “chief.” Members of the clan did not necessarily bear the same name. At first, only the chief and his family used fixed surnames to indicate their descent from the founder of the clan. Around the 17th century, the use of surnames among all clans in the Highlands became the norm. In the early history of Scotland’s clans, to avoid corruption, the king was not permitted to own property. The clan provided for all his needs in return for his wise leadership. Succession was hereditary within a family, with each clan electing a new king. It was a unique system, whereby the lowest member shared a common bond with the king, totally different from feudalism, in which each rank in society owed their lord everything. As the clan system developed, “broken” men --men without a connection to any clan--were allowed to join. Sometimes, tenants of clan lands who came from outside the clan became members after three generations of tenancy. In spite of that affiliation, however, these tenants were still not considered blood members of the clan. In yet another variation of membership, an entire clan or “sept” (a branch of a clan) could be accepted into another clan after losing the last of its chiefs or its territory. Smaller clans sometime swore fealty to a larger clan for safety. Traditionally, the men of the clan were called together by a fiery cross (crois taraidh), which was made from two pieces of burned, or burning, wood. A relay of runners tied the pieces of wood together with a rag soaked in blood and carried the cross from glen to glen. Generally speaking, the men in most clans fought and hunted, while the women and older children did the work at home. A steady source of income for some clans was “blackmeal,” or protection money, which the Lowlanders or other neighbors paid to buy off the raiders. In spite of his often humble surroundings, a clan chief tended to create the kind of pageantry usually associated with royalty. Whenever he traveled, his huge entourage followed. First, were his henchmen or personal bodyguard. Next, came the bard (Seanachaidh). It was the bard’s duty to record the chief’s heroic deeds, including those of the clan and the chief’s forebears. Following the bard was he piper. The piper ’s position was hereditary one, passing father to son. The bard and the piper often followed the chief into battle, “the former that he might witness with his own eyes his leader ’s acts of valour, and the latter to inspire the Clan to greater heroism by his playing,” wrote Scottish historian Fitzroy MacLean. Next up was the chief’s spokesman (Bladaire), who functioned as a king of protocol officer. The spokesman’s role was to issue proclamations for the chief or argue the chief’s position on a dispute. Finally, bringing up the rear of the company was a ghillie, or two, who carried the chief’s broadsword and shield (targe). The last rites given to a Highland clan chief were no less renowned for spectacle than his entourage. Regardless of the distance, custom dictated that the chief had to be buried with his fathers. The chief’s corpse was carried feet first, with the piper ’s place at the head. Tightly furled in front was the clan standard. Following behind were the Clansmen with drawn swords. Attending every funeral was the piper, whose music honored the dead as well as inspired the bearers on the march. The women of the clan followed the funeral march as far as the first brook (burn). At that point, they presented a cup of wine, which symbolized a prayer for the departed. Because the distances to the burial ground could be quite lengthy, the custom of wakes began among the Gaelic-speaking descendants of both the Scots and the Irish. Although they now have a reputation as being somewhat rowdy, wakes evolved gradually from the quiet, reverential vigils of Roman Catholicism. Inclement weather was no obstacle to a proper and ceremonious burial for a Clan Chief. In fact, if anything, it spurred the burial party to even greater pride in their duty as the procession chanted: “Blessed be the corpse the rain rains on.”