Gladiatorial Games

advertisement

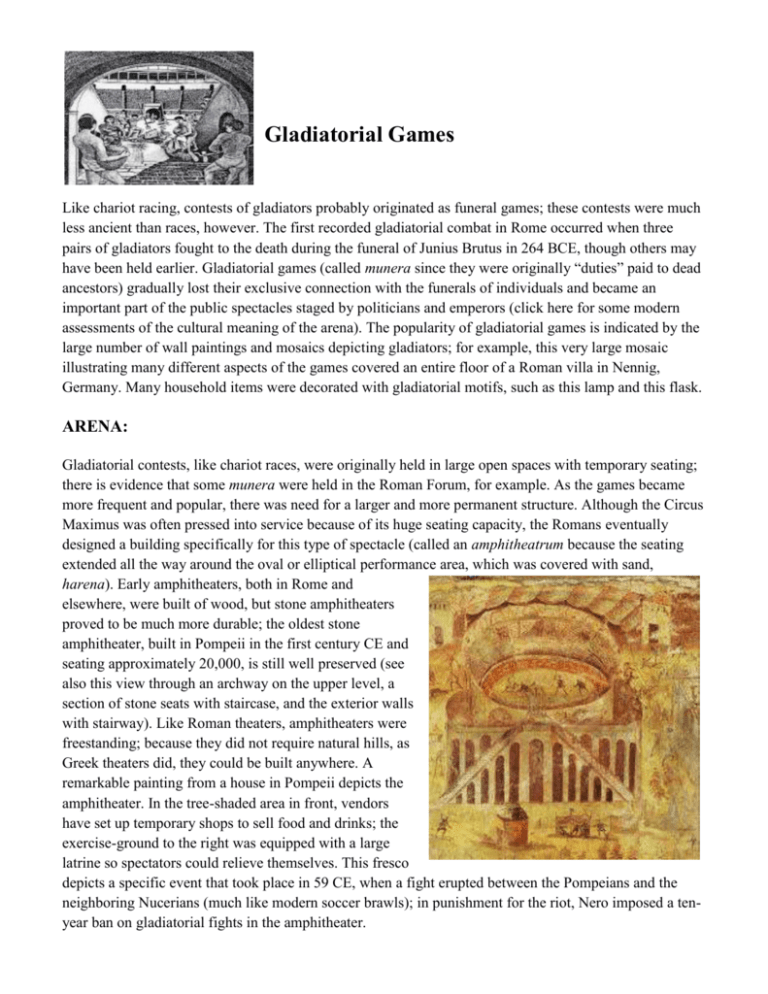

Gladiatorial Games Like chariot racing, contests of gladiators probably originated as funeral games; these contests were much less ancient than races, however. The first recorded gladiatorial combat in Rome occurred when three pairs of gladiators fought to the death during the funeral of Junius Brutus in 264 BCE, though others may have been held earlier. Gladiatorial games (called munera since they were originally “duties” paid to dead ancestors) gradually lost their exclusive connection with the funerals of individuals and became an important part of the public spectacles staged by politicians and emperors (click here for some modern assessments of the cultural meaning of the arena). The popularity of gladiatorial games is indicated by the large number of wall paintings and mosaics depicting gladiators; for example, this very large mosaic illustrating many different aspects of the games covered an entire floor of a Roman villa in Nennig, Germany. Many household items were decorated with gladiatorial motifs, such as this lamp and this flask. ARENA: Gladiatorial contests, like chariot races, were originally held in large open spaces with temporary seating; there is evidence that some munera were held in the Roman Forum, for example. As the games became more frequent and popular, there was need for a larger and more permanent structure. Although the Circus Maximus was often pressed into service because of its huge seating capacity, the Romans eventually designed a building specifically for this type of spectacle (called an amphitheatrum because the seating extended all the way around the oval or elliptical performance area, which was covered with sand, harena). Early amphitheaters, both in Rome and elsewhere, were built of wood, but stone amphitheaters proved to be much more durable; the oldest stone amphitheater, built in Pompeii in the first century CE and seating approximately 20,000, is still well preserved (see also this view through an archway on the upper level, a section of stone seats with staircase, and the exterior walls with stairway). Like Roman theaters, amphitheaters were freestanding; because they did not require natural hills, as Greek theaters did, they could be built anywhere. A remarkable painting from a house in Pompeii depicts the amphitheater. In the tree-shaded area in front, vendors have set up temporary shops to sell food and drinks; the exercise-ground to the right was equipped with a large latrine so spectators could relieve themselves. This fresco depicts a specific event that took place in 59 CE, when a fight erupted between the Pompeians and the neighboring Nucerians (much like modern soccer brawls); in punishment for the riot, Nero imposed a tenyear ban on gladiatorial fights in the amphitheater. Colosseum: The reconstruction drawing at the top of this page depicts the grandest of all Roman amphitheaters, known in antiquity as the Flavian Amphitheater because it was built by the emperors of the gens Flavia, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, and later called the Colosseum, either because of its size of because of the colossal statue of Nero which stood in the vicinity. The inaugural games were held in 80 CE, though construction continued for some time after that. The exterior walls were four stories high, and the first three stories were adorned with half-columns illustrating the three classic architectural styles (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian). Only a small part of the full structure survives (not because it collapsed, though it was damaged by several earthquakes, but because later Italians used the building as a quarry for centuries, stealing the stones to build St. Peter's and many palaces). What remains of the Colosseum today gives no idea of this amphitheater’s lavish decorations, such as colorfully painted statues, decorative marble, and painted stucco. This model demonstrates the intact structure, and this cutaway section shows details of the construction, as does this labeled drawing. Looking down at the interior of the Colosseum from the top story gives some sense of its size; estimates of seating capacity vary from 40-60,000, with 50,000 most likely. Because the floor of the Colosseum has not survived, we can see the maze of underground structures, corridors, ramps, animal pens (this image from the amphitheater in Pozzuoli shows what the pens in the Colosseum were like), and rooms for prisoners. This view of amphitheater at Capu a illustrates what the floor of the Colosseum would have looked like without the wooden coverings and layer of sand; we can clearly see the rims which held the wooden trapdoors through which animals and men would “magically” appear and which could be used to produce other special effects. When the trapdoors were closed, this subterranean area must have been very dark and frightening, echoing with the roaring of caged animals and the cries of prisoners awaiting execution in the arena (see, for example, this image from Pozzuoli). The top story of the Colosseum was equipped with posts to which were attached a huge awning that would shield the spectators from the hot sun; this image shows the post holders for this awning. Seating in the amphitheater was arranged by rank, with a special box for the emperor and his family and ring-side seats for senators. Those who had the least political clout, foreigners and women, relegated to the topmost rows. GLADIATORS: Status: Gladiators (named after the Roman sword called the gladius) were mostly unfree individuals (condemned criminals, prisoners of war, slaves). Some gladiators were volunteers (mostly freedmen or very low classes of freeborn men) who chose to take on the status of a slave for the monetary rewards or the fame and excitement. Anyone who became a gladiator was automatically infamis, beneath the law and by definition not a respectable citizen. A small number of upper-class men did compete in the arena (though this was explicitly prohibited by law), but they did not live with the other gladiators and constituted a special, esoteric form of entertainment (as did the extremely rare women who competed in the arena; see some Latin passages referring to female gladiators). All gladiators swore a solemn oath (sacramentum gladiatorium), similar to that sworn by the legionary but much more dire: “I will endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword”. Trained gladiators had the possibility of surviving and even thriving. Some gladiators did not fight more than two or three times a year, and the best of them became popular heroes (appearing often on graffiti, for example: “Celadus the Thraex is the heart-throb of the girls”). Skilled fighters might win a good deal of money and the wooden sword (rudis) that symbolized their freedom. Freed gladiators could continue to fight for money, but they often became trainers in the gladiatorial schools or free-lance bodyguards for the wealthy. Types of Gladiators: There were many categories of gladiators, who were distinguished by the kind of armor they wore, the weapons they used, and their style of fighting. Most gladiators stayed in one category, and matches usually involved two different categories of gladiator. The following examples will illustrate some of the different types of gladiators which modern scholars have identified: Eques (“horseman”): The Eques (plural, equites) usually fought against another gladiator of the same type. They probably began their matches on horseback, but they ended in hand-to-hand combat. These were the only gladiators who wore regular tunics rather than any type of body armor (see modern mannequin), though they wore bronze helmets with two feathers and padded shin-protectors; they carried round shields and often fought with long swords. Hoplomachus (“heavy-weapons fighter”): The Hoplomachus, named after the Greek Hoplite warrior, fought with a long spear as well as a short sword or dagger; he wore a visored helmet with crest and long greaves over both legs to protect them since he carried only a small shield, usually round (see original and replica). In this terracotta relief, a Hoplomachus battles a Thraex, who is attempting to reach over his shield and stab him. A late Republican funeral monument depicts a Thraex fighting against a kneeling Hoplomachus, though both gladiators wear early types of crested helmets without visors. Murmillo (“fish”): The Murmillo, named for a Greek saltwater fish, wore a large visored helmet with a high crest; these helmets became increasingly enhanced with relief decorations, as for example the head of Hercules (see also replica), military trophies (see front and side of replica), and the Gorgon, Mars Ultor, and decorative vessels (see replica). The Murmillo was protected by a large, slightly curved, rectangular shield (see replica), so he needed only one short shin-guard (ocrea) to protect his left leg (side view; replica). He fought with a short stabbing sword (gladius). The wreaths on a tombstone from Ephesus indicate that this Murmillo won many combats. In another relief from Ephesus, the Murmillo Asteropaios, on the left, is attempting to stab the Thraex Drakon; both gladiators have lost their shields and are fighting in a “clinch.” Provocator (“attacker”): The Provocator was the most heavily armed gladiator; he was the only gladiator who wore a pectoral covering the vulnerable upper chest. He also wore a padded armprotector and one greave on his left leg; he carried a large rectangular shield and stabbing sword. His large, distinctive visored helmet had no crest and extended over his shoulders (see also replica). The extent of his armor made the Provocator slower and less agile than other gladiators, which may explain why he tended to be paired with another gladiator of the same type in combat. Retiarius (“netman”): The Retiarius was the quickest and most mobile of gladiators; as the only type of gladiator who wore no helmet, he had much more range of vision than his opponents. However, since he wore practically no defensive armor, he was also more vulnerable to serious wounds; his only body protection was a padded arm-protector (manica) on his left arm often topped with a high metal shoulder protector (galerus), also shown in this replica. His weapons were a large net with which he attempted to entangle his opponent, a long trident, and a small dagger (see also replica). The Retiarius in this relief advances on a Secutor who has lost his shield (which is held by the referee). However, looking at the Retiarius in this mosaic, one has to ask, “Why is this man smiling?” because the Secutor appears about to stab him, while the kneeling position of this Retiarius indicates that he has surrendered to the Secutor who stands menacingly above him. Secutor (“pursuer”): The Secutor was typically paired with a Retiarius. His egg-shaped helmet with round eye-holes had no crest or reliefs to snag on the net of the Retiarius but also gave him little range of vision. He wore a short shin protector (ocrea) on one leg and an arm protector; he carried a large rectangular shield and stabbing sword. The wreaths on this tombstone of a Secutor indicate his many victories, while an exultant Secutor named Improbus prepares to dispatch a fallen Retiarius in this relief. Thraex (“Thracian”): The Thraex gladiator was loosely based on the Thracians, former enemies of Rome. His most distinctive feature was his weapon, a short sword (sica) whose blade was either curved or kinked. His visored helmet with wide brim resembled that of a Murmillo except that it was topped with the head of a griffin (see replica). Because the Thraex carried a short rectangular shield, he wore an arm-protector and long shin protectors (ocreae) on both legs (these are decorated with theatrical masks and an eagle vs. snake motif; see also replica). The victorious gladiator in this mosaic is a Thraex, while this Thraex holds up an index finger to signal surrender. A tombstone from Antalya and one from Akhisar in Turkey provide good illustrations of this type of gladiator, In addition, the Bestiarius (“animal-fighter”) was a special type of gladiator trained to handle and fight all sorts of animals. The bestiarii were the lowest ranking gladiators; they did not become as popular or individually well known as other types of gladiators. Although this relief depicts bestiarii wearing armor, most depictions show them without armor, equipped with whips or spears, wearing cloth or leather garments and leggings. Training: The manager of a gladiatorial troupe was called a lanista; he provided lengthy and demanding training in schools (ludi) especially designed for this purpose and usually located near the great amphitheaters. Pompeii, for example, had both a small training area surrounded by gladiatorial barracks near the theater, while there was a large exercise-ground (palaestra) right next to the amphitheater. During the imperial period all the gladiatorial schools in Rome were under the direct control of the emperor. The largest of these schools, the Ludus Magnus, was located next to the Colosseum; it included a practice amphitheater whose partially excavated ruins can be seen today. A DAY AT THE ARENA: Gladiatorial games began with an elaborate procession that included the combatants and was led by the sponsor of the games, the editor; in Rome during the imperial period, this usually was the emperor, and in the provinces it was a high-ranking magistrate. The parade and subsequent events were often accompanied by music; the mosaic at right depicts a water organ and the curved horn (cornu). The morning's events might begin with mock fights such as this contest. These would be followed by animal displays, sometimes featuring trained animals that performed tricks, but more often staged as hunts (venationes) in which increasingly exotic animals were pitted against each other or hunted and killed by bestiarii (click here for more information about venationes). The lunch break was devoted to executions of criminals who had committed particularly heinous crimes— murder, arson, sacrilege (the Christians, for example, were considered to be guilty of sacrilege and treason, because they refused to participate in rites of the state religion or to acknowledge the divinity of the emperor). The public nature of the execution made it degrading as well as painful and was intended to serve as a deterrent to others. One form of execution in the arena was damnatio ad bestias, in which the condemned were cast into the arena with violent animals or were made to participate in “dramatic” reenactments of mythological tales in which the “stars” really died (as for example the myth of Dirce, killed by being tied to a bull). Criminals could also be forced to fight in the arena with no previous training; in such bouts death was a foregone conclusion, since the “victor” had to face further opponents until he died (such combatants were not, of course, professional gladiators). In extraordinary circumstances, criminals might be forced to stage an elaborate naval battle (naumachia). Although these were usually fought on lakes, some scholars think they might also have been staged in the Colosseum, as shown in this modern drawing. In the afternoon came the high point of the games—individual gladiatorial combats. These were usually matches between gladiators with different types of armor and fighting styles, supervised by a referee carrying a long staff (summa rudis). Although it is popularly believed that these bouts began with the gladiators saying “Those who are about to die salute you,” the only evidence for this phrase is only found in the description of a naumachia staged by Claudius using condemned criminals, where the men supposedly said “Ave, imperator; morituri te salutant” (Suetonius, Claudius 21.6). This was certainly not a typical gladiatorial combat and cannot be used as evidence for customary practice. There were, however, many rituals in the arena. When a gladiator had been wounded and wished to concede defeat, he would hold up an index finger, as clearly depicted on the Colchester vase and on the mosaic below. At this point the crowd would indicate with gestures whether they wished the defeated gladiator to be killed or spared. The popular belief is that “thumbs down” meant kill and “thumbs up” meant spare. In any case, the sponsor of the games decided whether or not to give the defeated gladiator a reprieve (missio). If the gladiator was to be killed, he was expected to accept the final blow in a ritualized fashion, without crying out or flinching. Some scholars believe there was also a ritual for removing the bodies of dead gladiators, with a man Hades hitting the body with a hammer to make sure he was really dead and then a slave dragging the body with a hook through a gate.