File - Greg Whitehurst`s Online Composition Portfolio

advertisement

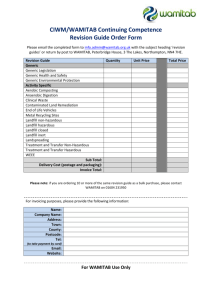

Whitehurst 1 Greg Whitehurst Dr. Guenzel ENC 1102, Sec #2 26 March 2013 Research Dossier: Generic vs. Brand-Name Psychoactive Medications Dossier Introduction In the medical field, the choice between generic and brand-name psychoactive drugs, both by prescribing doctors and by their patients, is fueled by the question of whether or not they truly are the same. Researching this topic has led me to find that this has been a highly unresolved issue with compelling evidence on both sides, and that the word “same” in this context is subject to debate itself. The generic drug market began in the 1920’s with generic aspirin, but regulations on the efficacy of generic drugs were loose until 1962 with the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The legislation was an answer to a tragic occurrence of birth defects across Europe due to a generic sedative on the market, and the FDA required that all generic drugs go through human trials similar to the process for brand-name versions. Since then, regulations have been softened, with the FDA only needing proof that the generic drug is chemically the same, or the bioequivalent of the brand-name before it can be introduced to the market. This raises many concerns, including whether the evaluation process of generic drugs is rigorous enough or if they even have the same effects on patients. Although it is important that the generic medications truly are bioequivalent, the psychology of the individual taking the drug must be taken into account, especially in the case of drugs that alter physical brain function. Because there are no longer tests for generic drug efficacy, this is where research is needed: to understand if generic drugs are as effective and safe as brand-name drugs regardless of their bioequivalency. I believe this is a very important topic to be understood. It is estimated that up to 50% of the United States population will suffer from at least one psychiatric disorder in their lifetime, and at least half of those individuals will seek treatment. Many individuals are prescribed psychoactive drugs for issues such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, or even less serious problems such as trouble sleeping. The psychiatrists who choose to prescribe one version of the drug or the other have a responsibility to know any potential harm generics might cause, and anyone currently taking a prescription psychoactive drug should be informed on any potential differences. These two groups of people would mainly benefit from this research. After researching the topic at great length, it seems there are three sides to the issue although they are not entirely distinct. Surveys and studies show that a significant percentage of people do not expect generic drugs to be as effective as the brand-name versions, and Whitehurst 2 interestingly this belief seems to actually reduce the effectiveness of the medication when patients are switched from one to the other. This is known as the nocebo effect, and it is part of the argument that since the difference stems from patients’ beliefs, that doctors simply need to fully educate their patients about how generic drugs are no different than the brand-names. The sources listed that apply to this argument are Gaudiano and Miller’s study of bipolar patients (2007) and Roman’s 2009 survey given to patients on antipsychotics; all of the sources referenced in this paragraph can be found in the annotated bibliography at the end of this paper. A second viewpoint is based off of case studies that show severe relapses in patients who are switched to generics, and this viewpoint claims that more trials and research are needed for generic drugs because of the serious complications that sometimes occur. This view also gives importance to manufacturing differences, and the sources for it are a meta-analysis by Borgheini (2003), case studies reviewed by Margolese (2010), and a magazine article by Dunckley (2012). A final argument lies somewhere in the middle, with the idea that because generics do sometimes cause problems, this can be solved by evaluating any potential switch to generics on a case by case basis. The sources related to this argument are journal-published studies by Bobo (2010) and Howland (2010). I will be looking at all three sides of the issue; I hope to provide relevant information for doctors and patients to make well-informed decisions when choosing brandname or generic medication. Research Map Progress My original idea was based off Daniel Ariely’s research showing that painkillers are less effective when people are told they are discounted versions of the normal painkillers. This study was referenced in the non-fiction book Cheap by Ellen Ruppell Shell, and my research goal became: How do generic or brand-name psychoactive medications affect people differently based on their perceptions of the differing costs? This became more complex as I discovered that most research until now has only been able look at the differences by observing individuals who have switched from one to the other, and most do not specifically look at cost perceptions. Thus, I had to expand my research on how the perceptions and expectations of individuals influence efficacy. The thesis for my research is that brand-name medications have a higher efficacy than generic medications in treatment, but this is only because of the perceptions of the patients as opposed to the manufacturing of the drugs. The research thus far has led me to believe that this thesis is accurate, although my research focused more on the effects on the patients rather than the manufacturing process. As far as I can tell, no studies trace back a generic drug to where and how it was manufactured when there is a problem with a patient. This research question could be easily answered if there were many controlled studies that used a sample of individuals who were given a brand-name drug and another sample who Whitehurst 3 were given a generic. However, these studies are extremely rare. I was able to find many sources from scholarly journals, the internet, magazines, and newspapers. I do plan, though, to do a survey myself asking individuals what their attitudes on generic drugs are. I have had four exams and two quizzes in the past week, so I have not had time yet to perform this survey. It will, though, give me a field research source that will hopefully reinforce current studies that show a significant percentage of people feel like generics are less effective than brand-names. Key Terms Generic Drugs Brand-Name Drugs Bioequivalent Nocebo Effect Efficacy Expectancy Effects Double-Blind Studies Timeline 2/25-3/3 2/26: Physics Exam 3/4-3/10 Spring Break (no school work done) 2/27: Research done in the library. 4/1-4/7 4/2: Research Rough Draft due 4/4: Organic Chemistry 4/8-4/14 4/9: Finish up field research if not completed. 4/11 Research Conference 3/11-3/17 3/13: Research done in the library 3/15: Organic Chemistry Quiz 4/15-4/21 4/16: Finish the final draft of the research paper. 4/18 Research Final Draft 3/18-3/24 3/19: Research done in the library 3/25-3/31 3/21: Annotated Bibliography Rough Draft due 3/26: Annotated Bib Final, Physics Exam Organic Chemistry Exam 3/22-3/24: Miami Trip (no school work done) 4/22-4/28 4/25 Self Assessment and Portfolio Due 3/28: Create survey for field research. 4/29-4/30 4/29: Organic Chemistry Final Physics Final Whitehurst 4 Quiz Draft due due Organic Exam Annotated Bibliography Bobo, W., Stovall, J., Knotsman, M., Koestner, J., & Shelton, R. (2010). Converting from brandname to generic clozapine: A review of effectiveness and tolerability data. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 67(1), 27. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080595 Summary from Abstract: PURPOSE: The effectiveness and tolerability of switching patients' therapy from brand-name to generic clozapine are reviewed. SUMMARY: Clozapine is the most effective treatment for patients with refractory psychotic disorders and is also effective for reducing suicidal and violent behavior in this same population. Generic versions of clozapine are widely used. However, possible differences in pharmacokinetic profiles between branded and generic clozapine, and the potential risks of medication changes in severely ill but stable patients, may result in apprehension about converting from branded to generic clozapine. Articles, abstracts, and clinical presentations that compared clinical outcomes between Clozaril (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ) and generic forms of clozapine in patients with primary psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, or related conditions were identified via a computerized search of the medical literature. Thirteen relevant reports, mostly uncontrolled observational studies or chart reviews, described the effects of switching from brand-name to generic clozapine in 966 patients. The majority of patients tolerated conversion without worsening of symptoms or adverse effects, increased intensive service utilization, or medication adjustment. Clinical deterioration was described in a case review and in one randomized, controlled study. CONCLUSION: Available literature supports the effectiveness and safety of generic clozapine formulations in patients who previously were stable during treatment with brand-name clozapine. The risk of poor outcome after conversion to a generic clozapine formulation appears to be low but difficult to predict. Patients should be closely monitored during the first one to three months after conversion from one formulation to another. The authors seem to be credible as this source is from a peer-reviewed journal. They looked at a large sample size compared to many other studies on the topic of generic and brand-name medications, and they took this sample size from a total of thirteen separate studies. These two factors also add to their credibility and give reason to believe they were unbiased in their research. This article exemplifies the viewpoint that generic drugs are mostly safe but should still be evaluated on a case by case basis. Borgheini, G. (2003). Bioequivalence and other unresolved issues in generic drug substitution. Clinical Therapeutics, 25(6), 1578-92. Summary from Abstract: For the purposes of drug approval, the interchangeability of a generic drug and the corresponding brand-name drug is based on the criterion of “essential similarity,” Whitehurst 5 which requires that the generic drug have the same amount and type of active principle, the same route of administration, and the same therapeutic effectiveness as the original drug, as demonstrated by a bioequivalence study. However, bioequivalence and therapeutic effectiveness are not necessarily the same. Objective: This review summarizes available data comparing the bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of brand-name psychoactive drugs with those of the corresponding generic products. Methods: Relevant information was identified through searches of MEDLINE, Current Contents/Clinical Medicine, and EMBASE for English-language articles and English abstracts of articles in other languages published between 1975 and the present. The search terms used were generic drug, branded drug, safety, toxicity, adverse events, clinical efficacy, bioequivalence, bioavailability, psychoactive drugs, and excipients. Results: Few publications compared the bioequivalence and efficacy of brandname and generic psychoactive drugs. Those that were identified revealed differences in the efficacy and tolerability of brandname and generic psychoactive drugs that had not been noted in the original bioequivalence studies. Specifically, l study found that plasma levels of phenytoin were 31% lower after a switch from a brand-name to a generic product. Several controlled studies of carbamazepine showed a recurrence of convulsions after the shift to a generic formulation. After a sudden recurrence of seizures when generic valproic acid was substituted for the brand-name product, an investigation by the US Food and Drug Administration found a difference in bioavailability between the 2 formulations. Statistically significant differences in pharmacokinetic variables have been reported in favor of brand-name versus generic diazepam (<F>P < 0.001</F>). Finally, a case report involving paroxetine mesylate cast doubt on the tolerability and efficacy of the generic formulation. Conclusion: The essential-similarity requirement should be extended to include more rigorous analyses of tolerability and efficacy in actual patients as well as in healthy subjects. This author conducted research similar to what I am doing now, and his conclusion is similar to my view that more studies need to be performed. It seems he would be unbiased because he was looking at multiple sides of the issue like I am. He also does not come to any unfounded conclusions with his research. Dunckley, V. (2012, March 26). Brand vs. generic: When it matters (and what to do when it does). Psychology Today, Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mentalwealth/201203/brand-vs-generic-when-it-matters-and-what-do-when-it-does This is a magazine article that highlights the dangers of generics and how the FDA is ineffective at evaluating them. It includes information about the antidepressant Wellbutrin and how the author had heard from many individuals that they suffered adverse reactions to the generic version, including thoughts of suicide. He contacted the FDA and they told him to fill out an “adverse event report,” but it seemed to be ineffective in doing anything. He further writes that sources from a manufacturing plant in India in claim generics are nowhere near the same, and that manufacturing of generics is generally questionable. Whitehurst 6 The author is a writer for Psychology Today so I do not believe he would be biased in one direction or another. It seems more likely, based on the magazine the article was published in, that he would want to provide the most accurate information possible since much of his audience would be psychiatrists or clinical psychologists. Gaudiano, B., & Miller, I. (2006). Patients' expectancies, the alliance in pharmacotherapy, and treatment outcomes in bipolar disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 671-76. Summary from Abstract: Bipolar disorder is characterized by a chronic and fluctuating course of illness. Although nonadherence to pharmacotherapy is a frequent problem in the disorder, few studies have systematically explored psychosocial factors related to treatment discontinuation. Previous research with depressed patients receiving psychotherapy has suggested that expectancies for improvement are related to treatment outcomes and that the therapeutic alliance may partially mediate this relationship. The current study found evidence for a similar relationship between patients' initial expectancies for improvement, patient and doctor-rated alliance, and long-term outcomes in bipolar patients treated with pharmacotherapy for up to 28 months following an acute episode. The results highlight the need for the assessment of expectancies and alliance in bipolar treatment and suggest possible targets for psychosocial interventions. This is another source from a peer-reviewed journal, so bias is likely not an issue. This article is not directly related to the topic of generic or brand-name drugs, but it highlights the importance of additional factors such as doctor-patient relationship and expectations in treatment outcomes. Because research entirely related to my topic is limited, this study suggests that the potential harms of generic medications could be avoided by thoroughly explaining them to the patients. History of generic drugs. (2013). Retrieved from http://ipharmacylist.com/meds/history-ofgeneric-drugs.html This internet source tells how the generic drug market came to be, saying that it started with a generic version of Bayer aspirin in the 1920’s. There is no author listed on the website, but it still gives a plethora of information on the history of this market. Regulations have varied in the United States throughout the last 90 years, with the most recent legislation only requiring proof of bioequivalence of the generic drugs. Because there is no credited author, I cannot evaluate bias based on their credibility. However, this is a source for objective historical information, and thus there is likely no bias. Howland, R. H. (2010). Are generic medications safe and effective?. Journal Of Psychosocial Nursing And Mental Health Services, 48(3), 13-16. doi:10.3928/02793695-20100204-01 Whitehurst 7 Summary from Abstract: Because multiple branded, alternative, and generic medications contain the same active ingredient, controversies sometimes arise regarding generic substitution. For patients, physicians, and nurses, the critical issue is whether generic medications are safe and effective. This article addresses the issue with regard to several antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications. There is no consistent evidence that generic substitutes are less safe or less effective than brand-name equivalents. Uncontrolled reports are subject to many confounding factors and biases. Relapses temporally associated with medication switches could be due to the change but are difficult to distinguish from the natural history of the treated condition. Adverse effects temporally associated with medication switches could also be attributable to the change, but they might be explained as a type of "nocebo" effect. Expectancy theory may be used to explain relapses or adverse effects after generic switches. Randomized controlled blinded studies are necessary to evaluate causality; however, such studies typically have not supported uncontrolled reports that the safety or effectiveness of brand-name and generic drugs differ. It is still clinically prudent to monitor a patient whose medication has been switched. R.H. Howland seems to be a very credible source, as he has published multiple research articles on the subject of bioequivalence of brand-name and generic drugs. I do not believe him to be biased because he must have a great deal of knowledge on the subject at this point. Margolese, H. C., Wolf, Y., Desmarais, J., & Beauclair, L. (2010). Loss of response after switching from brand name to generic formulations: Three cases and a discussion of key clinical considerations when switching. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(3), 180-182. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e328337910b Summary from Abstract: Generic formulations of medications are marketed as therapeutically equivalent and less expensive than branded ones. Multiple studies and case reports have described relapses and worsening clinical outcome in patients after a switch from a brand name to a generic medication. Recent studies have shown that generics do not always lead to the expected costs savings, reducing the impetus to proceed with compulsory generic switching. We report on three patients who experienced clinical deterioration after commencing the generic formulation of their previous brand name psychotropic medication. We discuss key clinical differences between original and generic formulations of the same medication. The use of bio equivalence as an indicator of therapeutic and clinical equivalence, the lack of appropriate studies comparing generic and brand name medications and differences in excipients are some of the factors that could explain variation in clinical response between generic and brand name medications. Generic switching should be decided on a case-by-case basis with disclosure of potential consequences to the patient. These authors have all been published in similar research to this, and the fact that they specify they are only looking at case studies somewhat exempts them from bias. Case studies are not Whitehurst 8 meant to be generalized, so their conclusions are limited but this research still gives me examples of instances when switching to generics can be dangerous. Roman, B. (2009). Patients’ attitudes towards generic substitution of oral atypical antipsychotics: A questionnaire-based survey in a hypothetical pharmacy setting. CNS Drugs, 23(8), 693701. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923080-00006 Summary from Abstract: Generic atypical antipsychotics in tablet form differ in name, appearance and packaging from the innovator brand antipsychotics. These differences might cause anxiety, confusion and misperceptions in some ambulant patients with psychoses/schizophrenia, especially if the brand atypical antipsychotic is substituted in the pharmacy without the acknowledgement of the patient and treating psychiatrist. Furthermore, generic substitution of branded oral atypical antipsychotics in the pharmacy might cause nonadherence and potentially lead to suboptimal treatment outcomes if patients perceive the medicines to be clinically different. Objective: To determine the attitudes of patients with psychoses/schizophrenia towards generic substitution of oral atypical antipsychotics in a pharmacy setting. Methods A total of 106 ambulant patients with psychoses/schizophrenia currently taking an oral atypical antipsychotic (risperidone [Risperdal®], olanzapine [Zyprexa®], quetiapine [Seroquel®] or aripiprazole [Abilify®]) were confronted with generic substitution in a hypothetical pharmacy setting. Two conditions were used: one granting patients a short explanation about the substitution, and one without explanation. Patients' attitudes towards the generic substitution were assessed using a combined quantitative and qualitative design. Results Of the respondents, 73% stated that they would be unlikely to take a generic antipsychotic if their pharmacist were to substitute it. Providing patients with a short explanation had a significantly positive effect on their intention to take a generic version; however, overall, the patients' intention to take the generic antipsychotic lay well below a neutral midpoint. Conclusion Patients with psychoses/schizophrenia using atypical antipsychotics in tablet form perceive generic versions of their antipsychotics as being significantly different. This perceived difference lowers their intention of continuing to take the medication, thus possibly jeopardizing treatment outcome. Caution with the generic substitution of atypical antipsychotics in the pharmacy is therefore recommended. Generic substitution should take place only with the knowledge and agreement of the psychiatrist and the patient. The study that Roman performed used two conditions, so bias could only be found in the fact that all of the patients who took part in the study were living in hospitals. This looked at individuals with one of the more serious mental illnesses, which is an important part of looking at generic drug substitution as the effects on these individuals could be the most consequential. Sansone, R., & Sansone, L. (2010). Psychiatric disorders: A global look at facts and figures. Psychiatry, 7(12), 16-9. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3028462/ Whitehurst 9 Summary from Abstract: According to data from Western countries, psychiatric disorders are relatively prevalent. For example, in the United States general population, data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study indicate that about one-quarter of individuals experience a psychiatric disorder in a given year, with lifetime rates at about 50 percent. For both prevalence designations, anxiety disorders are most common. According to data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders, the 12-month and lifetime-prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders among European general populations are 11.5 and 25.9 percent, respectively, with mood and anxiety disorders evidencing approximately equal rates. As expected, in primary care settings, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the United States and Europe is high, with point-prevalence rates varying, but affecting approximately 25 to 30 percent of patients. In primary care settings, the most common psychiatric diagnoses are mood and anxiety disorders as well as somatoform disorders. While no global summary of cost of care is available, the high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders correspond with high expenditures for mental healthcare, as evidenced by a number of sources. Given these latter findings, prevention becomes all the more relevant in terms of cost management. The authors of this study are both psychiatrists and are looking at objective facts and figures, so there is no bias. These statistics help draw attention to the importance of my research, because about half of the United States will have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at some point in their lives. Solomont, E. B. (2008, July 16). Insurers pay doctors to push generic drugs. New York Sun. Retrieved from http://www.nysun.com/business/insurers-pay-doctors-to-push-genericdrugs/81992/ This online newspaper article explains how an insurance company in Rochester, N.Y. was offering doctors higher compensation for increasing the percentage of generic drugs they prescribe to their patients. The article includes quotes from doctors and the American Medical Association about how this kind of deal sets a dangerous precedent for how doctors should be treating their patients. The author is a reporter for this online newspaper, and he had sources on both sides of the issue in this article to reduce bias. For example, Solomont includes sources that claim there should not be regulations on this kind of practice because people need affordable healthcare; conversely, he includes sources that claim trying to switch more patients to generics could be dangerous.