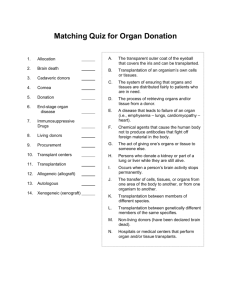

Organs Without Borders?

advertisement